Wife of Union General John Pope

John Pope was a career United States Army officer and Union general in the American Civil War with a reputation for outspokenness and arrogance. He had a brief but successful career in the Western Theater, but he is best known for his defeat at the Second Battle of Bull Run (Second Manassas) in the East. After decades of blaming General Fitz John Porter, an 1879 Board of Inquiry concluded that Pope himself bore most of the responsibility for the loss of that battle.

John Pope was a career United States Army officer and Union general in the American Civil War with a reputation for outspokenness and arrogance. He had a brief but successful career in the Western Theater, but he is best known for his defeat at the Second Battle of Bull Run (Second Manassas) in the East. After decades of blaming General Fitz John Porter, an 1879 Board of Inquiry concluded that Pope himself bore most of the responsibility for the loss of that battle.

Image: Major General John Pope

Born on March 16, 1822, in Louisville, Kentucky, John Pope was raised in Kaskaskia, Illinois, located on the Mississippi River. His father, Nathaniel Pope was the first U.S. District Court judge for Illinois, where Abraham Lincoln practiced law.

John Pope graduated from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in 1842, 17th in a class of 56, a ranking high enough to earn him an assignment to the Army Corps of Engineers. His classmates included the future Confederate General James Longstreet and the Virginia-born, future Union General John Newton. Pope was a stocky, barrel-chested young man of medium height, given to roaring posturing and swaggering.

Pope saw action in the Mexican-American War as a lieutenant of engineers at the Battle of Monterrey on September 21–24, 1846, and on the staff of U.S. General Zachary Taylor at the Battle of Buena Vista on February 22–23, 1847.

On September 15, 1859, Clara Horton married Pope, daughter of Ohio congressman Valentine Baxter Horton. The couple became the parents of four children.

Pope accompanied President-Elect Abraham Lincoln on the inaugural train ride from Springfield, Illinois, to Washington, DC, in February 1861. Pope had met Lincoln a decade earlier. Pope wrote in his memoirs:

I first saw him to know him [Lincoln] personally in Chicago in 1850. Being a citizen of Illinois and having won some small reputation during the Mexican War, but recently ended, Mr. Lincoln, with some of the other lawyers, was good enough to call upon me. The general impression left on my mind was of a tall, gaunt, angular man, very homely and awkward, but with a very intelligent and kindly face.

Pope in the Civil War

At the outbreak of hostilities, John Pope had some eighteen years of service with the United States Army as a civil engineer, but no practical experience commanding troops in battle. Partly because of his political connections, the ambitious and often arrogant Pope secured a commission as brigadier general of volunteers on June 14, 1861. His family’s political power and relationship by marriage to the wife of the president, Mary Todd Lincoln, surely did not hurt his unusually fast rise in rank.

Assigned to the Department of the West, Pope was a competent but fractious commander, who openly schemed against his commanding officer General John C. Fremont, and Pope worked behind the scenes to try to get Fremont removed from command. Fremont was convinced that Pope had treacherous intentions toward him, demonstrated by his lack of cooperation in Fremont’s plans in Missouri.

Lincoln fired Fremont for calling for the emancipation of slaves, and Union troops in the area were reorganized into the Department of the Missouri under Major General Henry Halleck. Because of his reputation as a braggart early in the war Pope was able to generate significant press, which brought him to the attention of General Halleck, who assigned Pope to command the Army of the Mississippi on February 23, 1862.

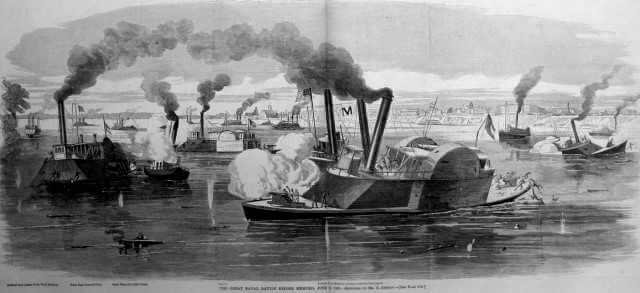

Given 25,000 men, Pope was ordered to clear Confederate obstacles from the Mississippi River. He made a surprise march on New Madrid, Missouri, and captured it on March 14. He then orchestrated a campaign to capture Island Number Ten, a strongly fortified post garrisoned by 12,000 men and 58 guns. His engineers cut a channel that allowed him to bypass the island, then he landed his men on the opposite shore, isolating the defenders. The island garrison surrendered on April 7, 1862, freeing Union navigation of the Mississippi as far south as Memphis.

