One of the Greatest Civil War Love Stories

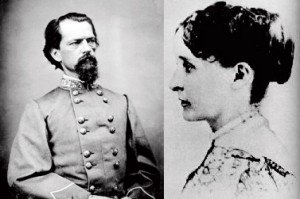

Image: General John Brown Gordon and Fanny Haralson Gordon

Image: General John Brown Gordon and Fanny Haralson Gordon

Married in 1854, John Brown Gordon and Fanny Harralson Gordon shared a loyal and passionate marriage for nearly 50 years. Fanny accompanied her general throughout the Civil War, and is credited with saving his life on more than once.

Marriage and Family

Fanny Haralson met John Brown Gordon after he left the University of Georgia in 1854 to study law in Atlanta. He was admitted to the Bar later that year, and began a law practice with Basil H. Overby and Logan E. Bleckly. Through them, Gordon met Fanny Haralson, who was the younger sister of the wives of both partners. Theirs was a long and happy marriage.

They were married on September 18, 1854, at Myrtle Hill, the Haralson ancestral home near La Grange, Georgia. The marriage lasted until John’s death on January 9, 1904 – almost 50 years. Shortly after the wedding, John and Fanny moved to Atlanta.

Gordon was not happy with his law practice, so he switched to journalism and wrote for a newspaper in Milledgeville – then Georgia’s capital – for a year. He then decided to help his father open a coal mine in northwest Georgia – at the junction of the states of Georgia, Alabama and Tennessee.

The Gordons in the Civil War

When the Civil War erupted in 1861, the Gordons had two small boys and were operating a coal mining company. Fanny and John struggled with their loyalties to family and country. Fanny finally decided that she would accompany John to war. Their boys would be well cared for by relatives, and she would be freed her up for what in her judgment was a higher duty.

When Gordon enlisted in the Confederate Army in 1861, the company of Alabama volunteers he had recruited elected him as their captain. Gordon developed a brilliant military record with the Army of Northern Virginia, fighting in all the major battles, and in many minor ones, in the Eastern Theater. He rose in rank to major general; by the end of the war, he was second in command only to General Robert E. Lee.

Fanny Gordon accompanied her husband throughout the war and saved his life several times. This is an excerpt from Cleveland Civil War Roundtable: John and Fanny – A Love Story:

How then shall we regard the woman who loved him and chose to make her life with him, and shall we be surprised then when we learn that throughout his many campaigns in the war she followed him whenever and wherever she could so that if and when he needed her (and he would!), she would be there? That meant covering a lot of territory, because John was soon all over the landscape with Lee and, later, with [General Jubal] Early. Keeping up with him would have been an arduous task for anyone, but especially for a woman, unless she was an extraordinary woman, which, clearly, she was.

Although Gordon lacked any formal military training, his natural command presence and quick-thinking coolness under fire at the First Battle of Manassas quickly earned him respect and a promotion to colonel in April 1862.

The 30-year-old rising star of the Confederacy was an inspiring leader. Even though he was only a colonel, Gordon assumed command of his brigade off-and-on during the fighting on the Virginia Peninsula during the spring and summer of 1862. He led his command into battle at Seven Pines, riding ramrod straight ahead of his men, bullets piercing his clothes but not his body.

Antietam

On September 17, 1862 as the Battle of Antietam took shape, Colonel John Brown Gordon commanded the 6th Alabama Regiment in the center of General Lee’s lines. At the northern end of the Sunken Road, a dirt road that had been worn down by years of foot and wagon traffic. Gordon described in his memoirs Reminiscences of the Civil War what occurred when General Lee reviewed their lines:

General Lee had decided that the Union commander’s next heavy blow would fall upon our centre, and those of us who held that important position were notified of this conclusion. We were cautioned to be prepared for a determined assault and urged to hold that centre at any sacrifice, as a break at that point would endanger his entire army.

My troops held the most advanced position on this part of the field, and there was no supporting line behind us. It was evident, therefore, that my small force was to receive the first impact of the expected charge and to be subjected to the deadliest fire. To comfort General Lee and General [D.H.] Hill, and especially to make, if possible, my men still more resolute of purpose, I called aloud to these officers as they rode away: “These men are going to stay here, General, till the sun goes down or victory is won.”

