The Woman Who Saved the Brooklyn Bridge

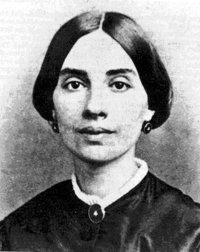

Emily Warren Roebling (1843-1903) was married to Washington Roebling, who was Chief Engineer of the Brooklyn Bridge. After her husband was incapacitated by caisson disease (the bends), Emily helped him complete the building of the bridge. First American woman engineer, one source calls her a prioneering example of independence.

Emily Warren Roebling (1843-1903) was married to Washington Roebling, who was Chief Engineer of the Brooklyn Bridge. After her husband was incapacitated by caisson disease (the bends), Emily helped him complete the building of the bridge. First American woman engineer, one source calls her a prioneering example of independence.

Childhood and Early Years

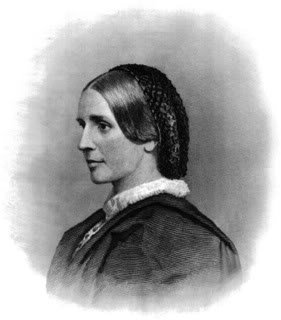

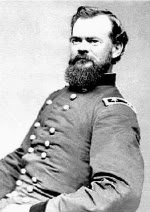

Emily was born into the upper middle class family of Sylvanus and Phebe Warren at Cold Spring, New York on September 23, 1843. She was the second youngest of twelve children. Emily’s interest in pursuing an education was supported by her older brother Gouverneur Warren, future Union general in the Civil War.

In 1864, during the Civil War, Emily visited her brother General Gouverneur Warren, who was then commanding the Fifth Army Corps, at his headquarters. During the visit, she became acquainted with Washington Roebling, the son of John Roebling, a civil engineer serving on General Warren’s staff. Emily and Washington immediately fell in love, and after 11 months of constant correspondence, the two were married on January 18, 1865.

Washington Roebling wrote of his wife Emily in a letter to his sister in 1865:

Some people’s beauty lies not in the features, but in the varied expression that the countenance will assume under the various emotions. She is… a most entertaining talker, which is a mighty good thing you know, I myself being so stupid.

From mid-1865 to 1867, Washington Roebling worked with his father on the Cincinnati-Covington (Ohio-Kentucky) Bridge. In 1867 John Roebling began to work on his latest project: a bridge over New York’s East River between Brooklyn and Manhattan, while Emily and Washington sailed to Europe to study the use of caissons on the bridge. While traveling in Europe, Emily gave birth to the couple’s only child, John A. Roebling II, in November 1867.

The Brooklyn Bridge

After the Roeblings returned to the US in 1868, Washington became assistant engineer on the Brooklyn Bridge. While conducting surveys for the bridge project, John Roebling’s foot was crushed when a ferry pinned it against a piling. After his toes were amputated, he developed a tetanus infection which resulted in his death.

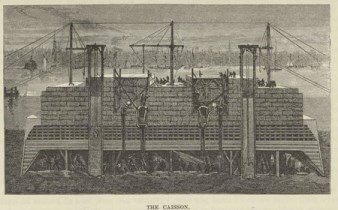

After the tragic death of his father in mid-1869 Washington Roebling was named chief engineer of the Brooklyn Bridge project. He made several important improvements on the bridge construction, and he designed the two large pneumatic caissons that would become the foundations for the two bridge towers.

Construction of the bridge therefore began out of sight, in two huge wooden caissons on the river bed. These large watertight chambers with no bottoms were towed into position and placed on the river bottom. Compressed air was then pumped into the chambers of the caissons to keep water from rushing in, allowing construction work to be done underwater.

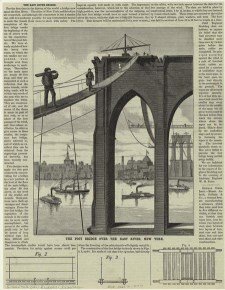

Image: One of the caissons under the Brooklyn Bridge towers

Image: One of the caissons under the Brooklyn Bridge towers

Working inside the caissons was exceedingly difficult. The atmosphere was always misty, and the only illumination was provided by the dim light of gas lamps. Men called sand hogs dug deeper and deeper in the river bed, until they reached solid bedrock. At that point, the digging stopped, the caissons were filled with concrete. Today the Brooklyn caisson sits 44 feet below water level; the caisson on the Manhattan side had to be dug deeper, and is 78 feet below water.

