Caring for the Wounded in Our Nation’s Capital

Federal General Hospitals

Federal General Hospitals

The title of United States Army General Hospital applied to facilities where soldiers from any military unit, unlike Division or Corps Hospitals.

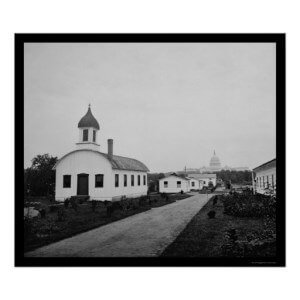

Image: Harewood Hospital

Washington DC

From 1861 through 1865, General Hospitals treated more than one million soldiers with a mortality rate of only eight percent, the lowest ever recorded for military hospitals and better than many civilian facilities. Washington’s sixteen General Hospitals comprised nearly 30,000 beds.

Harewood General Hospital

In 1852 financier William Wilson Corcoran purchased 191 acres to use as a country estate east of the Seventh Street Turnpike and north of what is now McMillan Reservoir. In 1862 Harewood Hospital was built on Corcoran’s property in a “V” pavilion style. It operated between September 1862 and May 1866, caring for wounded soldiers who arrived in caravans of horse-drawn ambulances.

Harewood consisted of frame buildings and tents, some without heat or ventilation. A few existing buildings – wooden barracks and a brick farm house – were incorporated into the hospital, which consisted of nine wards, with 63 beds each, for a total of 945 beds. To these were added hospital tents with six beds each. At one point, 312 hospital tents were in use on the site, with a capacity of 1,872 beds. In December 1864, the hospital had 2,080 beds. It was the last of Washington’s Civil War hospitals to close.

Judiciary Square General Hospital

Between 1861-1862, the U.S. Sanitary Commission urged the government to build pavilion-style hospitals, instead of renting buildings ill-adapted for hospitals. As a result, Armory Square, Mount Pleasant, and Judiciary Square hospitals were completed 1862. These state-of-the-art hospitals featured separate wards, or pavilions, radiating from a central corridor. They were based on the British design first used in the Crimean War and emphasized ample ventilation.

Washington was often inundated with casualties from the Army of the Potomac. Historian Charles Bracelen Flood wrote:

Steamboats with names like Lizzie Baker, Connecticut, and General Hooker, their whistles blaring in harsh ghostly tones, landed at the Sixth Street wharves in downtown Washinngton, where long lines of horsedrawn ambulances waited to take the wounded to Washington’s twenty-one overcrowded hospitals.”

Mary Clemmer Ames, a Washington resident during the Civil War, wrote:

Arid hill, and sodden plain showed alike the horrid trail of war. Forts bristled above every hill-top. Soldiers were entrenched at every gate-way. Shed hospitals covered acres on acres in every suburb. Churches, art-halls and private mansions were filled with the wounded and dying of the American armies. The endless roll of the army wagon seemed never still. The rattle of the anguish-laden ambulance, the piercing cries of the sufferers … made morning, noon and night too dreadful to be borne.

Douglas General Hospital

Sisters of Mercy took over operation of Washington Infirmary in 1855. When the Civil War began in 1861, they offered the Infirmary to the government. When it burned down later that year, the government seized the private mansions of Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, Vice President John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky and Senator Henry Rice of Minnesota

These dwellings the Douglas General Hospital.

The War Department asked the sisters to take charge of Douglas Hospital on December 23, 1861. Former superior at the Infirmary, Sister Mary Colette O’Connor served as superintendent. She possessed remarkable executive abilities and a tender heart. Unfortunately her health was weakened by the grueling work, and Sister Mary Colette died July 16, 1864.

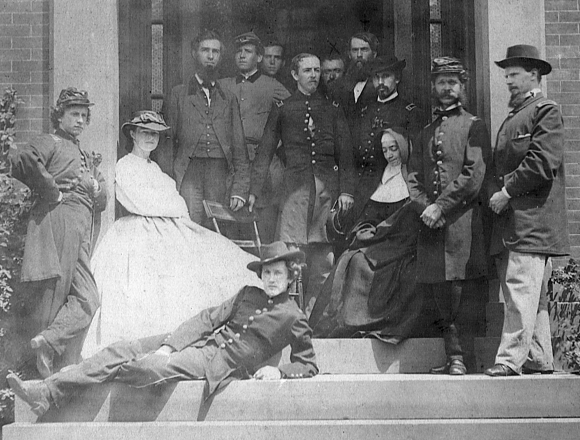

Sister Mary Collette O’Connor on the front steps of Douglas Hospital with military and staff

The Sisters of Mercy compassionately cared for the sick at Douglas and prepared the dying for eternity. More than six hundred Catholic sisters served during the Civil War and a hundred of these were Sisters of Mercy. The only organized, experienced, and available nurses in the country, they nursed the wounded; organized housekeeping, cooking, and distributing food; and providing laundry services. They often risked death by tending to patients with contagious diseases.

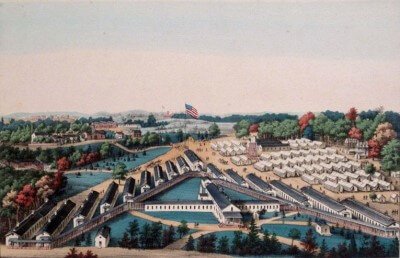

Pavilion-Style Hospitals

The large pavilion-style hospitals constructed during the war comprised a hundred or more independent wooden barracks that were well ventilated and could be easily isolated in case of disease outbreak or fire. The hospitals bought food locally and grew vegetables in gardens at the facilities. Ample supplies of fresh water and herds of dairy cows contributed to the welfare of the patients; some hospitals had their own icehouses and breweries.

