Fredericksburg: City of Hospitals

Image: Fredericksburg during the Civil War

Prior to the Civil War, Fredericksburg, Virginia was a town of approximately 5000 residents. After the War began, it became important primarily because it was located midway between the Union and Confederate capitals: Washington and Richmond.

In early December 1862, during the initial stages of the Battle of Fredericksburg, the town’s civilians were in a quandary. Should they stay or should they go? Many were reluctant to leave their town at the mercy of Union soldiers, horses and war materiel.

But as Union troops crossed the river into the town and serious firing began, many townspeople became refugees, fleeing into the countryside of Spotsylvania County. They took shelter in churches and other public buildings. Or wherever relatives, friends, or perfect strangers, would take them in. A refugee camp was set up on the outskirts of town, but it was soon filled to overflowing.

December 1862: Battle of Fredericksburg

The Battle of Fredericksburg (December 11–15, 1862) was fought by CSA General Robert E. Lee‘s Army of Northern Virginia and the Army of the Potomac, commanded by USA General Ambrose Burnside. As the generals sparred and parried, the remaining civilians fled by the thousands. And it was bitterly cold. Less than two weeks before Christmas.

On December 13, USA General William Franklin’s division pierced the first defensive line of CSA General Stonewall Jackson to the south, but was finally repulsed. Union troops then assaulted Confederate defenses on the high ground above the town, known as Marye’s Heights. General Burnside ordered repeated frontal attacks against Confederates behind a stone wall, all of which were repulsed with heavy losses. On December 15, Burnside withdrew his army, ending the campaign.

Image: Courage in Blue by Mort Kunstler

During the Battle of Fredericksburg, Northern troops repeatedly assaulted heavily-fortified Southern positions on Marye’s Heights – and were slaughtered.

The South celebrated their great victory with joy; while in the North, the Army and President Lincoln came under strong attacks from politicians and the press. Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin visited the White House after a trip to the battlefield. He told the president, “It was not a battle, it was a butchery.” Curtin reported that the president was “heart-broken at the recital, and soon reached a state of nervous excitement…” Lincoln wrote:

“If there is a worse place than hell, I am in it.”

During the battle, buildings and homes in the town were damaged by the Union bombardment and looting by Northern troops. Despite the overwhelming Confederate victory, Fredericksburg would ultimately fall to the Union Army only five months later.

May 1864: Grant’s Overland Campaign

Between May 4 and May 20, 1864, the CS Army of Northern Virginia and the US Army of the Potomac, with its new commander General Ulysses S. Grant, were involved in one continuous battle. The fighting began at the Wilderness, the same area where the Battle of Chancellorsville was fought a year earlier, and progressed along a country lane to the sparsely populated crossroads a few miles west at the Spotsylvania Court House.

The Union suffered casualties more than twice as heavy as those of the Confederacy: an astounding loss of 18,000 men during the few days of fighting at the Wilderness and another 18,000 during the two-week battle at Spotsylvania Court House. This compares to a total loss by the Confederates of only 18,000 for both battles.

A City of Hospitals

A massive number of injured soldiers – estimated at 26,000 wounded and dying men – descended upon the town after the Battles of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania Court House. The Wilderness was fought in the same area as the Battle of Chancellorsville (May 1863), and Spotsylvania Court House was about 11 miles southwest of Fredericksburg.

The first wagon train of wounded arrived in the city on May 9, and they kept coming as the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House waged for almost two weeks. From then until May 26, 1864, more than 26,000 wounded Union soldiers flooded the town after the Union army designated Fredericksburg as its evacuation hospital. One reporter wrote:

Hourly, as the days and nights slipped on, trains of ambulances from the distant field wound along the streets, pausing here and there to leave additional wounded, or to permit the guards to lift out the dead and dying, and carry them away on stretchers to the dead-house, or the rooms where the more serious cases were attended to by the surgeons. Scarcely an hour passed, in the five days immediately following our arrival, that trains of this kind did not reach the town.

