Freed Slaves Betrayed by the Union Army

On December 9, 1864, USA General Jefferson C. Davis (not to be confused with Confederate President Jefferson Davis) and his men reached Ebenezer Creek some twenty miles north of the city of Savannah, Georgia. Davis was leading his XIV Army Corps toward that city during General William Tecumseh Sherman‘s March to the Sea during the autumn of 1864.

Near Savannah, Georgia

Backstory

Excerpts from Historynet’s article: Betrayal at Ebenezer Creek:

Brigadier General Jefferson C. Davis had few complaints about the able-bodied black men who were supplying the muscle and sweat to keep his Union XIV Corps on the move with Major General William T. Sherman’s 62,000-man army. The black ‘pioneers’ were making the sandy roads passable for heavy wagons and removing obstacles that Rebel troops had placed in his path. Davis was irritated by the few thousand other black refugees following his troops. He had been unable to shake them since the Union army stormed through Atlanta and other places in Georgia in late 1864, liberating the slaves from their owners.

The Union Army fed and cared for the male African Americans who were clearing a path for them to follow, as well as the refugees who worked as teamsters, cooks, and servants. Army officials did not assume responsibility for the hundreds of hangers-on – hundreds of black women, children, and older men – who came into camp every day begging for food. Captain Charles Hopkins of the 13th New Jersey Infantry later recalled:

The rich, rolling uplands of the interior were left behind, and we descended into the low, flat sandy country that borders for perhaps a hundred miles upon the sea. … The country is largely filled with a magnificent growth of stately pines, their trunks free – for sixty or seventy feet – from all branches. … These pine woods, though beautiful, were not fertile and rations – particularly of breadstuffs – began to fail and had to be eked out [supplemented] by rice, of which we found large quantities; but also found it, with our lack of appliances, very difficult to hull.

In addition to causing a severe shortage of food and other items, the refugees who followed Davis and his XIV Corps also slowed down his march, testing his volatile temper. Davis was anxious to lead his force to Savannah and be done with General Sherman’s March to the Sea, a slow meandering campaign across the state of Georgia. Then a new aggravation presented itself in the form of General Joseph Wheeler and his Confederate cavalry corps, who were a constant hindrance and annoyance in their rear. Quicker movement would make it easier to evade the Rebel horsemen as well as to defend against them.

Ebenezer Creek

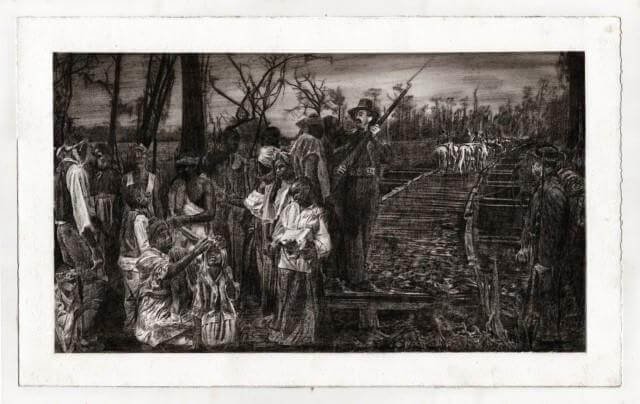

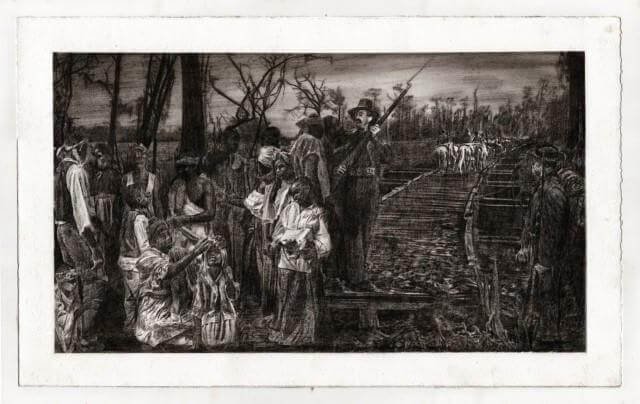

On December 8, 1864, the Union XIV Corps under Brigadier General Jefferson C. Davis reached the western bank of the 165-feet-wide and 10-feet-deep swollen and icy Ebenezer Creek. While the corps engineers began assembling a pontoon bridge for the crossing, Wheeler’s Southern cavalry approached close enough to sporadically shell the Union lines.

Charcoal on paper by Isaac McCaslin

By midnight the pontoon bridge was ready, and Davis’ 14,000 men, horses and wagons began their crossing. Hundreds of freed slaves were anxious to go with them, but Davis ordered his provost marshal to prevent them from crossing. Colonel Charles Kerr of the 126th Illinois Cavalry, which was at the rear of the XIV Corps, recalled:

On the pretense that there was likely to be fighting in front, the Negroes were told not to go upon the pontoon bridge until all the troops and wagons were over. … A guard was detailed to enforce the order. But, patient and docile as the Negroes always were, the guard was really unnecessary. …

