Women Who Served in the Civil War Cavalry

It is impossible to state with any certainty how many women served as cavalry soldiers in the Union and Confederate armies. The cavalry was considered more glamorous than infantry and artillery, but females who made it in the cavalry had to be excellent horsewomen, in addition to their other soldierly duties. Stories romanticizing their adventurous spirits and extolling their patriotism appeared in the New York Times, the Richmond Examiner and the Chicago Daily Tribune.

Image: Federal Cavalry Charge! at Gettysburg

Is there a cavalrywoman in this painting?

Cavalrywomen

Despite the physical strain, a few women are known to have served in the cavalry branches of both the Union and the Confederate armies. To operate in the field, a cavalry soldier carried her supplies with her: three days’ rations for herself and her horse, about 60 rounds of ammunition, a shelter tent and camping equipment.

In his memoirs, General Philip Sheridan noted that his men discovered two women – a teamster and a cavalry soldier – in his command. While foraging for food in Kentucky, the women became inebriated on some apple cider the found and fell into a river. Sheridan’s men discovered they were women when they pulled them out of the water. Sheridan interviewed the woman the next day. Referring to them as she dragoons, Sheridan wrote:

The East Tennessee woman [the teamster] was found in camp, somewhat the worst for the experiences of the day before, but awaiting her fate contentedly smoking a cob-pipe. [The cavalry soldier] proved to be a rather prepossessing young woman. … How the two got acquainted I never learned, and though they had joined the army independently of each other, yet an intimacy had sprung up between them long before the mishaps of the foraging expedition.

After the battle of Philadelphia, Tennessee (October 20, 1863), two women serving in different Union cavalry units were taken prison. Both were taken to Belle Isle prison in the James River near Richmond, Virginia, still in disguise. One of the women, who had served in the 45th Ohio (Mounted) Infantry, became ill in February 1864. During treatment, her gender was discovered and she was released. The other had served in the 11th Kentucky Cavalry, and she was discovered to be a woman sometime during her imprisonment at Belle Isle.

Malinda Blalock

Union sympathizers Keith and Malinda Blalock were residents of the mountains of western North Carolina, where loyalties were strongly divided. Malinda enlisted in the 26th North Carolina Infantry of the Confederate Army with her husband, taking on the persona of his brother Samuel. This was solely for show – to hide their Union sentiments from Confederate neighbors. They planned to desert and join the Union army as quickly as possible, but that plan fell through. After Malinda was wounded in battle, they returned home.

After living in constant fear of being arrested as deserters and returned to the Confederate Army, Keith and Malinda became outlaws. They rode with other Federal partisans and guerrillas in the Blue Ridge and Great Smoky Mountains of western North Carolina and northeastern Tennessee. They helped Union sympathizers and escaped prisoners navigate the mountains and find safety in the North. Toward the end of the war Keith and Malinda served as scouts and raiders for the 10th Michigan Cavalry, a grueling undertaking in that mountainous region, especially for a woman.

The Blalocks became the most feared marauders of the western North Carolina mountains. Bushwhacking, thieving and murder became their hallmark. Malinda was always by her husband’s side as they made foray after foray into the countryside terrorizing the locals. After the war finally ended, they brazenly took up residence among the Confederate sympathizers they had terrorized during the conflict.

Amy Clarke

One of the most famous Confederate female soldiers was Amy Clarke from Iuka, Mississippi. She served in both cavalry and infantry. At the age of thirty, she enlisted as a private in a cavalry regiment with her husband, Walter, to avoid being separated from him. Using the name Richard Anderson, Clarke fought with her husband until he was killed in Tennessee on April 6, 1862.

Amy grew tired of cavalry life and transferred to the 11th Tennessee Infantry, who met Federal troops in the Battle of Richmond, Kentucky on August 29, 1862. Amy was wounded and taken prisoner by the Union Army. While treating her wound, Union medical personnel discovered that she was a woman, and then transported her to the prison at Cairo, Illinois.

The Jackson Mississippian dated December 30, 1862 reported that Amy had personally buried her husband on the battlefield. She continued to fight in until she was wounded twice, once in the ankle, and then in the breast:

Among the strange, heroic and self-sacrificing acts of woman in this struggle for our independence, we have heard of none which exceeds the bravery displayed and hardships endured by the subject of this notice, Mrs. Amy Clarke. Mrs. Clarke vounteered with her husband as a private, fought through the battles of Shiloh, where Mr. Clarke was killed – she performing the rites of burial with her own hands.

She then continued with Bragg’s army in Kentucky, fighting in the ranks as a common soldier, until she was twice wounded – once in the ankle and then in the breast, when she fell a prisoner into the hands of the Yankees. Her sex was discovered by the Federals, and she was regularly paroled as a prisoner of war, but they did not permit her to return until she had donned female apparel. Mrs. C. was in our city on Sunday last, en route for Bragg’s command.

In August 1863 Clarke was seen at Turner’s Station, Tennessee with lieutenant’s bars on her uniform. Her reputation had succeeded her. A Texas cavalry soldier recognized her as the heroic Amy Clarke, causing quite a sensation among the soldiers.

Mary and Mollie Bell

Two young cousins, Mary and Mollie Bell, grew up on a farm in the mountains of southwestern Virginia. There they learned to ride horses, hunt and scavenge for food. While helping to provide for their family, they became accustomed to hard work.