As many as 500 civilian relief workers came to Fredericksburg to help care for the wounded, about 30 of whom were women. This group included names now familiar to historians and the public: Julia Wheelock, Arabella Griffith Barlow (wife of General Francis Barlow), Cornelia Hancock, Helen Gilson, and Jane Grey Swisshelm, an independent woman who published her own newspaper in Minnesota.

Eyewitnesses described the scene as wounded soldiers and their caretakers took over virtually every home and building in the small town. Caring for that many wounded was a monumental human accomplishment of enormous proportions, especially considering the lack of medical knowledge and equipment. But the patients did not linger; as soon as they were well enough, they were transported to military hospitals in the North. Only the most serious cases remained longer.

Abigail Hopper Gibbons

Gibbons was an active abolitionist, a conductor on the Underground Railroad, and an ardent supporter of the Union war effort. After the war began, she and her daughter Sarah Hopper Gibbons Emerson, recently widowed, volunteered as nurses. They spent fifteen months working at the military prison at Point Lookout, Maryland in 1862 and 1863.

Image: Nurses and Officers of the U.S. Sanitary Commission

Seated: Abigail Hopper Gibbons and her daughter Sarah in the hat

Fredericksburg, Virginia, May 1864

In May 1864 the two Gibbons women answered the call for volunteers at Fredericksburg. At age 62, Abigail Hopper Gibbons was probably the oldest female volunteer. Mother and daughter arrived on May 19, 1864, and would remain for a week. Abigail wrote:

… Started for this place 7:30 a.m., wading through mud to get to the ambulances. Such a road! [the road from Belle Plain to Fredericksburg] and how wounded men ever bear the transportation is a mystery. Twelve miles of jolting which took seven hours and tired us nearly out! …

Reached Fredericksburg at 2 P.M. Had dinner and I was put into a Hospital at once. The whole town is filled with wounded. House after house, store after store, filled with men lying on the floor. I have about 160. We see nothing but frightfully wounded men.

This is an excerpt of a letter written by Sarah Hopper Gibbons Emerson a few days later:

You can form no idea of the work we had to do in Fredericksburg. I had a hundred and sixty men, all on the floor and not a bed to be seen; four storehouses and one third story, packed so close that the men nearly touched each other; in one room with twenty-three men, fourteen amputations ; not a breath of air until Mr. Thaxter knocked out the windowpanes and afterwards the sashes. We stole straw to fill ticks, stole boards to make bunks, stole bedsteads, took nails from packing boxes, and yesterday every man was comparatively comfortable. The filth exceeded anything you ever dreamed of – stench terrific. The Sanitary Commission has been the only decent feature of the place. Some of the Christian Commission have worked splendidly too. The Sanitary agents washed men, dressed wounds, and did everything. They have saved hundreds of lives, for provisions were terribly scarce and nothing was to be had in the city. I think it was Sunday morning, the report was that 23,000 wounded had been sent on, 7,166 remained, besides 1000 sick.

Georgeanna Woolsey

Georgeanna Georgy Woolsey was one of the Woolsey sisters, members of a socially conscious family from New York. All of the sisters became involved in nursing or relief work during the war. Abby Howland Woolsey, Jane Stuart Woolsey, Mary Woolsey Howland and Eliza Woolsey Howland all spent time caring for Union soldiers. Georgy recorded her experiences at Fredericksburg in letters to family members.

Georgeanna Woolsey letter to her sister:

Fredericksburg, May 19.

…Men are brought in and stowed away in filthy places called distributing stations. I have good men as assistants, and can have more. We go about and feed them; I have a room of special cases, besides the station; three of these died last night. They had been several days on the field after being shot, in and out of the rebels’ hands, taken and retaken. The townspeople refuse to sell or give, and we steal everything we can lay our hands on, for the patients; more straw-stealing, plank-stealing, corn-shuck-stealing; more grateful, suffering, patient men.May 22.