Caisson Disease

Everyone who entered the caissons had to pass through a series of air locks to enter the chamber in which they worked, and the greatest danger was in coming up to the surface too quickly. It was named caisson disease because it afflicted workers when they left the compressed atmosphere of the caisson and rapidly reentered the normal (uncompressed) atmosphere. During the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge, numerous workers were either killed or permanently injured by this disease.

This ailment can produce many symptoms. Nitrogen gas bubbles in the bloodstream and tissue can migrate to any part of the body, and its effects may vary from joint pain and rashes to paralysis and death. Caisson disease can cause neuralgia – sharp, shocking pains that follow the path of a damaged nerve. The release of gas bubbles in tissue can cause distress in breathing or total collapse.

Washington Roebling often entered the caissons on the bottom of the East River to supervise the ongoing work, and one day in the spring of 1872 he came to the surface too quickly and was incapacitated. He recovered for a time, but the illness continued to afflict him so badly that he became bedridden.

Roebling would battle the after-effects of caisson disease and its treatment the rest of his life. He may have had additional afflictions, side effects of treatments, or secondary drug addiction. By the end of 1872 he was no longer able to visit the bridge construction site, but he continued to oversee the Brooklyn Bridge project.

First Woman Engineer

As the only person to visit her husband during his sickness, Emily Warren Roebling relayed information from Washington to his assistants and reported back to him on the progress of the work. She took it upon herself to study the technical issues, learning about strength of materials, stress analysis, cable construction and calculation of catenary curves, and developed an extensive knowledge of the engineering used in bridge building.

Image: Drawing of the completed Brooklyn Bridge

Image: Drawing of the completed Brooklyn Bridge

The design provided three safeguard systems and made it six times stronger than it needed to be. To do this, they had to come up with huge cables needed for a suspension bridge twice the length of any other. They created their own by formulating a process of wrapping steel wire into steel ropes and twisting them into cables over fifteen inches thick.

Husband and wife jointly planned the bridge’s continued construction, while Emily took over many of the chief engineer’s duties, including project management. Every day she went to the site to convey her husband’s instructions to the workers and to answer questions. She carried out all face-to-face interviews with contractors, kept detailed records, and represented her husband at social functions. She eventually became so good at the job that many suspected she was the real intelligence behind the bridge.

Meanwhile Washington Roebling remained in their home in Brooklyn Heights and observed the progress at the bridge through a telescope. David McCullough, author of The Great Bridge: The Epic Story of the Building of the Brooklyn Bridge, remarked that “nowhere in the history of great undertakings is there anything comparable” to Roebling conducting the largest and most difficult engineering project ever “in absentia.”

McCullough also wrote this about the lady engineer overseeing the project:

By and by it was common gossip that hers was the great mind behind the great work and that this, the most monumental engineering triumph of the age, was actually the doing of a woman, which as a general proposition was taken in some quarters to be both preposterous and calamitous. In truth, she had by then a thorough grasp of the engineering involved.

As the project faced delays and cost increases, skepticism mounted that the bridge could be completed under Washington Roebling’s guidance, and it was proposed that he be removed as chief engineer. Emily recorded her husband’s statement, citing the reasons why he should not be displaced.

Emily Roebling delivered her husband’s statement as an address before the American Society of Civil Engineers – a brave move on her part, as women who spoke in public were not often well-received in those days. Fortunately, her remarks were respected and the Roeblings continued to lead the project.

For the next fourteen years, Emily’s dedication to the completion of the Brooklyn Bridge was unyielding. She took over much of the chief engineer’s duties, including day-to-day supervision and project management. Emily and her husband jointly planned the bridge’s continued construction. She dealt with politicians and everyone associated with the work on the bridge to the point that some people believed she was behind the bridge’s design.

As construction on the bridge continued, the caissons were filled with cement, and huge stone towers were built on top of the caissons. These towers rose nearly 300 feet above the water of the East River. In the days before skyscrapers, when most buildings in New York were only two or three stories, that was simply astounding to the general public.

When the towers were completed in early 1877, a narrow footbridge, made of rope and wooden planks, was strung between the top of the towers for the use of the bridge workers, but daring people who obtained special permission could walk across. The walkway swayed in the wind, more than 250 feet above the swirling waters of the East River.

