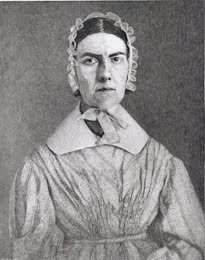

Abolitionist and One of the First Women to Speak in Public in the United States

Angelina Grimke was a political activist, abolitionist and supporter of the women’s rights movement. Her essay An Appeal to the Christian Women of the South (1836) is the only written appeal made by a Southern woman to other Southern women regarding the abolition of slavery. It was received with great acclaim by abolitionists, but was severely criticized by her former Quaker community, and was publicly burned in South Carolina.

Angelina Grimke was a political activist, abolitionist and supporter of the women’s rights movement. Her essay An Appeal to the Christian Women of the South (1836) is the only written appeal made by a Southern woman to other Southern women regarding the abolition of slavery. It was received with great acclaim by abolitionists, but was severely criticized by her former Quaker community, and was publicly burned in South Carolina.

Early Years

Angelina Emily Grimke was born on November 26, 1805, in Charleston, South Carolina, to Mary Smith Grimke and John Faucheraud Grimke, a judge, planter, lawyer, politician and owner of a thriving cotton plantation. The Grimkes were distinguished member of Charleston society, and parents of thirteen children, of which Angelina was the youngest.

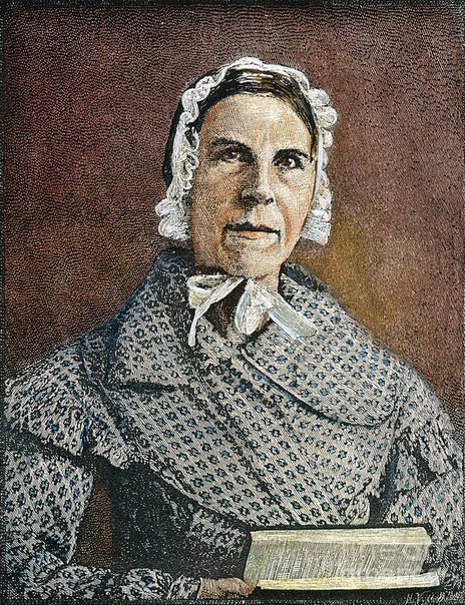

Sarah Moore Grimke was thirteen years old when Angelina was born. Despite their age difference, the sisters were very close and lived together all their lives. Each sister possessed a strong mind and kind soul, and in spite of growing up in a male-dominated southern family, shared the belief that all people are created equal.

The Grimkes lived in two homes: a fashionable townhouse in Charleston and the sprawling Beaufort Plantation in the country. Like other large plantation owners, they kept scores of slaves, who did all the labor at Beaufort, from cotton picking to cooking to caring for the children. Slaves worked as nursemaids to the Grimke children and each was assigned a “constant companion,” a slave child of about the same age who catered to his or her needs.

Sarah saw in Angelina – nicknamed ‘Nina’ – the opportunity to be useful, to be needed. Her mother was worn out from the demands of her huge household and from bearing fourteen children. Sarah begged to become Angelina’s godmother. Her parents agreed, and from that day forward, Sarah assumed a responsibility for her youngest sibling that she would never give up.

Even as a young child, Angelina was described in family letters and diaries as the most self-righteous, curious and self-assured of all her siblings. She seemed to be naturally inquisitive and outspoken, a trait which often offended her traditional family and friends.

As Angelina grew older, she struggled with the issue of slavery. She attended a seminary for daughters of wealthy landowners. One day, a little slave boy was called in to open a window, and Angelina saw that he was covered with whip marks on his legs and back that were still bleeding. In telling the story, Angelina wept. Sarah tried to comfort Angelina but not much could be said; Sarah had learned that she was basically powerless to change conditions in the South.

The Quaker Religion

In 1818, Judge Grimke became very ill, and Sarah went with her father to Philadelphia in search of a cure. The trip opened Sarah’s eyes to life in the North, without slavery, and introduced her to the Quaker religion. Drawn to its antislavery doctrine, Sarah was also attracted to the fact that Quakers allowed women to become leaders within the church; female preachers were common.

When Sarah returned home, after spending nearly a year in the North, she realized she could no longer live in the presence of slavery, even if it meant she had to move away from her family. Within a month of her return and against her mother’s wishes, Sarah packed her bags and moved permanently to Philadelphia, joining the Quaker Society of Friends.

When Sarah left, Angelina became the leader of the Charleston household. With her father deceased and her brothers married or off at school, Angelina was left to look out for her mother and sisters and manage daily operations of the cotton plantation. Angelina begged her mother to free her slaves but her mother saw nothing wrong with keeping slaves.