Pope’s outstanding performance on the Mississippi earned him a promotion to major general. During the Siege of Corinth, Mississippi, he commanded the left wing of Halleck’s army. His aggressiveness won him praise in the army and in the press, but irritated the cautious Halleck.

Pope in the Eastern Theater

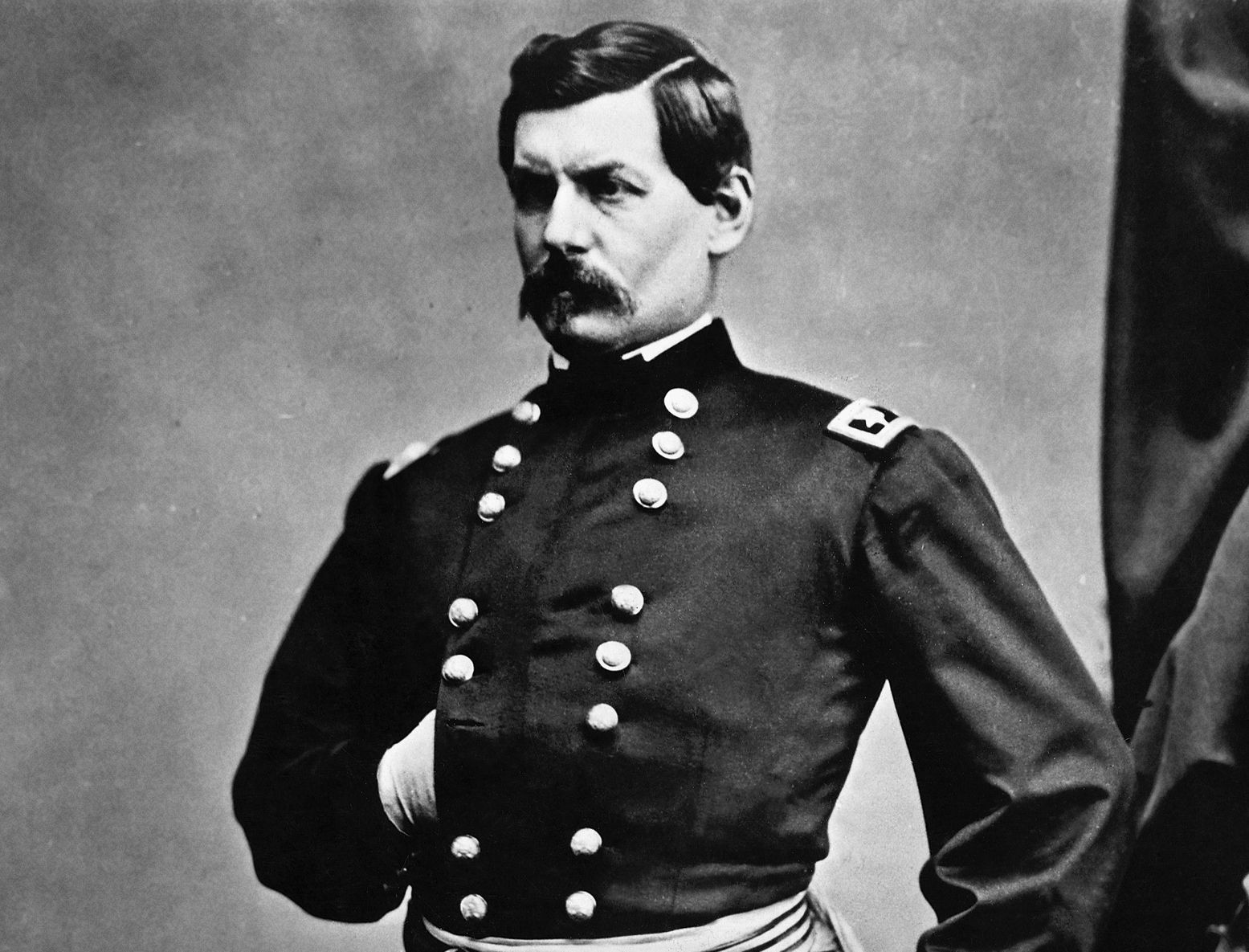

After the failure of the Peninsula Campaign in June 1862, President Lincoln summoned Pope to the Eastern Theater. This promotion infuriated Fremont, who resigned his commission. Pope was not enthusiastic about the transfer either, partly because he was comfortable with his friendly group of subordinates in the West, and partly because he disliked most of the officers in the East, particularly Generals George B. McClellan and Fitz-John Porter.

On June 26, 1862, Union authorities merged the Mountain, Shenandoah and Rappahannock departments into the three-corps Army of Virginia. These units already had performed poorly against CSA General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1862, and it did not bode well that Pope detested corps commanders Franz Sigel and Irvin McDowell, while remaining merely indifferent to the third, Nathaniel P. Banks. Pope’s feelings were largely reciprocated, and he made matters worse after he issued a proclamation that criticized the ability of soldiers in the East, while bragging about his own.

The Lincoln administration counted on Pope to pursue a vigorous campaign designed not simply to defeat Confederates but to punish them. Pope believed the Southern people should pay a price for seceding from the Union and starting a civil war. When his army advanced, he issued orders instructing officers and men to live off the fertile land, taking food and supplies from the civilians.

Pope also implemented stern punishment for guerrillas, and ordered that all male civilians along the route of march be required to swear an oath of allegiance to the Union or be arrested and expelled from the region. If they returned, they would be prosecuted as spies. Finally, he announced that any man or woman who corresponded with anyone in the Confederate Army would be subject to execution. Confederates perceived these to be violations of the tradition of honorable warfare, and in response, General Robert E. Lee labeled Pope a “miscreant,” strong language coming from Lee.