In the fall of 1862, the uncle who raised the girls became convinced that the Confederacy would lose the war and decided he was leaving home to join the Union Army. The cousins felt a great deal of love and patriotism for their homeland and were infuriated by their uncle’s actions.

Image: Reenactors of J.E.B. Stuart’s Cavalry

Is that a cavalrywoman in the brown hat on the left?

To compensate for their uncle’s disloyalty, twenty-two-year-old Mollie, the more passionate of the two, devised a plan to enlist in the Confederate Army and convinced fifteen-year-old Mary to go with her. They cut their hair, concealed their feminine curves by wearing thick wool shirts, and practiced speaking and walking like men. They each chose a man’s name: Mollie enlisted as Bob Morgan, Mary as Tom Parker. The girls had no problem getting assigned to the Confederate cavalry corps because they furnished their horses and had excellent riding skills.

To compensate for their uncle’s disloyalty, twenty-two-year-old Mollie, the more passionate of the two, devised a plan to enlist in the Confederate Army and convinced fifteen-year-old Mary to go with her. They cut their hair, concealed their feminine curves by wearing thick wool shirts, and practiced speaking and walking like men. They each chose a man’s name: Mollie enlisted as Bob Morgan, Mary as Tom Parker. The girls had no problem getting assigned to the Confederate cavalry corps because they furnished their horses and had excellent riding skills.

The Bells fought in the Shenandoah Valley and in several key battles, including Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, and at Spotsylvania Court House. Both young women were commended for their bravery and their fighting skills. They hid their gender from their fellow soldiers and officers for two years before being discovered. This excerpt from an article in the Richmond Daily Dispatch dated October 31, 1864, explains how they hid their identity for so long:

From the time these girls entered the service up to the day of the fight which took place between [General Jubal] Early and [General Philip] Sheridan on the 19th instant [Battle of Cedar Creek], the secret of their sex was only known to the captain of the company to which they belonged. At this battle he was taken prisoner, and they then, finding it necessary to have some protector, bonded their secret to the commanding officer of the company; but … he reported it to General Early himself, who entered them to be taken to Richmond.

Confederate authorities imprisoned Mary and Mollie at Castle Thunder in Richmond. They were accused of being camp followers or prostitutes, but their fellow soldiers vouched for their bravery and dedication to the Confederate cause.

Committed to Castle Thunder was the headline of the Richmond Sentinel of October 31, 1864:

Mary and Mollie Bell, two girls of eighteen or twenty, who for two years have been serving in Early’s army under the aliases of Tom Parker and Bob Morgan, were, their sex having been discovered, sent to this city in custody Friday night. They were committed to the Castle until further inquiry could be made about them and some other disposition made of them.

Authorities filed no charges against Mary, age seventeen, and Mollie, age twenty-four.

After three weeks, Confederate officials had filed no charges against Mary, age seventeen, and Mollie, now twenty-four; within a few days they released the Bells from prison and sent them home. The headline of the Richmond Examiner of November 25, 1864 read Sending Home the Petticoat Soldiers:

Mollie Bell and Mary Bell, alias Tom and Bob, who were found in General Early’s ranks unfoxing themselves in Confederate grey, have been released from the Castle and sent home to their fond parents in Pulaski county, Virginia. They wore away the same toggery they came in, and seemed perfectly disconsolate at the idea of being separated from their male companions in arms.

Mary Livermore, an agent for the U.S. Sanitary Commission, wrote in 1888:

Someone has stated the number of women soldiers known to the service as little less than four hundred. I cannot vouch for the correctness of this estimate, but I am convinced that a larger number of women disguised themselves and enlisted in the service, for one cause or other, than was dreamed of. Entrenched in secrecy, and regarded as men, they were sometimes revealed as women, by accident or casualty. Some startling histories of these military women were current in the gossip of army life.

It is difficult to understand how so many women were able to join the army. Part of the reason might have been that, as the war progressed, there was a great demand for new recruits. The armies were increasingly depleted by sickness and thousands of deaths on bloody battlefields; recruiting officers might not have been as careful as they were earlier in the war. Also, if a woman waited nearby while a surgeon examined a male friend or relative, she could then take his papers and assume his identity or become his substitute in the army.

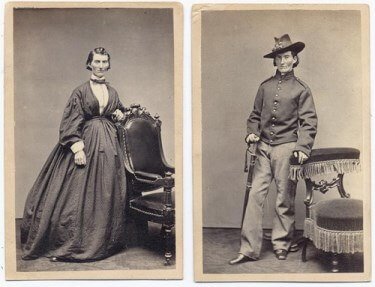

Image: Susannah Smith, 2nd Maine Cavalry

Image: Susannah Smith, 2nd Maine Cavalry

This photograph of a woman in uniform was discovered in a collection belonging to members of the 2nd Maine Cavalry Regiment. The young woman has been identified as Susannah Smith. The 2nd Maine spent most of the Civil War at Barrancas Post near Pensacola, Florida in the District of West Florida, and suffered its heaviest casualties during the Battle of Marianna on September 27, 1864.

Some women who joined the cavalry wanted to experience the freedom that came with living as a man. One female soldier admitted to the Missouri Democrat that her “impulse to shoulder a musket” came from a desire to escape the “monotony of a woman’s life.” That these women were so willing to risk injury, illness or death tells us how eager they were to escape the boredom of their lives at home, knowing this might be their one chance of a lifetime.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Mary and Mollie Bell

Richard Hall: Women in the Civil War

Women soldiers fought, bled and died in the Civil War, then were forgotten