Wife of Lt. Colonel Walter Herron Taylor: Aide to General Robert E. Lee

Elizabeth Selden Saunders was the daughter of United States Navy Captain John L. Saunders and Martha Bland Selden Saunders During the Civil War, she lived during the war with the family of Lewis Crenshaw in Richmond, Virginia, where she worked at the Confederate Mint and the Confederate Medical Department.

Elizabeth Selden Saunders was the daughter of United States Navy Captain John L. Saunders and Martha Bland Selden Saunders During the Civil War, she lived during the war with the family of Lewis Crenshaw in Richmond, Virginia, where she worked at the Confederate Mint and the Confederate Medical Department.

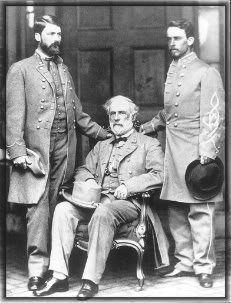

Image: A week after Appomattox, a series of photographs were taken on the back porch at General Robert E. Lee’s home in Richmond by Mathew Brady’s firm. As General Lee wore his uniform for the last time, he posed with his oldest son Major General George Washington Custis Lee and Colonel Walter Taylor (right), husband of Elizabeth Saunders Taylor.

Walter Herron Taylor was born on June 13, 1838, in Norfolk, Virginia. He was the son of Richard and Elizabeth Calvert Taylor, and a descendent of Adam Thoroughgood (1604–1640), an early leader who is widely credited for the naming of Norfolk County and the Lynnhaven River in the earliest days of the 17th century.

Taylor attended Norfolk Academy before enrolling in the Virginia Military Institute in Lexington, Virginia, in 1853. In 1857, Taylor returned to Norfolk after his father died during a yellow fever epidemic, and took over his father’s business. Like many other young Virginians, Taylor joined a volunteer militia company in Norfolk following John Brown’s failed raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in 1859.

Taylor in the Civil War

When Virginia seceded in May 1861, Taylor entered the Confederate Army with his company. On May 2, 1861, he was promoted from his infantry company to the headquarters of the Army of Virginia. At the age of 23, he was assigned as adjutant to General Robert E. Lee after Lee was appointed commander of Virginia’s military forces.

Taylor dealt with Lee on a daily basis, interacting with him on a personal as well as a professional level. He frequently complained that Lee put too much work on him, but Taylor was also devoted to the man whom he affectionately called The Great Tycoon.

Taylor would remain with Lee for the rest of the war, rising from a rank of captain to lieutenant colonel on December 12, 1863. Taylor wrote, “it was my peculiar privilege to occupy the position of a confidential staff-officer with General Lee during the entire period of the War for Southern Independence.”

When General Lee assumed command of the Army of Northern Virginia in June 1862, during the Peninsula Campaign, Taylor became assistant adjutant general of that army. He was an exceedingly capable and tireless worker with many responsibilities. And since Lee was noted for his small, over-worked staff, Taylor carried an enormous burden on his young shoulders.

He was effectively the Chief Aide-de-Camp to General Lee throughout the war. He wrote dispatches and orders for Lee, performed personal reconnaissance, and often carried messages in person to corps and division commanders. He greeted all persons who came to see Lee, and usually decided whether they would be announced to the General.

During the war, Taylor’s fiancee, Elizabeth Saunders, lived at the boardinghouse of the Lewis Crenshaw family in Richmond, Virginia, where she worked at the Confederate Mint and for the Surgeon General in the Confederate Medical Department.

In the last few days of the Siege of Petersburg, as it became clear to Lee and his staff that Petersburg was lost and Richmond should be evacuated, 26-year-old Walter Taylor received special permission from General Lee to go to Richmond to give Miss Saunders “the protection of his name.”

Taylor sent a messenger ahead to Richmond to advise his bride-to-be to make arrangements with Reverend Dr. Charles Minnigerode, the rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church. On the night of April 2, 1865, after the evacuation plans for Petersburg had been laid, Taylor caught the last train to the Confederate capital.

During the early hours of April 3, 1865, while the evacuating Confederates fired the city and looters ran wild in its streets, Taylor and Miss Saunders were married in the parlor of the Crenshaw house.

Taylor then returned to the Army of Northern Virginia, remaining with the army until the surrender at Appomattox Court House on April 9. One week later, Taylor was the only staff officer to accompany General Lee back to Richmond. There, he posed on the back porch of a home on Franklin Street for the famous Brady photograph with Lee and his son Custis.

After the War

After leaving General Lee, Taylor picked up his bride in Richmond and drove her to Norfolk in a buggy. Taylor resumed the banking business in Norfolk and also worked as an attorney.

During the years following the Civil War, Walter and Elizabeth Taylor had four sons and four daughters, and his family came first in every aspect of his life. Their sons were Walter Taylor III, Richard C. Taylor, J. Saunders Taylor and Robert E. Lee Taylor; their daughters were Bland, Thomlin, Steele, and Elizabeth Taylor.