Despite his flaws, Pope was energetic and aggressive, with a zest for fighting – the type of officer Lincoln wanted for the post. His mission was to relieve pressure on McClellan by marching south from Washington, DC, along the Orange & Alexandria Railroad toward Gordonsville, Virginia. If Pope could capture Gordonsville, he could sever the Virginia Central Railroad, which hauled the rich harvest of the Shenandoah Valley to General Robert E. Lee’s army at Richmond.

The first of Pope’s units occupied Culpeper Court House on July 12. During the next two weeks, the remaining commands arrived, and Pope, who came in on the 29th, deployed his troops around the village. Although Pope had opposed the decision, the Union administration retained General Rufus King’s 11,000-man division of McDowell’s corps at Fredericksburg. Pope had roughly 40,000 troops with him at Culpeper.

Despite his bravado, and despite receiving units from McClellan’s Army of the Potomac that swelled the Army of Virginia to 70,000 men, Pope’s aggressiveness exceeded his strategic capabilities. General Lee, sensing that Pope was indecisive, split his 55,000 man army, sending General Stonewall Jackson with 24,000 men as a diversion to Cedar Mountain, eight miles south of Culpeper, where Jackson beat Nathaniel Banks on August 9, 1862.

Second Battle of Bull Run

After sparring with Pope along the Rappahannock River until August 25, 1862, General Lee sent Jackson on a flanking march far into the rear of Pope’s troops. Two days later, Jackson destroyed the Union supply depot at Manassas Junction. This compelled Pope to abandon his defensive line along the Rappahannock and move against Jackson, who had taken a strong defensive position on the site of the First Battle of Bull Run. Pope did not realize that roughly half the Confederate army was between him and Washington, DC.

Headquarters Army of Virginia,

Bristoe Station, August 27, 1862-9 p.m.