Many patients recovered from their injury or disease because they were removed from an environment that was contributing to their illness. Some of pavilion-style facilities had mosquito netting installed above the patients’ beds, but they were little used because they were confining and hot.

Journalist Noah Brooks observed in 1864:

All Washington [is] a great hospital for the wounded in the great battle now going forward in Virginia. Boatloads of unfortunate and maimed men are continually arriving at the wharves and are transported to the various hospitals in and around Washington in ambulances or upon stretchers, some of the more severely wounded being unable to bear the jolting of the ambulances. … There are twenty-one hospitals in this city and vicinity and every one of them is full of the wounded and the dying.

Campbell General Hospital

Originally designed as a barracks for cavalry, the buildings at Florida Avenue and Sixth Street were converted into Campbell Hospital to care for a steady stream of wounded. It consisted of long, low, one-story buildings made of rough boards. These structures served primarily as wards, but the center building housed a dining room and kitchen. Eleven wards comprised six hundred beds. The Medical Department installed ridge ventilation in which the earth was cleared away from the walls during summer for air movement. Louvered exits were used in winter with inlets near the stoves.

Many converted barracks hospitals were not connected to the municipal water supply; Campbell Hospital was more fortunate due to its location. Water from the Potomac River was distributed to the wards. Waste water was carried off by drains to sewers and every other ward had a bathroom and sinks that were kept clean by a running stream.

Ambulance Corps

Transporting the wounded from battlefields to these hospitals were another challenge. Wounded soldiers were roughly placed into rickety two-wheeled vehicles which jostled and bumped along rugged paths and rutted roads. The injured were sometimes fortunate to be taken off the battlefield at all; ambulance drivers sometimes fled at the first sound of gunfire nearby.

One surgeon described the drivers as

“the most vulgar, ignorant, and profane men I ever came in contact with … such as would disgrace … any menials ever sent out to the aid of the sick and wounded.”

They ignored the cries of their patients and had not even the decency to get water for the wounded during the short stops on the journey.

Army of the Potomac medical director Jonathan Letterman developed the Letterman Ambulance Plan, in which there were two stretcher-bearers and one driver per ambulance. It was their job to collect the wounded from the battleground, bring them to the dressing stations, and then carry them to the field hospitals.

This plan was a vast improvement in the evacuation of the wounded from the battlefield, but Congress did not publish the act that created an Ambulance Corps for all Union Armies until March 1864.

Carver General Hospital

Carver Hospital stood on Meridian Hill, near Colombian College. Originally built as Army barracks, the buildings were converted into hospitals after their regiments departed for the battlefront.

Poet Walt Whitman arrived in Washington in late December 1862, and he “made over six hundred visits or tours, and went, as I estimate, counting all, among from eighty thousand to a hundred thousand of the wounded and sick.” Those that Whitman knew best were the barracks style hospitals, like Campbell and Carver, which he called, “a wall’d and military city regularly laid out, and guarded by squads of sentries.” Whitman wrote:

I do not see that I do much good to these wounded and dying; but I cannot leave them. Once in a while some youngster holds on to me convulsively, and I do what I can for him; at any rate, stop with him and sit near him for hours, if he wishes it.

The President and First Lady Visited DC Hospitals

Military hospitals, including Harewood, Columbia College, Carver, and Mount Pleasant hospitals were located on the outskirts of the city, near President Lincoln’s summer cottage at the Soldiers’ Home. Both President and Mrs. Lincoln frequently visited these hospitals to offer comfort to the soldiers, who cheered when the president arrived. The President passed Harewood Hospital on his commute between his summer retreat and the White House, and he sometimes stopped there for a visit.

According to this excerpt from Lincoln’s Men by William Davis, President Lincoln enjoyed visiting soldiers in military hospitals:

Unannounced, he might simply appear in a ward to talk with the men in their cots. “I can’t stay, boys,” he said in one hospital where he rapidly went from ward to ward. “I hope you are all comfortable and getting along nicely here.” When time allowed, he went to each bed, shaking hands with every soldier in turn. What he saw often left him shocked and horrified. His friend and companion [Ward Hill Lamon] sometimes saw the president disturbed “almost beyond his capacity to control either his judgment or his feelings.”

On March 17, 1865, John Wilkes Booth learned that President Lincoln planned to visit wounded soldiers at Campbell General Hospital and attend a performance of the play, Still Waters Run Deep, in the theater there. Historian Robert H. Fowler wrote:

With an hour’s notice, according to John Surratt, the gang raced out, waited until they saw a carriage approach. Riding alongside, they saw the man in the vehicle was not Lincoln. It may have been Salmon P. Chase, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, who did attend the show.

President Lincoln had changed his schedule, thus postponing his assassination for nearly a month.

SOURCES

“I Cannot Leave Them”

Mount Pleasant History

Washington’s Civil War Hospitals

The War Effort: Campbell General Hospital

Civil War Sisters Healing the Wounds of the Nation