Image: Illustrated magazines published depictions of the Brooklyn Bridge’s temporary wooden footbridge, and the public was riveted.

Image: Illustrated magazines published depictions of the Brooklyn Bridge’s temporary wooden footbridge, and the public was riveted.

In 1882, Washington’s title of chief engineer was again in jeopardy due to his illness. Emily went to meetings of engineers and politicians to defend her husband. To the Roeblings’ relief, the politicians responded well to Emily’s assurances, and Washington was permitted to remain Chief Engineer of the Brooklyn Bridge.

On opening day of the new Brooklyn Bridge, May 24, 1883, Emily Warren Roebling was the first to cross the bridge by carriage. A delegation including the mayor of New York and President Chester A. Arthur walked from the New York end of the bridge to the Brooklyn tower, where they were greeted by a delegation led by Brooklyn’s mayor, Seth Low. Countless spectators watched from both sides of the river that evening as a massive fireworks display lit the sky.

At the opening ceremony, Abram Hewitt, one of Roebling’s competitors said:

The name of Emily Warren Roebling will… be inseparably associated with all that is admirable in human nature and all that is wonderful in the constructive world of art. [This bridge is] …an everlasting monument to the self-sacrificing devotion of a woman and of her capacity for that higher education from which she has been too long disbarred.”

In addition to the bridge itself, there were roadways (one going in each direction) for horse and carriage traffic and railroad tracks which took commuters back and forth between terminals at either end. Elevated above the roadway and railroad tracks was a sturdy pedestrian walkway – no more swaying in the wind. It was estimated that more than 150,000 people crossed the bridge on foot on the first day it was open to the public.

The Manhattan approach to the Brooklyn Bridge was 1,562 feet, and the Brooklyn approach, which began from higher land, was 971 feet. By comparison, the center span of the bridge itself is 1,595 feet across. Counting the approaches, the land spans and the river span, the entire length of the bridge is 5,989 feet, or more than a mile.

The Brooklyn Bridge caused widespread awe and wonder in the general public and the press. One magazine article states:

For the first time in the history of the world, a bridge now spans the East River. The cities of New York and Brooklyn are connected; and although the connection is but a slender one, still it is possible for any venturesome mortal to make the transit from shore to shore with safety.

With the bridge completed, Emily Roebling and her husband moved to Troy, New York, where they lived from 1884 to 1888, while their son John A. Roebling II attended the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. When their son graduated, the Roeblings returned to Trenton, New Jersey in 1892.

In Trenton, they managed the construction of their mansion there. She also assumed an active social life, taking on important roles in the Daughters of the American Revolution, the Huguenot Society, and other civic organizations. She traveled extensively, and served as both a nurse and construction foreman at the Montauk, Long Island camp, which housed soldiers returning from the Spanish-American War.

Image: Emily Warren Roebling Memorial Marker

Today the Brooklyn Bridge holds a plaque dedicated to the memory of Emily, Washington and and John Roebling. It was erected in 1951 by The Brooklyn Engineers Club. The inscription reads:

The Builders of the Bridge

Dedicated to the memory of

Emily Warren Roebling (1843-1903)

Whose faith and courage helped her stricken husband

Col. Washington A. Roebling, C.E. (1837-1926)

Complete the construction of this bridge

From the plans of his father

John A. Roebling, C.E. (1806-1869)

Who gave his life to the bridge.

Back of every great work we can find

The self-sacrificing devotion of a woman.

Late Years

Emily Roebling also continued her education and received a law degree from New York University, and became one of the first female lawyers in New York State. She studied mathematics and science, learned how to build a bridge, and in 1899, she obtained a law degree from New York University at the age of 56. She spent her remaining years with her family and kept socially and mentally active.

Emily Warren Roebling died February 28, 1903 from stomach cancer.

Over the years the bridge has been modernized to accommodate automobiles; the train tracks were eliminated in the late 1940s. The pedestrian walkway still exists, and it remains a popular destination for tourists. Shocking news photos were taken there on September 11, 2001 – the most horrific day in American history – when thousands of people used the walkway to flee lower Manhattan as the World Trade Centers burned and collapsed behind them.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Brooklyn Bridge

Wikipedia: Emily Warren Roebling

Men Labored in Horrendous Conditions in the Caissons Under the Brooklyn Bridge