Major-General McDowell:

At daylight tomorrow morning, march rapidly on Manassas Junction with your whole force, resting your right on the Manassas Gap Railroad, throwing your left well to the east. Jackson, Ewell, and A.P. Hill are between Gainesville and Manassas Junction. We had a severe fight with them today, driving them back several miles along the railroad.If you will march promptly and rapidly at the earliest dawn of day upon Manassas Junction, we shall bag the whole crowd. I have directed Reno to march from Greenwich at the same hour upon Manassas Junction, and Kearny, who is in his rear, to march on Bristoe at daybreak. Be expeditious, and the day is our own.

John Pope,

Major-General, Commanding.

On August 28, 1862, elements of the Army of Virginia clashed with Jackson at Brawner’s Farm, and the next day, Pope launched several poorly coordinated and unsuccessful assaults against Jackson’s front. That afternoon Pope ordered Fitz John Porter, whose newly arrived corps had come up on his left, to attack Jackson’s right flank. Through no fault of Porter’s, the attack failed to come off, and the fighting ended in a stalemate.

On the morning of August 29, 1862, Pope planned to achieve a great victory over General Jackson’s outnumbered men hunkered down in the bed of an unfinished railroad. Believing that Porter’s 10,000 men would at any moment come sweeping in on the Confederate right with a crushing flank attack, General Pope ordered each valiant but ultimately failed charge. In the railroad cut, General Jackson’s men repulsed seven Union attacks on August 29, 1862.

On the afternoon of August 30, Pope again ordered Porter to attack Jackson, and again the attack failed to happen. Unbeknownst to Pope, CSA General James Longstreet had reached the battlefield the night before, and had deployed 18 cannon on a ridge between the two wings of the Confederate army. The gunners had “a beautiful position in easy range” of the Federals, and their fire wrecked the oncoming Union lines.

Then, at 4:30 pm, Longstreet unleashed his infantry, which rolled forward like an avalanche. When Pope saw the attacking Rebels, he gaped in surprise. According to one of his staff officers, for the first time in the campaign the general “showed strong excitement.” All that stood in the immediate path of Longstreet was the 1100-man brigade of Colonel Gouverneur Warren and a six-gun battery.

Longstreet’s soldiers crushed Warren’s brave command and overran the battery. Driving across Young’s Branch, the Confederates met stiff Federal resistance along Chinn Ridge. Five Union infantry brigades, supported by artillery, fought stubbornly, inflicting heavy casualties on Longstreet’s units. The Federals held the position for the better part of an hour, buying time for their comrades to retire toward Centreville.

Image: The Stone House

Image: The Stone House

This was a common landmark during both the Battles of First and Second Manassas. Used as a hospital for wounded soldiers, this home still stands at the intersection of the Manassas/Sudley Road and the Warrenton Turnpike. This intersection controlled the battlefield allowing those who possessed it to move about with relative ease.

Jackson advanced at 6 o’clock, pushing the Federals before him. Another valiant defense by Union units on Henry House Hill ended the action. The defeated Northerners retired in order from Second Manassas; it was not a rout like First Manassas. The rain began falling about 8 o’clock. Pope’s Army of Virginia had suffered a decisive and humiliating defeat.

After holding on to the Henry House Hill and the vital intersection it commanded, Pope ordered the retreat. The Army of Virginia had lost almost 14,000 men at Second Bull Run; Pope was blamed for the defeat. A staff officer later recalled that “Pope was entirely deceived and outgeneralled. His own conceit and pride of opinion led him into these mistakes.”

John Hay, Lincoln’s secretary, recorded in his diary on September 1, 1862:

Every thing seemed to be going well and hilarious on Saturday, and we went to bed expecting glad tidings at sunrise. But about Eight oclock, the President came to my room as I was dressing and, calling me out, said, “Well, John, we are whipped again, I am afraid. The enemy reinforced on Pope and drove back his left wing, and he has retired to Centreville where he says he will be able to hold his men. I don’t like that expression. I don’t like to hear him admit that his men need holding.”

