Daughter of Confederate General Robert E. Lee

The Lee daughters had impressive pedigrees. They were direct descendants of the aristocratic Lees of Virginia and England, as well as George and Martha Washington. Mrs. Robert E. Lee’s father, George Washington Parke Custis, was the first president’s adopted son and the man who established the 1,100-acre plantation called Arlington. Several years later, Custis built Arlington House (1817), the ancestral home of the Custises and Lees on the Potomac River overlooking Washington DC.

Agnes Lee

Eleanor Agnes Lee, born February 27, 1841, was called Agnes. She was the third of four daughters and the fifth of seven children of Mary Anna Custis and Robert E. Lee, born at the family’s Virginia estate, Arlington. As a child, Agnes spent much of her time reading, studying, playing piano and working in her garden. There was also a steady flow of visitors and playmates, cousins from their large extended family, and a host of friends.

Agnes loved Arlington dearly and took great interest in the changes made in the house, especially when the Lees refurnished the large hall in 1855. She also helped teach the slaves at Arlington, a practice her mother had begun years earlier, knowing that educating slaves in Virginia was punishable by law. Agnes held a Sunday evening school for the slaves and taught individual children before and after breakfast.

Agnes received an excellent education for a woman of her era. She and her sister Annie were taught at home by a tutor, Miss Sue Poor, from whom they learned music, English composition, French, and arithmetic. During her childhood years, Agnes kept a journal of her life at Arlington that was published as Growing Up in the 1850s (1984). In 1855 Agnes began attending boarding school at the Virginia Female Institute in Staunton.

Anne Carter Lee

Anne Carter Lee, the second daughter of Robert E. Lee and Mary Randolph Custis Lee, was born June 18, 1839 at Arlington House. Called Annie by friends and family, her rich black hair was much like her father’s when he was young. As a child, Annie lost her sight in one eye after a childhood accident with a pair of scissors and suffered from a disfigured eye. She loved her family, but she was close to only Agnes and her father.

Image: Anne Hill Carter Lee

Image: Anne Hill Carter Lee

Robert E. Lee’s mother, Annie’s grandmother.

No authenticated image of Annie Lee is known to exist, but descriptions of her indicate that she might have looked like his mother, for whom she was named. A post about Anne Hill Carter Lee is available at my History of American Women blog.

Robert E. Lee had a special bond with Annie, whom he nicknamed Little Raspberry because she had a reddish birthmark on her face as an infant. She was a gifted young woman but very shy because of her disfigured eye. Annie and Agnes were known as The Girls by the family; they were so close they were often thought of as twins.

Annie had recently taken over some household duties because her mother was suffering terribly with rheumatoid arthritis. General Lee had worried that the job would be too physically demanding for Annie. She was never physically strong, and he constantly worried about her health.

Civil War

Agnes Lee was twenty years old at the start of the war that left her family homeless and her father a hero; Annie was twenty-one. Arlington House had been home to the Lees two months shy of 30 years when Robert E. Lee declined the command of Federal troops offered by President Abraham Lincoln. He left Arlington on April 20, 1861 to join the Confederate Army, never to return. The three Lee sons volunteered their services to the Confederacy as well.

Although her husband kept urging her to leave, Mary Randolph Custis Lee delayed evacuating Arlington House until May 15, 1861, possibly because travel was difficult for her. After the birth of her second child, Mary Custis Lee, Mrs. Lee had sustained a pelvic infection that soon after developed into rheumatoid arthritis. Her condition worsened as she grew older. By 1861, she was using a wheelchair.

Mrs. Lee looked longingly at her beloved home as they pulled away, hoping she would soon be able to come back. However, as time passed, it became abundantly clear that she would not be able to return anytime soon, if ever. Agnes, Mrs. Lee and the other Lee daughters were vagabonds during the first year of the war, moving from one family plantation to another. They eventually settled at a rented townhouse in Richmond.

