Women Who Fought in the Civil War

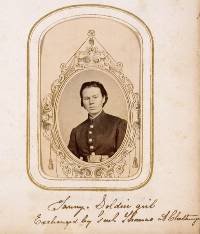

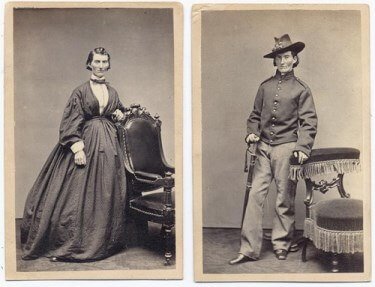

They were determined to fight, no matter the cost. They dressed in men’s clothing and assumed masculine names; bound their breasts; rubbed dirt on their faces to simulate whiskers; learned to talk, walk, chew and smoke like men; and hid in every conceivable way that they were female. They were soldiers in the Civil War.

They were determined to fight, no matter the cost. They dressed in men’s clothing and assumed masculine names; bound their breasts; rubbed dirt on their faces to simulate whiskers; learned to talk, walk, chew and smoke like men; and hid in every conceivable way that they were female. They were soldiers in the Civil War.

Both the Union and Confederate Armies forbade the enlistment of women, but historians have estimated that some 400 women went to war (there were probably more), some without anyone ever discovering their gender. Because they passed as men, it is impossible to judge how many women soldiers served in the Civil War. Some joined the army out of loyalty to their cause, some for the adventure, while poverty pushed others to join for a soldier’s meager pay.

The existence of female soldiers was no secret during or after the Civil War. The reading public was well aware that these women rejected the social constraints that confined them to the domestic sphere. The motives of these women were perhaps open to speculation, but not their actions, as numerous newspaper stories and obituaries of women in uniform testified.

No Union Women Soldiers?

Despite recorded evidence to the contrary, the Adjutant General of the U.S. Army tried to deny that women played any military role in the Civil War. On October 21, 1909, Ida Tarbell of The American Magazine wrote to Adjutant General F. C. Ainsworth:

I am anxious to know whether your department has any record of the number of women who enlisted and served in the Civil War, or has it any record of any women who were in the service?

She received a swift reply from the Records and Pension Office, a division of the Adjutant General’s Office (AGO), under Ainsworth’s signature, which read in part:

I have the honor to inform you that no official record has been found in the War Department showing specifically that any woman was ever enlisted in the military service of the United States as a member of any organization of the Regular or Volunteer Army at any time during the period of the Civil War. It is possible, however, that there may have been a few instances of women having served as soldiers for a short time without their sex having been detected, but no record of such cases is known to exist in the official files.

This response to Ms. Tarbell’s request is a blatant lie. One of the duties of the AGO was maintenance of the U.S. Army’s archives, and they carefully preserved all records created during the War. By 1909 they had also compiled military service records (CMSRs) for all participants, both Union and Confederate, by painstakingly copying names and remarks from official federal documents and captured Confederate records.

At least one CMSR proved that the army did have documentation of the service of women soldiers. Mary Scaberry, alias Charles Freeman, enlisted as a private in the Fifty-second Ohio Infantry in the summer of 1862 at the age of seventeen. On November 7 she was admitted to the General Hospital in Lebanon, Kentucky, suffering from fever, and was transferred three days later to a hospital in Louisville, where hospital personnel discovered her ‘sexual incompatibility,’ and discharged her from Union service.

This is an excerpt from a pamphlet entitled ‘Women Warriors’ by Daniel Livermore – whose wife, women’s rights advocate Mary Livermore, served as a Union nurse:

While the number of women who listed in the Union army is not large, still, they are sufficiently numerous to answer the objection which many make against the fighting ability of woman. All history shows that she can fight in defense of her rights and for the honor of her country. Women are patriotic and self-sacrificing and are abundantly able to enforce their wills and defend their votes. And therefore, this objection of woman’s inability to fight and to defend her right to the franchise falls to the ground, as does every objection to woman suffrage when carefully examined.

Not so Famous Women Soldiers

We have all read about the well known women who served as Civil War soldiers, but there are hundreds of others who have received little or no recognition. Some women simply could not tolerate being separated from family members; others would have faced a life of poverty and hardship if left at home without male support – a common problem with so few jobs open to women.