After a while, however, things began to look better and people’s spirits rose as the heavens cleared. The President was in a singularly defiant tone of mind. He often repeated, “We must hurt this enemy before it gets away.” And this morning, Monday, he said to me when I made a remark in regard to the bad look of things, “No, Mr. Hay, we must whip these people now. Pope must fight them. If they are too strong for him, he can gradually retire to these fortifications. If this be not so, if we are really whipped and to be whipped, we may as well stop fighting.”

After the Second Battle of Bull Run, Pope went to the White House to read a report complaining about fellow generals. The Cabinet refused to allow publication of his criticisms. Pope compounded his unpopularity by blaming his defeat at Second Bull Run on General Fitz John Porter’s failure to attack the first day. Pope saw to it that Porter was court-martialed and dismissed from the army.

Pope in the West

On September 6, 1862, President Lincoln relieved Pope of command, and his army was merged into the Army of the Potomac ten days later. Pope was assigned to duty as commander of the Department of the Northwest, with headquarters at St. Paul, Minnesota. During 1863 and 1864, General Pope directed operations against the Sioux, and by 1865, was the US Army’s foremost expert on Indian affairs.

Pope continued to be abusive toward the President, writing a friend that Mr. Lincoln was “feeble, cowardly and shameful.” Pope adopted a scorched earth policy against the Sioux uprising there and arrested Indians for rape and murder. Lincoln commuted the death sentences of many convicted of those crimes.

In February 1865, Union General-in-Chief Ulysses S. Grant reassigned Pope to command the Military Division of the Missouri, the second-largest geographical command in the United States. He held until he was relieved by General William Tecumseh Sherman on August 11, 1866. Pope was brevetted to major general on March 13, 1865, for his role in the capture of Island Number Ten, Mississippi.

After the Civil War, Pope was mustered out of the volunteer army but remained in the army as a brigadier general.

In April 1867, he was appointed governor of the Reconstruction Third Military District – Georgia, Florida, and Alabama – with his headquarters in Atlanta, banning city advertising in newspapers that did not favor Reconstruction, issuing orders that allowed African Americans to serve on juries, and vigorously defending the voting rights of African Americans.

President Andrew Johnson removed Pope from command December 28, 1867, replacing him with General George Meade. After a brief stint as commander of the Department of the Lakes in Detroit, Michigan, Pope returned to the Plains and commanded the Department of the Missouri from 1869 until 1883. He was an architect of the Red River War (1874–1875), which subdued the Southern Plains tribes.

Blaming white encroachment for Indian troubles, Pope engendered controversy by calling for better and more humane treatment of Native Americans. He made political enemies in Washington by recommending that the reservation system would be better administered by the military than the corrupt Indian Bureau.

Pope’s Final Years

John Pope’s reputation suffered a serious blow in 1879 when a Board of Inquiry led by General John Schofield concluded that Fitz John Porter had been unfairly convicted, and that it was Pope himself who bore most of the responsibility for the loss at the Second Battle of Bull Run. The report characterized Pope as reckless and dangerously uninformed about the events on the battle, and credited Porter’s perceived disobedience with saving the army from complete ruin.

Pope was promoted to major general on October 26, 1882, on the basis of his seniority. After forty-four years of service, Pope retired from the army on March 16, 1886.

Clara Pope died in 1888.

Pope wrote his memoirs for the National Tribune, which serialized the book between February 1887 and March 1891. He wrote that President Lincoln “was no more a saint than Washington and I presume no more of a sinner, but, like General Washington, he had weaknesses and peculiarities of his own, which need to be much more fully set forth before we can know him as he was and as I have doubt he would prefer that his memory should be transmitted to his posterity.”

General John Pope died in his sleep on September 23, 1892, at the Ohio Soldiers’ Home near Sandusky, Ohio, at the age of 70. His brother-in-law, General Manning F. Force, was with him when he died. He was buried beside his wife in Bellefontaine Cemetery in St. Louis, Missouri.

SOURCES

Encyclopedia Virginia

Wikipedia: John Pope

The Handbook of Texas Online

Cincinnati Civil War Roundtable

Mr. Lincoln’s White House: John Pope

The American Civil War: Battle of 2nd Manassas / Bull Run

Historynet.com: General Pope Was No Match for Robert E. Lee