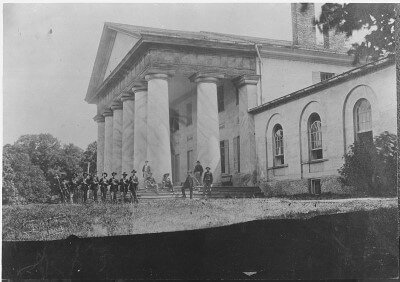

Image: East Front of Arlington

Image: East Front of Arlington

With Union soldiers on the lawn

When Union troops occupied Arlington in June 1862, Mrs. Lee and the general decided to remove Annie and Agnes from war-torn Virginia and send them to White Sulphur Springs. This was a popular resort owned by friends outside of Warrenton, North Carolina, far away from the theater of war.

Several months after Agnes and Annie arrived at White Sulphur Springs, Annie contracted typhoid fever. Agnes never left her side, not even when others warned that she could become ill with the disease as well. Agnes risked her life to be by Annie’s side, providing whatever care and comfort she could.

Annie Lee died of typhoid fever October 20, 1862, at the age of 23, while Agnes held her. A young relative said that Annie’s death “was a shock to Agnes from which she never recovered.”

When Annie died, it was not possible to take her body back to Virginia for burial without crossing enemy lines. The owner of White Sulphur Springs generously offered to have her Annie buried in his family cemetery and the Lees gratefully accepted. A disabled Confederate veteran sculpted an obelisk for her grave.

Robert E. Lee was in the field in Virginia recovering from the Battle of Antietam when he received a letter notifying him of Annie’s death. The unexpected news left him devastated.

Orton Williams

Martha Custis Markie Williams was a first cousin once removed of Mrs. Robert E. Lee and a direct descendant of Martha Washington. Markie and her siblings grew up at Tudor Place in Georgetown Heights, across the Potomac River from Arlington House. They were orphaned in September 1846 when their father gave his life at the Battle of Monterrey during the Mexican-American War. Markie’s youngest brother, William Orton Williams, called Orton, was only seven years old. By previous arrangement George Washington Parke Custis, Mrs. Lee’s father, became Orton’s guardian, and he grew up at Tudor Place and Arlington.

There is evidence that a romantic attachment developed between Agnes Lee and Orton Williams in the months before the Civil War. Agnes would have been about 20 at the time. Her father disapproved of the romance, and he ample reason. Robert E. Lee had helped Orton get a position as 2nd lieutenant in the Second Cavalry of the United States Army. Orton was assigned to Commander-in-Chief General Winfield Scott’s staff, and he soon became Scott’s private secretary.

Fearing that he might have learned something while working for Scott that could benefit the Confederate army, Williams was imprisoned for several weeks. After he was released, he served on Lee’s staff until rumors began to circulate that he had been spying for Lee at General Scott’s headquarters, and gathering information for Lee. Orton then transferred to the staff of General Leonidas Polk at Columbus, Kentucky. Shortly after he arrived, he wrote to his cousin Walter Gip Peter to come west and serve with him.

In April 1862, Orton received high praise from his superior officers, Generals Braxton Bragg and P.G.T. Beauregard, for his performance at the Battle of Shiloh, a major battle in the Western Theater of the Civil War.

Agnes and Orton

On furlough at Christmastime in 1862, Orton Williams visited the Lee family at Hickory Hill, home of Ann Butler Carter Wickham, sister of Robert E. Lee’s mother. Orton and Agnes had ridden together and seemed to enjoy each other’s company. His Christmas presents to her, a riding whip and a pair of gauntlets, were among her most treasured gifts.

On Christmas Day, Orton asked to speak to Agnes alone in the parlor. No one knows what happened between Agnes and Orton in the parlor, and from then on Agnes refused to talk about it. A family member who was at Hickory Hill as a child later wrote:

We could not understand it. After a long session in the parlor from which we children had been warned to stay away, he came out, bade the family good-bye and rode away alone.

By all accounts she still loved him deeply, but for reasons never made known, Agnes must have rejected the young man’s proposal. Perhaps two years of war had changed young Orton Williams. He had a reputation in the army for being brave yet reckless, even unpredictably violent, and it was rumored he had become much too fond of drink. Miss Agnes Lee would not have approved of any of those traits.