No confusion was ever greater. Tent hospitals have been put up, and the surgeons ordered not to fill them. Orders came from Washington that the railroad should be repaired, then orders came withdrawing the guard from the road. Medical officers refuse to send wounded over an unguarded road. Telegram from Washington that wounded should go by boat. Telegram back that wounded were already over the pontoons, ready to go by rail if protected. Telegram again that they should go by boat. Trains came back to boat, river falling.One boat got painfully off; second boat off; ambulance trains at many hospital doors; got on train and fed some poor fellows with egg nog; moved on with the slow moving procession; at every moment a jolt and a “God have mercy on men,” through the darkness over the pontoons to the railroad, again! I cooked and served to-day 936 rations of farina, tea, coffee, and good rich soup, chicken, turkey, and beef, out of those blessed cans…

We are lodged with a fine old lady, mild and good, in a garden full of roses. We board ourselves. We have crackers, sometimes soft bread, sometimes beef. Last night we had a slice of ham all round. The town will be deserted in a few days. We are sweeping and cleaning Mrs. –‘s rooms to leave the old lady as well off as we can, for all her slaves have packed their feather-beds and frying-pans, and declare they will go with us.

Georgeanna joined the U.S. Sanitary Commission Hospital Transport Service, hospital ships that transported sick and wounded soldiers from the front to Northern military hospitals. She served throughout the war, working in the field following several battles, including Chancellorsville, Gettysburg and battles of Grant’s Overland Campaign.

Washington Woolen Mill

The Washington Woolen Mill stood about a quarter-mile above the town. When the Civil War began, the mill was completely new and it employed 35 female workers, the largest employer of women in Fredericksburg. During the first Union occupation in the summer of 1862, the Union army turned the mill into a hospital. The mill served as the hospital for men of the Fifth Corps during the Wilderness and Spotsylvania.

A Confederate Hospital at Fredericksburg

June 1861: Alexander and Gibbs Tobacco Factory

By late June 1861, a hospital for approximately 150 Confederate soldiers who were sick from disease was established at the Alexander and Gibbs Tobacco Factory in Fredericksburg. A tobacco factory would seem an unlikely place for a military hospital, but at the time there were few other options. The Union army had already taken over public buildings, shops, homes and the courthouse.

Betty Herndon Maury wrote in her diary June 26, 1861:

The sick suffer a great deal for want of proper medical attendance and good nursing. Many of the soldiers are laid on the floor when brought in, and are not touched, or their cases looked into, for twenty-four hours. One or two died when no one was near them; they were found cold and stiff several hours afterwards. The other night at ten o’clock, when one of the ladies left, there was not a soul in the house besides the sick men. Every one in town has been interested in them.

Two days later, the Fredericksburg News reported:

The Ladies of Fredericksburg have organized a regular system for attending to the sick soldiers of our Hospital. Six ladies are in attendance constantly, whose office it is to superintend in various departments, and it is earnestly recommended to all who are desirous of aiding in this good work to act in connection with the committee of six ladies who will always be found in attendance.

Apparently that system did not work for long. Soon after, the female Confederate humanitarians in town decided that a much more expedient solution was to simply take the sick soldiers into their homes.

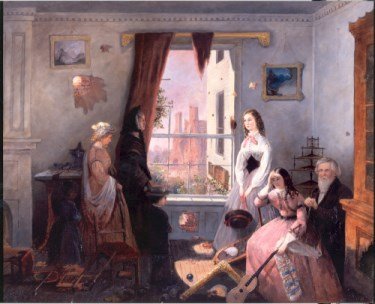

Image: Return to Fredericksburg After the Battle

Image: Return to Fredericksburg After the Battle

By David English Henderson

Union soldiers were moved from field hospitals to permanent hospitals in Washington DC as soon as possible. The general rule was to transport them as soon as they were healthy enough to make the trip and transportation became available. On May 27, 1864, orders were given to evacuate Fredericksburg. Within two days, all wounded soldiers and Union officials had left town.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Battle of Fredericksburg

Mysteries and Conundrums: Exploring William Street

Abby Hopper Gibbons: Abolitionist and Civil War Nurse

Mysteries and Conundrums: Who’s the woman in the pictures?