When Sarah returned to Charleston for a visit in 1827, Angelina was impressed by the simplicity of her sister’s Quaker dress and lifestyle. As Sarah prepared to return to Philadelphia, Angelina also converted to the Quaker religion. But she felt that staying in the South might help persuade other southerners to see the evils of slavery.

The Quaker community was very small in Charleston, and Grimke quickly set out to reform her friends and family. However, she only antagonized those around her by criticizing their love of finery, their idleness, and above all their acceptance of slavery. Perhaps to her surprise, she could not win over her mother or her siblings. “I am much tried at times at the manner in which I am obliged to live here,” she wrote in her journal.

By 1829, she had resolved to live there no longer. In November of that year, she joined Sarah in Philadelphia, and the sisters became active in the Quaker church. While most Philadelphians did not share Angelina’s abolitionist sentiment, she did find a small circle of antislavery advocates. Still, she was uncertain what she could do for the cause of abolition.

Anti-Slavery Work

Meanwhile, antislavery speakers were flooding the East Coast with their messages, which included emancipation, (freedom for the slaves), abolition (the end of slavery altogether) and recolonization (sending the nation’s black population back to Africa).

By 1832, Angelina had become very discouraged by her limited role within the Philadelphia branch of the Quaker church. She longed to be more involved in the slavery issue, and set about to make that happen. She began attending antislavery meetings, encouraged by some male abolitionists’ call to women to become activists in the movement.

In 1835, Angelina was disturbed by violent riots and demonstrations against abolitionists and African Americans in New York and Philadelphia, and by the burning of antislavery pamphlets in her own hometown of Charleston. In his newspaper The Liberator, William Lloyd Garrison appealed to the citizens of Boston to repudiate all mob violence, and she wanted to support his efforts.

Though she had never met Garrison, Angelina wrote him a letter on August 30, 1835, that began:

I can hardly express to thee the deep and solemn interest with which I have viewed the violent proceedings of the last few weeks. This is a cause worth dying for…

Garrison published Angelina’s letter, never thinking to ask permission to share her private thoughts. Her friends among the Quakers in Philadelphia were outraged – Quakers were supposed to receive permission from the church before doing anything on their own. Sarah even asked her sister to withdraw the letter, concerned that the publicity would alienate her from the community.

Though initially embarrassed by the letter’s publication, Angelina refused, and the antislavery community embraced her. Her letter was reprinted in all the major reform newspapers of the day and was printed with Garrison’s Appeal to the Citizens of Boston and the Quaker abolitionist poet John Greenleaf Whittier’s antislavery poem Stanzas for the Time in a widely circulated pamphlet.

Angelina was immediately thrust into the front lines of the fight against slavery. The national recognition as a figure in the abolitionist movement enabled her to participate in many anti-slavery events. In 1836, she and Sarah attended Agents Conventtion of the American Anti-Slavery Society; they were the only women there.

As a result of their new-found friends and activities, the sisters moved to Providence, Rhode Island, to be with a more liberal group of Quakers.

Speaking Out

Angelina and Sarah were invited to speak throughout the Northeast. Angelina proved to be a dynamic and persuasive speaker and was quickly acknowledged as the most powerful female public speaker for the cause of abolition – unequaled by many of the male orators who traveled the reform lecture circuit.

The sisters also spoke out in favor of women working for abolition, saying that throughout the Bible there are examples of women taking public stands on important issues. They addressed Anti-Slavery Society conventions in New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island and Massachusetts and met all the famous abolitionists of the day, including Theodore Weld.

Weld helped polish the sisters’ public-speaking skills and in 1837 they began a twenty-three week lecture tour. Financing the trip themselves, the sisters visited 67 cities, breaking new ground for women as public speakers. It was unheard of for women to address audiences with both men and women and even fewer spoke about the most controversial issues of the day.

What made the Grimkes exceptional was their first-hand experience with slavery and with its daily horrors and injustices. While abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison and Theodore Weld could give stirring speeches about the need to abolish slavery, they could not testify to its impact on African Americans or on their masters from personal knowledge.

While the Grimkes received praise from many for their courageous stand against slavery, they also suffered countless attacks on their character. Because of the controversy their tour created, the sisters became aware of the overwhelming parallels between the role of women and slaves in society. Both were denied the right to vote and the right to a secondary education, and both were treated as second-class citizens.

Angelina’s lectures were critical of Southern slaveholders, but she also argued that Northerners tacitly complied with the status quo by purchasing slave-made products and exploiting slaves through the commercial and economic exchanges they made with slaveowners in the South. Angelina finished the year-long speaking tour with an address to the Massachusetts state legislature, becoming the first woman in U.S. history to speak to a legislative body.