The following spring, Colonel Orton Williams received two letters, one written by Robert E. Lee on April 7, 1863 and the other from cavalry General J.E.B. Stuart. Those letters seem to verify that Williams was soon to be promoted to brigadier general and that he was coming back to Virginia to serve under Stuart. This news should have been a dream come true for Orton – which makes his subsequent actions even more difficult to understand. Perhaps his failure to win Agnes’ hand had made him even more reckless.

In any case, on June 8, 1863, officials captured Orton Williams and his cousin Gip, dressed as Union officers, behind Union lines near Franklin, Tennessee. With forged papers, Orton introduced himself as Colonel Lawrence W. Auton and his companion (Gip) as Major Dunlap. Their assignment, he said, was to examine all posts. Although they did not behave like spies, nor did they seem interested in information spies would want to know, their actions aroused suspicion.

Image: Colonel William Orton Williams

Image: Colonel William Orton Williams

Orton and Gip were detained for verification of their passes, and when these were declared false, they were arrested. Under intense questioning, they admitted they were Confederate officers but denied that they were spies. Tried by drumhead court-martial (held in the field to hear urgent charges) that very night – June 8 – Orton and Gip were found guilty of spying. They eventually confessed their identity but maintained they were not spies. They were hanged early on the morning of June 9, 1863.

In the few hours allowed him before his execution, Williams wrote a brief note to his sister Markie, who sent a copy to Agnes:

Do not believe that I am a spy. With my dying breath I deny the charge. Do not grieve too much for me. … Altho I die a horrid death I will meet my death with the fortitude becoming the son of a man whose last words to his children were, “Tell them I died at the head of my column.”

Orton Williams carried with him to his death a picture of Agnes, the novel Paradise Lost. His final letter to Agnes stating that if his mission had been successful they would have been married in Europe in July.

Though they suffered in silence, the Lees were devastated by the death of this young man. General Lee was outraged over his execution, and later said, “… my blood boils at the thought of the atrocious outrage, against every manly and Christian sentiment which the Great God alone is able to forgive.” After the bodies of these young men were reburied in Oak Hill Cemetery in Georgetown, the families finally began to heal.

The deaths of Annie Lee and Orton Williams greatly affected Agnes Lee’s health. General Lee’s light-hearted daughter became a distant figure, damaged and care-worn beyond her years. Thereafter she was perceived as rather reserved and aloof. One of the Lee family biographers observed: “They were seeing not pride, but a mask for sorrow.”

The execution of Orton Williams by the Union Army for spying has since been one of the most tragic incidents of the War Between the States. It has been suggested that they were acting on a bet made with fellow Confederate officers. If there was a purpose to the mission of these two young men, it has never been revealed.

To Lexington

After the surrender of his army at Appomattox in April 1865, Robert E. Lee was still “a civilian with means of livelihood.” After refusing several other offers, he accepted the presidency of Washington College, now Washington and Lee University. At the age of 24, in October 1865, Agnes moved with her family to Lexington, Virginia. The Lees first settled into the President’s House at the college, then later into a new home the General had built with all the modern conveniences of the day.

After several years of nothing but turmoil, the Lees began a more peaceful time in their lives. Lee’s daughters were only responsible for supporting the new president socially and helping to care for their invalid mother. But during the first year at Lexington, Agnes’ already fragile health took another blow. According to her father, left her steady and regular but without velocity. In a letter to his son, Rooney, General Lee wrote:

On my return I found Agnes quite sick, she having been taken with fever the day I left. She is better I hope, poor child, but terribly reduced and prostrated, nor is she yet relieved of her disease.

In his role as president of Washington College, Robert E. Lee proved his worth, revitalizing one of Virginia’s most respected institutions. He created new academic programs, including the establishment of the first School of Journalism in the United States.

Their Last Hurrah

However, by 1870, Lee was tired and his poor body was older than his 63 years. In March 1870 his doctors urged him to embark upon a journey to restore his health. In March 1870 Robert E. Lee began a two-month journey to visit the graves of his daughter Annie and his father, Henry Light Horse Harry Lee of Revolutionary War fame. Agnes accompanied him and served as her father’s companion and nurse.