Martha Parks Lindley enlisted just two days after her husband left home to serve in the 6th U.S. Cavalry. “I was frightened half to death,” she told a newspaper. “But I was so anxious to be with my husband that I resolved to see the thing through if it killed me.” It did not, and fellow troopers simply assumed that Mr. Lindley and the ‘young man’ known as Jim Smith were just good friends.

Bridget Devens

Joining the First Michigan Calvary along with her husband, Bridget Devens (Divers or Deavers) – often called Michigan Bridget – spent much of her time behind the front lines tending the wounded. However, author Mary Livermore wrote: “Sometimes when a soldier fell, she [Devens] took his place, fighting in his stead with unquailing [determined] courage. Sometimes she rallied the troops – sometimes she brought off the wounded from the field – always fearless and daring, always doing good service as a soldier.”

Bridget’s actual combat experience probably ended in 1864 when General Ulysses S. Grant banished all women from military operations. She subsequently worked with the United States Sanitary Commission. Most of her time during the last year of the war was spent in the Cavalry Corps Hospital at City Point, Virginia, where she cared for wounded soldiers and was a tentmate of Cornelia Hancock, a famous Quaker hospital worker for the Union cause.

Mary Owens

Some female combatants were given away by ladylike mannerisms, but most were unveiled only when doctors stripped away their clothes to examine a war wound. Mary Owens’ affection for her fiance William Evans was so intense that, over her father’s objection, they eloped. Mary disguised herself as William’s brother John, and they enlisted in the 9th Cavalry shortly after the war began.

The couple fought courageously side by side until William was killed in action. Mary Owens, aka John Evans, tenaciously soldiered on until she was seriously wounded and her gender was discovered, ending an 18-month military career that spanned three major battles. She had mastered being a man.

Mollie Bean

The Richmond Whig printed an article on February 20, 1865 about a young woman who was captured in Virginia on February 17:

A young woman, dressed in military uniform, was arrested somewhere up the Danville Railroad and sent to this city, charged with being a suspicious character. On examination of the Provost Marshal’s office it appeared that her name was Mollie Bean, and that she had been serving in the 47th North Carolina Regiment for over two years, during which time she had been twice wounded. She was sent to Castle Thunder, that common receptacle of the guilty, the suspected, and the unfortunate. This poor creature is, from her record, manifestly crazy. It will not, we presume, be pretended that she had served so long in the army without her sex being discovered.

The Richmond Sentinel and the Richmond Enquirer also ran the story. A North Carolina newspaper, the Charlotte Daily Bulletin, ran a longer version of the story on March 2:

The train guard on the Danville cars encountered a delicate looking individual, decked out in a Yankee great coat, and a pair of light colored pants, and a jaunty little fatigue cap, stuck rakishly on the head, one side resting close against the right ear. As the face was a strange one, the guard demanded ‘Your papers, sir,’ to which the individual in the great coat responded, ‘I’ve got no papers, and damn if I want any.”

To attempt to travel on the cars without papers signed by the Provost Marshal and all his assistants, and from the commandant of conscripts and all his clerks, is downright treason in the eyes of any detective, and so the delicate individual in the great coat and corduroy pants was ejected vict armis [?], placed in the hands of another officer, and marched off to the office of chief of police.

Here the strange individual was subjected to the most rigid cross questioning, and much to the astonishment of all, it was ascertained that the great coat encompassed the form of a female… She states that she was twice wounded in battle.

There are no records to indicate how long she was incarcerated at Castle Thunder prison in Richmond, or what happened to her after she was released. If the newspapers are correct, Molly Bean was a young woman who enlisted in the 47th North Carolina Infantry some time in the spring of 1863. If the wounds she received were either to the extremities or the head, they would not necessarily have led to her discovery as a woman.

African American Women Soldiers

Before the war, New Bern already had many free blacks who were carpenters, bricklayers, tailors, barbers and sailors, so it is likely that slaves in eastern North Carolina had always seen New Bern as a place of opportunity. During the Civil War, thousands of slaves escaped from their farms and plantations to New Bern which, because it was occupied by the U.S. Army – a free zone, where the Union’s military government protected these contraband refugees from being returned to slavery.

With the military offering jobs, many African American women thrived there. Women who could cook found steady work providing meals for hungry soldiers; housekeepers, laundresses and seamstresses were also welcomed and given employment. One of these workers was Lucy Berington, a 45-year-old African American. The enlistment of women was forbidden therefore her case is something of a mystery.