Betrayal of Trust

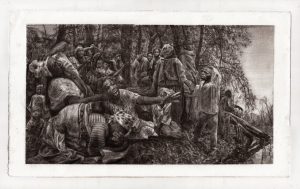

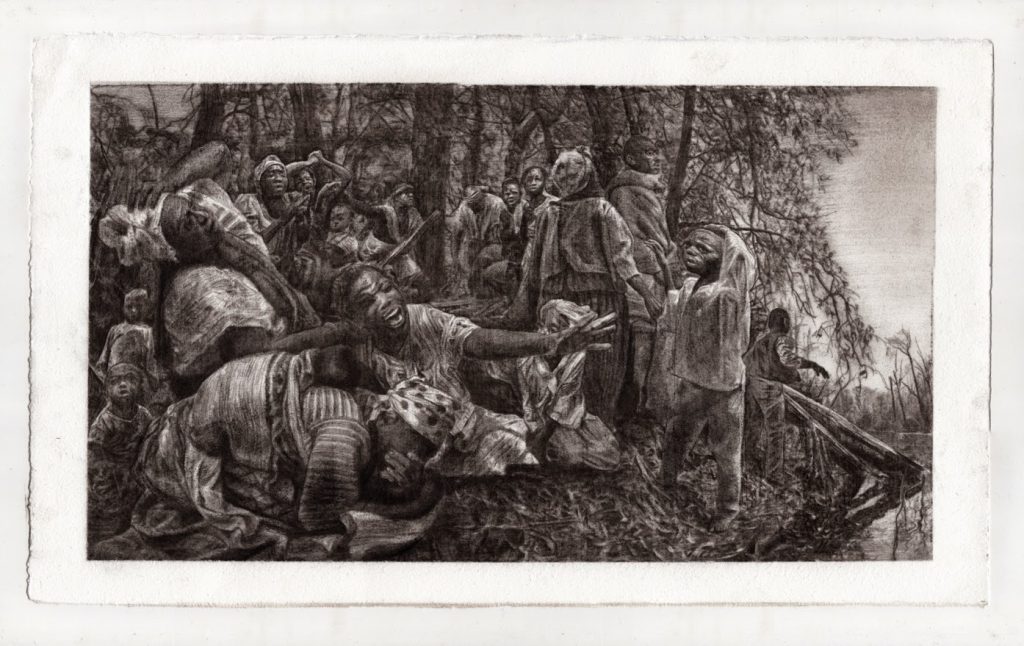

Maybe the newly-freed slaves should have sensed they were in danger, but in their trusting minds the soldiers of the Union Army were their saviors and would do them no harm. As the last Union soldiers reached the eastern bank on the morning of December 9, the engineers abruptly disassembled the bridge. Colonel Charles Kerr of the 126th Illinois Cavalry continues:

Orders were given to the engineers to take up the pontoons and not let a Negro cross. The order was obeyed to the letter. I sat upon my horse then and witnessed a scene the like of which I pray my eyes may never see again. … [Amid] cries of anguish and despair, men, women, and children rushed by the hundreds into the turbid stream, and many were drowned before our eyes. From what we learned afterwards of those who remained on land, their fate at the hands of Wheeler’s troops was scarcely to be preferred.

On realizing their plight, a panic set in amongst the freedmen, who knew that Confederate cavalry were nearby. Whole families rushed into the icy, swollen Ebenezer Creek – old and young alike, men and women and children, swimmers and non-swimmers, determined not to be left behind. Hundreds of freed slaves drowned trying to swim the chilling waters to escape the pursuing Confederates. In the uncontrolled, terrified rush of humanity, many were swept under the surface.

On the eastern bank, some of Davis’ soldiers helped those they could safely reach. Others felled trees into the water. Several of the freedmen lashed some logs together into a crude raft, which they used to rescue those they could and then to ferry others across the stream, but it was a slow process.

While this was going on, scouts from General Wheeler’s Confederate cavalry arrived, fired briefly at the soldiers on the far bank, and left to summon the rest of Wheeler’s force. Officers from the XIV Corps ordered their men to leave the scene, and they resumed their march. The freedmen continued to ferry as many as possible across the stream on the makeshift raft.

Major General Oliver O. Howard, commander of the right wing of Sherman’s army (which included Davis’ corps), recalled seeing:

… throngs of escaping slaves … from the baby in arms to the old Negro hobbling painfully along the line of march; Negroes of all sizes, in all sorts of patched costumes, with carts and broken-down horses and mules to match.

Because the able-bodied men were up front clearing a path for Davis and his army, most of those left stranded were women, children, and old men. When Wheeler’s cavalry arrived in force, those refugees who had not made it to the eastern bank, or drowned in the attempt, were enslaved once more.

Davis’ orders infuriated several of the Union men who witnessed the ensuing calamity, including Major James A. Connolly who described the events in a letter to the Senate Military Commission, which found its way into the press. Radical Republicans in the U.S. Congress, like Charles Sumner and Thaddeus Stevens, for some time had pushed for land redistribution in order to break the back of Southern slaveholders’ power.

Feeling pressure from within his own party, in January 1865 President Abraham Lincoln sent Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton to Savannah to discuss the incident with Davis and Sherman. Davis defended his actions as a matter of military necessity, with Sherman’s full support.

Sherman’s Special Field Order No. 15

On January 16, 1865, Union General William Tecumseh Sherman issued Special Field Order No. 15, which confiscated as Union property roughly 400,000 acres of land. Included in this property were a strip of coastline stretching from Charleston, South Carolina to the St. John’s River in Florida, Georgia’s Sea Islands, and the mainland thirty miles in from the coast. Under Special Field Order No. 15 those lands were redistributed to newly freed black families in forty-acre segments, which provided for the settlement of roughly 40,000 blacks.

Thereby, Sherman’s army was relieved of the burden of supporting the freedpeople as it turned north into South Carolina. But Order No. 15 was a short-lived gift for those black families. After the Lincoln assassination, President Andrew Johnson ignored Sherman’s Order No. 15 and the the objections of General Oliver O. Howard, who had been appointed the head of the Freedmen’s Bureau. In the fall of 1865, Johnson returned most of the land along the South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida coasts to the planters who had originally owned it.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Ebenezer Creek

Historynet: Betrayal at Ebenezer Creek

The Civil War Picket: Betrayal at Ebenezer Creek

New Georgia Encyclopedia: Sherman’s Special Field Order No. 15