On March 28, 1870, the General and Agnes left on a train for Warrenton, in northeastern North Carolina. They arrived at 10 o’clock that night and received a warm welcome at Ingleside, the home of Mr. and Mrs. John White. The next morning, their hosts provided them with many bouquets of white hyacinths and gave Lee and Agnes a horse and carriage so they could visit the cemetery alone. There, Agnes covered Annie’s grave with flowers.

Many people called to see the General that evening; he wrote to his wife: “I was glad to have the opportunity of thanking the kind friends for their care of [Annie] while living and their attention to her since her death. I saw most of the ladies of the committee who undertook the preparation of the monument and the enclosure of the cemetery. …”

They later took a steamer from Jacksonville, Florida to Cumberland Island off the coast of lower Georgia. Lee’s father, Revolutionary War hero Henry Light Horse Harry Lee, had died there in 1818 while visiting his friend, General Nathanael Greene. When the boat tied up at Cumberland Island, Lee and Agnes went ashore to the burial ground. Lee later wrote: “… Agnes decorated my father’s grave with beautiful fresh flowers. … I presume it is the last time I shall be able to pay to it my tribute of respect. The cemetery is unharmed and the grave is in good order, though the house of Dungeness has been burned and the island devastated.”

The body of Lee’s father, Revolutionary War General Henry Light Horse Harry Lee, was later disinterred at Cumberland Island and moved to the family crypt at Washington and Lee University.

Unfortunately, rather than improving their health, the six-week journey had exhausted both Agnes and her father. The South’s greatest hero was celebrated at every stop along their way, but at some places, General Lee was simply too weak to leave the train. They returned to Lexington in early May, with another summer of work and college society following. Agnes remained fragile, and the General had noticeably weakened.

In late September the General suffered a stroke from which he never recovered. He died in his home on October 12, 1870, surrounded by his beloved family.

If Agnes had any joy in her life after her father’s death, it was not evident. In a letter to a friend who had moved to Havana, she wrote: “How this warm island you were on when you wrote contrasts with the snow here that has lain on the ground a month, and the canal which is one great source of supply to this place has been frozen for that length of time. … I should like to spend a winter with you where there is no winter. … We are in a land of strangers to you. Good – very Presbyterian, kind, but not so winning in their manners as those we have been accustomed to. … I am housekeeper and find it quite a change with an ignorant girl for cook, and the mistress no wiser!”

Considered her mother’s favorite daughter, like the other Lee girls, Agnes had never married. Eleanor Agnes Lee contracted typhoid fever and passed away in Lexington October 15, 1873 – three years and three days after her beloved father. She was only 32 years old. Her last wish was to be buried in the dress she wore on Christmas Day 1862, the day she refused Orton’s proposal of marriage.

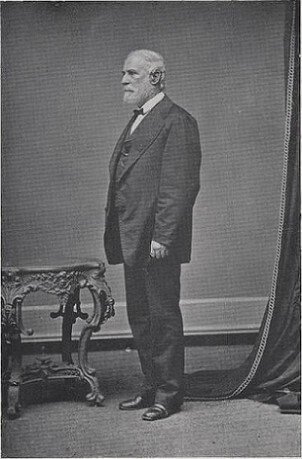

Image: Robert E. Lee

Shortly before his death in 1870

Mary Randolph Custis Lee passed away on November 5, 1873, three weeks after Agnes. The remaining members of the Lee family – including surviving daughters Mary Custis and Milly – must have been stunned by so much death in such a short time.

In 1994, Annie Lee’s remains were moved to the Lee crypt in Lexington.

SOURCES

Arlington House: Anne Carter Lee

Arlington House: Eleanor Agnes Lee

R.E. Lee: a Biography, Volume 3, Chapter XII

R.E. Lee: A Biography, Volume 4, Chapter XXV

High Bridge Publications: Eleanor Agnes Lee: A Sweet Quiet Sadness