General Sherman Deported Women from the South

In July 1864, approximately 400 mill workers in Georgia – nearly all women, were taken prisoner by the Union Army. They were then put on trains headed North, and few of them ever made their way back home. They would be referred to as Factory Hands or Roswell Women in the Official Records.

Image: Roswell Mill Women

Backstory

During the summer of 1864, the Union Army under the leadership of General William Tecumseh Sherman advanced toward Atlanta, Georgia. The two armies faced off at the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain (June 27, 1864). Sherman discovered that the Confederate forces were too well entrenched so he cut his losses and continue toward Atlanta. The Chattahoochee River stood in his way.

In the face of superior numbers, CSA General Joseph E. Johnston withdrew his troops across the Chattahoochee, and prepared to defend Atlanta. Sherman then sent Brigadier General Kenner Garrard and his advance Calvary unit on toward Roswell, about 20 miles north of Atlanta, looking for the best place to cross the river.

In the meantime, the Roswell Guard, a local defense unit made up largely of mill workers, were called out three hours before the arrival of Union troops. Confederate troopers collided with Garrard’s advance cavalrymen just outside of town. Overwhelmed and outnumbered, the Confederates raced through Roswell and burned the covered bridge behind them.

The Roswell Mills

Before the Civil War, Roswell was known primarily as the tiny town plantation owners fled to in order to escape coastal Georgia’s brutal summers. After the war began, the two Roswell Cotton Mills and the Ivy Woolen Mill became a thriving textile center. The cotton mills manufactured sheeting, tent canvas and rope, while the woolen mill produced a fine grey-colored cloth used for making uniforms. Many Confederate soldiers marched off to war in Roswell Grey.

The Mill Women

Each of the mills employed hundreds of women and young girls, some of them black. The women often brought their children with them to the mills because they had no one to care for them while they worked. Other residents had fled before the Union soldiers arrived, but the mill women remained on the job, producing materials for the Confederate soldiers.

Everyone except the mill workers had fled the city. The leading families had left for safer places well before the Federal invasion, and arranged for their slaves to be taken away and hidden from advancing Federal troops.

The Occupation

On July 5, 1864, with no way to cross the river, General Kenner Garrard’s cavalry occupied Roswell. With the bridge in flames, Garrard turned his attention to the mills. He was surprised to see a French flag flying over the Ivy Woolen Mill, and investigated further.

A Frenchman named Theophile Roche had been given temporary ownership of the factory a few days earlier. He had hoped that flying a French flag might save the mill, but Garrard discovered that the Confederate symbol (CSA) was stamped on all of the fabric produced at the mills. Angered by the ploy, Garrard ordered the burning of all three mills.

The following day, July 6, 1864, Garrard reported to General Sherman, detailing the destruction of the mills:

Everything is taken out of this country; the grain cut by the rebel soldiers and hauled off. All citizens of property also have left. There were some fine factories here, one woolen factory, capacity 30,000 yards a month, and has furnished up to within a few weeks 15,000 yards per month to the rebel Government… Capacity of cotton factory 216 looms, 191,086 yards per month, and 51,666 pounds of thread, and 4,299 pounds of cotton rope. This was worked exclusively for the rebel Government. The other cotton factory, one mile and a half from town, I have no data concerning. There was six months’ supply of cotton on hand. Over the woolen factory the French flag was flying, but seeing no Federal flag above it I had the building burnt. All are burnt. The cotton factory was worked up to the time of its destruction, some 400 women being employed. There was some cloth which had been made since yesterday morning, which I will save for our hospitals (several thousand yards of cotton cloth), also some rope and thread.

Sherman immediately responded, giving Garrard further instructions, which sounded like a dress rehearsal for the March to the Sea a few months later:

“I had no idea that the factories at Roswell remained in operation, but supposed the machinery had all been removed. Their utter destruction is right and meets my entire approval, and to make the matter complete you will arrest the owners and employees and send them, under guard, charged with treason to Marietta, and I will see as to any man in America hoisting the French flag and then devoting his labor and capital in supplying armies in open hostility to the Government and claiming the benefit of his neutral flag.

Should you, under the impulse of anger, natural at contemplating such perfidy, hang the wretch, I approve the act beforehand… I repeat my orders that you arrest all people, male and female, connected with those factories, no matter what the clamor, and let them foot it, under guard, to Marietta, whence I will send them by [railroad] cars to the North… The poor women will make a howl. Let them take along their children and clothing, providing they have the means of hauling, or you can spare them.

To General Henry Halleck in Washington, Sherman noted that the women were “tainted with treason” and “are as much governed by the rules of war as if in the ranks… The whole region was devoted to manufacturies, but I will destroy every one of them.”

The women and children were given a short time to gather their belongings and then marched out to the Roswell town square where they waited long hours for supply wagons to transport them to Marietta. On their arrival in Marietta, the workers were imprisoned in the abandoned Georgia Military Institute, where they remained for the next week.

The Deportation

From Marietta, the 400 or so Roswell Mill women and children were loaded into boxcars and given several days’ rations, none of them knowing where they were being taken or if they would ever return. They were not given the opportunity to leave messages for their loved ones. By July 15, two trainloads of the refugees had been given nine days’ rations and sent north.

Louisville, Kentucky was the final destination for many of the mill workers. On July 21, the Louisville Daily Journal reported:

The train which arrived from Nashville last evening, brought up from the south 249 women and children, who are sent here by order of General Sherman… Why they should be sent here to be transferred North is more than we can understand.