He lived the life of a Virginia gentleman and businessman, serving as Senator in the Virginia General Assembly, and attorney for the Norfolk and Western Railway. He engaged in the hardware business for a few years with his partner Andrew S. Martin and the business eventually operated as the W.H. Taylor and Company.

On April 30, 1870, General Lee paid his last visit to Norfolk, accompanied by his daughter, Agnes Lee. He arrived in Portsmouth via railroad from North Carolina, and was met by Colonel Taylor. His former aide escorted him through the waiting crowds to ride to Norfolk on the Elizabeth River ferry. He died less than five months later.

When General Lee passed away on October 12, 1870, among those who attended his funeral was Colonel Walter Taylor, who said his last goodbye to the man he had come to love and respect.

Taylor held municipal offices and was elected to the Virginia General Assembly, where he served as a Senator representing Norfolk from 1869 until 1873. In 1870, he was named an honorary graduate of his class at the Virginia Military Institute, and served his first stint on the Virginia Military Institute Board of Visitors 1870-1873, and again 1914-1916.

In 1877, Taylor became president of the Marine Bank of Norfolk, in which capacity he served for thirty-nine years. He also served on the Board of Directors of the Norfolk and Western Railroad.

Taylor devoted a considerable portion of his postwar years to settling controversies related to the Army of Northern Virginia and in defense of General Lee. Taylor was recognized by former generals from both sides of the war as an unofficial court of last resort in settling disputes about the war.

In general, the Lost Cause view of the war stressed that the Civil War had not been about slavery, that Northern numbers and industrial might made the South’s defeat inevitable, and that Lee had been a nearly infallible general, whose defeats (most notably at Gettysburg in 1863) came because of malingering subordinates, particularly General James Longstreet.

Taylor was petitioned by so many generals for so much information, he decided to write a book to set the record straight. He asked for permission from the U.S. government to view the National Archives related to the Army of the Potomac and was the first man ever granted such a privilege.

Published in 1877, Taylor’s Four Years with General Lee was the source of dozens of anecdotes about Lee. Drawing upon the authority of his position as an adjutant during the war to bolster his claims, Taylor used official reports and his own recollections to create a picture of a small army struggling mightily against an impossible foe. He argued that Lee had been defeated only by superior numbers and that the general had accomplished great feats in spite of limited resources.

Taylor’s second book, General Lee, His Campaigns in Virginia 1861–1865, with Personal Reminiscences, published in 1906, provided a much richer and more intimate chronicle of the headquarters of the Army of Northern Virginia. This book covered every campaign that General Lee was engaged in, from Cheat Summit Fort to the surrender at Appomattox.

Taylor never violated Lost Cause dogma, but he also never celebrated it. While most Confederate veterans attacked one another, Taylor rose above petty disputes, writing a relatively objective history of the Army of Northern Virginia that dissects the war without any particular agenda. He outlined the fight and the command decisions that affected the battle’s outcome without condemning other officers.

In his superb chapter on Gettysburg, Taylor bluntly tells the reader, “It is not my purpose here to undertake to establish the wisdom of an attack on the enemy’s position on the third day, which General Longstreet contends was opposed by his judgment.” Free of the petty squabbling that Lee so detested among his subordinates, Taylor’s books gives the reader an inside look at the operations of Lee’s headquarters.

Beyond this, Taylor worked on The Southern Historical Society Papers and several Confederate veteran’s organizations, including the Association of the Army of Northern Virginia and the United Confederate Veterans. He also wrote numerous articles about the Civil War, and kept in contact with many Confederate officers.

Late in the 19th century, Taylor was active in the development of the Ocean View area, located along the south shore of the Chesapeake Bay in Norfolk County. The project had been surveyed and laid out before the American Civil War by William Mahone, another of General Lee’s officers.

Served by a narrow gauge railroad from Norfolk, which operated a steam locomotive named the Walter H. Taylor, Ocean View blossomed as both a popular resort area and a streetcar suburb of the City of Norfolk, which annexed the area in 1923.

In April 1907, while Taylor was the attorney for the new Virginian Railway, then under construction, he met the founder Henry Huttleston Rogers and humorist Mark Twain when they arrived in Hampton Roads. They were in Norfolk to attend the Jamestown Exposition, celebrating the founding of Jamestown. According to newspaper reports, Twain drove off with Taylor in an infernal machine, better known as an automobile.

Walter Herron Taylor died of cancer March 1, 1916, in Norfolk at the age of 77, and was buried in Elmwood Cemetery in Norfolk. All four of his sons and three of his sons-in-law were the pallbearers.

Elizabeth Saunders Taylor died four months later.

Taylor is portrayed by Bo Brinkman in the films Gods and Generals and Gettysburg.

SOURCES

Walter H. Taylor

Wikipedia: Walter H. Taylor

HistoryNet.com: Four Years With General Lee