The U.S. Navy enlisted Lucy as a first-class boy, an entry-level job with a pay scale of seven to nine dollars a month. This would have seemed like a lot of money to Lucy, who was probably a slave before she escaped to New Bern. Her gender was known at the time of her enlistment, and she was assigned as a washerwoman at the U.S. Naval Hospital at New Bern. Lucy is the only known enlisted black female in Civil War-era New Bern, but there may have been others.

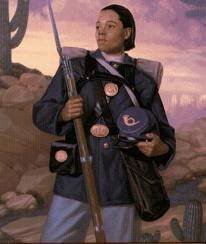

During her adolescence, an African American girl named Cathay Williams worked as a house servant on the Johnson plantation near Jefferson City, Missouri. In 1862, as the Union soldiers moved through Jefferson City, several slaves, including Williams, were confiscated by the 8th Indiana Infantry as contraband. At age seventeen, she was impressed into serving with the 8th Indiana Volunteer Infantry Regiment.

For the next few years, Williams traveled with the 8th Indiana, accompanying the soldiers on their marches through Arkansas, Louisiana and Georgia. She was present at the Battle of Pea Ridge and the Red River Campaign. Later, Williams was transferred to Washington, DC, where she served with General Philip Sheridan‘s command.

After the war was over, Cathay Williams found work as a cook at Jefferson Barracks near St. Louis, but soon decided to join the U.S. Regular Army so that she could be financially independent. On November 15, 1866, she enlisted in the 38th Infantry, a unit of Buffalo Soldiers who served in the American West, protecting settlers as they traveled and set up homesteads. She stood 5 feet 9 inches tall and when asked her name, she replied William Cathay.

She performed regular duties such as working garrison duty or guarding railroads. In an article about her in the St. Louis Times, Williams was described as ‘tall and powerfully built.’ Shortly after her enlistment, Williams contracted smallpox, was hospitalized and rejoined her unit, which by then was posted in New Mexico. In January 1868, her health began to deteriorate again and she was admitted to the hospital at Fort Cummings. She returned to duty after three days but was re-admitted to the hospital in March but returned to duty after three days.

Possibly due to the effects of smallpox, the New Mexico heat or the cumulative effects of years of marching, her body began to show signs of strain and she was frequently hospitalized. The post surgeon finally discovered she was a woman and she was discharged on October 14, 1868. Williams eventually worked her way out to Colorado hoping she would get a land bounty for her military service, but records indicate that her pension claims were denied in 1891.

Women Soldiers and the Women’s Rights Movement

At a time when society viewed female soldiers as either crazed lesbians or overzealous women who wanted to be Joan of Arc, some women were actually passionately patriotic toward their country, not unlike many men who served beside them. Once enlisted, however, women had to keep a low profile in order to keep their true identity hidden.

Women’s rights activists took female soldiers quite seriously. In their six-volume History of Woman Suffrage (1881-1922), Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Matilda Joslyn Gage noted that women were physically capable of performing valiantly in the army; therefore an inability to serve in the military was not grounds to prohibit women’s suffrage:

Though the Mothers of the Rebellion did not ask, and apparently did not think of asking, to share the military duties incident to suffrage, we must discuss it, if we are to consider the subject thoroughly. To be a voting citizen, is to be a possible soldier citizen. There is no way of fulfilling the moral part of the duty, and leaving unfulfilled the physical, and it is cowardly to attempt it. So the question comes, could American women be soldiers? They could, for a few in disguise were in service during the War of Secession…

Historians may differ in their interpretations of the motives or mental state of the women who chose to serve as soldiers in the Civil War, but hundreds of women did fight, and obviously fought well. Most were immediately discharged when their gender was discovered, but I know of none who were drummed out of the army because of cowardice or an inability to perform their soldierly duties.

Therefore, there should be no doubt that many women picked up muskets and fought like men during the Civil War. The service of these brave women supported not only their chosen cause but also the women’s rights movement. Clara Barton stated in 1888:

At the war’s end, woman was at least fifty years in advance of the normal position which continued peace would have assigned her.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Cathay Williams

DeAnne Blanton: Women Soldiers of the Civil War

Women in the Ranks: Concealed Identities in Civil War Era North Carolina