Marriage and Family

After the tour, Angelina was physically exhausted, but she also was in love. On May 14, 1838, she married Theodore Weld in a simple ceremony, with Theodore renouncing all claims to Angelina’s property and Angelina omitting the line “to obey” from her wedding vows. Both black and white Americans attended the ceremony, including William Lloyd Garrison and black schoolteacher and abolitionist Sarah Mapps Douglass.

The Philadelphia Society of Friends expelled Angelina for marrying a non-Quaker and Sarah for attending the wedding. After the wedding (they had one son, Charles Stuart), the sisters spent most of their time assisting Weld with his writing and his political work in Washington. Within the next two years, Theodore, Angelina and Sarah all moved to a farm in New Jersey.

But Angelina and Theodore continued to write, producing American Slavery As It Is in 1839, a documentary account of the evils of the Southern labor system. When Weld, in poor health, retired from the abolitionist movement in 1843, Sarah accompanied the couple to New York and later helped conduct Weld’s interracial school in New Jersey.

Over the next few decades, the Grimke sisters and Weld would earn a modest living as teachers, often in schools that Weld established. They operated a boarding school at Raritan Bay Union, a utopian community, where they taught the children of other noted abolitionists, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

All three kept abreast of political developments and attended antislavery meetings, and Angelina and Sarah remained privately active abolitionists and suffragists. Instead of touring and lecturing, the sisters wrote articles and speeches for others to read at antislavery and women’s rights conventions.

The Grimke Nephews

Henry Grimke, brother of Angelina and Sarah, began a relationship with his house slave Nancy Weston in 1843 that produced three sons, Archibald, Francis and John. Henry planned to move Nancy and his sons to Charleston after the birth of their third child, but he died unexpectedly during the typhoid epidemic of 1852.

A codicil to Henry’s will stipulated that Nancy and his sons become the property of his son, Montague. Henry could not free his family himself because an 1820 state statute prohibited emancipations within the state. Montague allowed Nancy and her sons to live in Charleston relatively free. Later, he made Archibald and Francis slaves in his own household.

It was not until years after Henry’s death that the Grimke sisters learned of their multiracial nephews, after Nancy Weston had also died. Angelina and Sarah arranged to help the boys leave the South and get educations. Archibald and Francis became noted men in their fields of law and religion. In December 1878, Francis married abolitionist and diarist Charlotte Forten.

Civil War Years

During the Civil War, the sisters wrote articles supporting the Union. In March 1863, they penned An Appeal to the Women of the Republic, which urged women to rally to the cause of the Union and hold a convention to support the war effort. Angelina addressed the convention, which was presided over by Lucy Stone, Stanton and Susan B. Anthony.

After the war the sisters and Weld moved to Boston, where they opened a coeducational school and continued to fight for minority rights.

On March 7, 1870, when Angelina was 66 and Sarah was 79, they boldly declared a woman’s right to vote under the Fourteenth Amendment by voting in a local election. Along with forty-two other women, the sisters marched in a driving snowstorm to the polling place. They were jeered by many onlookers, but because of their age, were not arrested. The gesture did not change the law, but received a lot of publicity.

On December 23, 1873, Sarah Grimke died. Angelina suffered several strokes after Sarah’s death, which left her paralyzed for the last six years of her life.

Angelina Grimke Weld died on October 26, 1879. Theodore Weld survived his wife by six years.

All three had lived to see the end of slavery and the rise of a women’s rights movement. In 1863, Angelina wrote: “I want to be identified with the Negro; until he gets his rights, we shall never have ours.”

An Appeal to the Christian Women of the South (1836) is one Angelina Grimke’s most notable works. It is the only written appeal made by a Southern woman to other Southern women regarding the abolition of slavery. The essay also reflects Grimke’s lifelong enthusiasm for universal education for women and slaves. It was received with great acclaim by abolitionists, but was severely criticized by her former Quaker community, and was publicly burned in South Carolina.

A passage from An Appeal to the Christian Women of the South:

Perhaps you have feared the consequences of immediate Emancipation, and been frightened by all those dreadful prophecies of rebellion, bloodshed and murder, which have been uttered. Let no man deceive you, they are the predictions of that same lying spirit which spoke through the four hundred prophets of old… Slavery may produce these horrible scenes if it is continued five years longer, but Emancipation never will.

Angelina Grimke spent her life promoting equality and free speech. She did not seek special treatment for women or African Americans, but simply the equal opportunity to succeed. Her sister Sarah expressed it best when she stated: “All I ask of our brethren is that they will take their feet from off our necks and permit us to stand upright on the ground which God intended us to occupy.”

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Angelina Grimke

Gale Free Resources: Sarah and Angelina Grimke