For a while, the women and children were fed and housed by a Louisville refugee hospital, but they were soon left to find living quarters and employment on their own. Most were illiterate and could not write to their families in Georgia to let them know where they were. Eventually, not knowing if their husbands were alive or dead, many of the women who survived remarried in the North.

Other Roswell women were taken across the Ohio River into Indiana. The women in Indiana struggled from the beginning, taking whatever work they could find. Many were uneducated and knew nothing but mill work. There was very little possibility that they would ever find their way home. Many settled near the river; some resorted to prostitution in order to survive. Some eventually made their way back to Georgia.

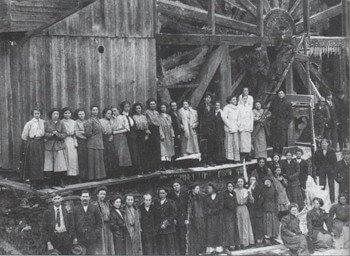

Adeline Bagley Buice

Working at the Roswell Mill while her husband Joshua was serving in the Confederate Army, Adeline Bagley Buice was a very pregnant seamstress when Union forces burned her place of work. Deported north with the other women, she traveled all the way to Chicago. In August, she gave birth to a daughter she named Mary Ann. Over the next five years, Adeline and Mary steadily made their way toward Georgia, mostly on foot.

Image: Adeline Bagley Buice Grave Marker

Image: Adeline Bagley Buice Grave Marker

This simple monument has a bold inscription:

Roswell Mill Worker Caught and Exiled to Chicago by Yankee Army 1864 – Returned on Foot 1869

In the meantime, Joshua Buice returned to Roswell at the end of the war, and discovered that his wife had been deported with the other mill workers. As the years passed and Adeline did not return, he could only assume that she had died, and he remarried. Many of the men who came home from the war to find their wives and families missing followed suit.

There is precious little information about what happened between Adeline and Joshua after she returned to Roswell. However, one source states that Adeline and Joshua had a son they named John Henry in 1867. Could that be possible?

Backlash from the North

The atrocities suffered by these women were noted in some newspapers in the North. The New York Tribune, in reporting the women from Roswell had been loaded into wagons and sent to Marietta, wrote:

Only think of it! Four hundred weeping and terrified Ellens, Susans and Maggies transported, in the springless and seatless army wagons, away from their lovers, and brothers of the sunny south, and all for the offense of weaving tent cloth and spinning stocking yarn.

The article so moved General Grenville M. Dodge, Commander of Sherman’s XVI Corps, that he took $100 from his pocket and instructed his chief surgeon to hire some of the Roswell girls to help care for his sick and wounded.

General Sherman’s actions caused a furor in the North as the people were outraged over the treatment the captives were given. The Patriot and Union, a Pennsylvania newspaper, wrote:

…It is hardly conceivable that an officer bearing a United States commission of Major General should have so far forgotten the commonest dictates of decency and humanity… As to drive four hundred penniless girls hundreds of miles away from their homes and friends to seek livelihood amid strange and hostile people. We repeat our earnest hope that further information may redeem the name of General Sherman and our own from this frightful disgrace.

In 1998 the Roswell Mills Camp No. 1547, Sons of the Confederate Veterans, undertook a project to try to identify the victims and locate their descendants. Intensive advertising and research led to many of the descendants being located, mostly in the North, and most of the mill workers were identified.

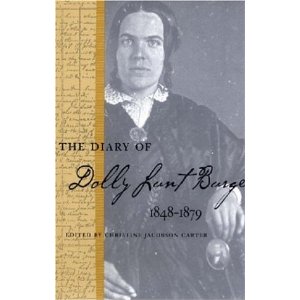

Image: Monument dedicated to the 400 women arrested for treason in July 1864

Image: Monument dedicated to the 400 women arrested for treason in July 1864

Roswell, Georgia

In July 2000, the city of Roswell erected a monument in Mill Village Park to honor the 400 deported Roswell Mill women.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Roswell, Georgia

The Long Walk Home: The Story of Adeline Bagley Buice

I find It horrible that Sherman ordered these women and their children North with no way to care for themselves. Wasn’t it enough that he burned their livlihood when he destroyed their place of work. It sounds like Sherman was bent on revenge. Hopefully he met his God and the revenge was reversed.

From the 1900 US Census, Adeline and Joshua did stay married. Daughter Mary, born in Illinois, survives and marries Ephraim Voylest (Ancestry lists her last name as Voyles). Together they have 9 children.

My husbands family of Peter Goddard and his father in law William Woods . Their whole family was taken and ended up in Hardin Co. Ohio. William was angry that they were made to leave. His one daughter Doxy stayed to help with wounded. She got shot in the shoulder during the attack. Peter’s wife lost twin boys while crossing the Ohio River. They were buried there. That battle was disgraceful as to the conduct and attitude towards these women and I’m from the North.

This is one of many war crimes gen Sherman committed during his travels he was also about as racist as you could be.he was brutal and mean as a snake but he was a soldier and he also knew constantly battling was not working the south might have been losing but they would never give up he knew that too takes my civilians down with the Confederate was his method sometimes I think Hitler copied Sherman since he declared war the same way As for the women he sent north from the mill is one of the biggest tragedies of the civil wat,and sad