But Gordon’s men were greatly outnumbered, and he decided that their only hope for them was to hold their fire until the enemy troops were practically on top of them and then all fire at once. Their first volley knocked down almost the entire Yankee front line. Every line of Union troops were dispersed in the same fashion.

Massive Injuries

The Sunken Road was site to some of the fiercest fighting in the Battle of Antietam. For nearly four hours, Union and Confederate forces fought in this sunken clay road in what would later be named the Battle of Bloody Lane. There are numerous versions of Gordon’s wounding, but in my estimation, there is no better account of the wounds he suffered at Antietam than the one written by Gordon himself in his memoirs:

The first volley from the Union lines in my front sent a ball through the brain of the chivalric Colonel Tew of North Carolina, to whom I was talking, and another ball through the calf of my right leg. On the right and the left my men were falling under the death-dealing crossfire like trees in a hurricane. The persistent Federals, who had lost so heavily from repeated repulses, seemed now determined to kill enough Confederates to make the debits and credits of the battle’s balance sheet more nearly even.

Both sides stood in the open at short range and without the semblance of breastworks, and the firing was doing a deadly work. Higher up in the same leg I was again shot; but still no bone was broken. … When later in the day the third ball pierced my left arm, tearing asunder the tendons and mangling the flesh, they caught sight of the blood running down my fingers, and these devoted and big-hearted men, while still loading their guns, pleaded with me to leave them and go to the rear, pledging me that they would stay there and fight to the last. …

A fourth ball ripped through my shoulder, leaving its base and a wad of clothing in its track. … I had gone but a short distance when I was shot down by a fifth ball, which struck me squarely in the face and passed out, barely missing the jugular vein. I fell forward and lay unconscious with my face in my cap; and it would seem that I might have been smothered by the blood running into my cap from this last wound but for the act of some Yankee, who, as if to save my life, had at a previous hour during the battle, shot a hole through the cap, which let the blood out.

Gordon was carried to a nearby barn where 6th Alabama Assistant Surgeon Thaddeus J. Weatherly dressed his wounds. When Fanny learned her husband had been wounded, she came to the barn. When she saw him, she suppressed a scream as Gordon struggled to joke with her, saying he had been to an Irish wedding.

The last wound Gordon received that day caused his face to turn black and swell so badly that he could barely see. None of this deterred her. She knelt at his side and provided long hours of bedside care and devotion. Fanny Gordon nursed her husband for seven months. She dressed his wounds and fed him brandy and beef tea because his jaw had been wired shut.

When erysipelas, a serious bacterial skin infection, attacked his left arm, doctors told Fanny that daily applications of iodine might cure it. Fanny painted the wound relentlessly with iodine. The infection healed and after many months of care, John was patched together and finally ready to return to the army. For his service at Antietam, John was named brigadier general on November 1, 1862.

Gordon praised his wife’s medical care:

Thenceforward, for the period in which my life hung in the balance, she sat at my bedside, trying to supply concentrated nourishment to sustain me against the constant drainage. … Under God’s providence, I owe my life to her incessant watchfulness night and day, and to her tender nursing through weary weeks and anxious months.

Gordon returned to duty in March 1863 and was given command of a brigade of six Georgia regiments in Early’s division. Fanny was always nearby, but she was sent to the rear before battles. During the Battle of Chancellorsville in May, Gordon launched a successful assault on Marye’s Heights in Fredericksburg, Virginia, and was promoted to brigadier general. When Lee restructured his army soon after, Gordon’s brigade was absorbed into General Richard Ewell‘s Second Corps.

Image: A shadowy photograph of Fanny in old age

Image: A shadowy photograph of Fanny in old age

Overland Campaign

During Grant’s Overland Campaign, Gordon fought at the Battles of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania Court House, Gordon again proved to be a superb leader. Inside the Mule Shoe salient, he skillfully moved his brigades to counter attacks by Colonel Emory Upton on May 10 and General Winfield Scott Hancock on May 12. Fighting continued the following day, but the Confederates held on and established a new defensive line. For his performance at Spotsylvania Court House, Gordon was promoted to major general.

To the Valley

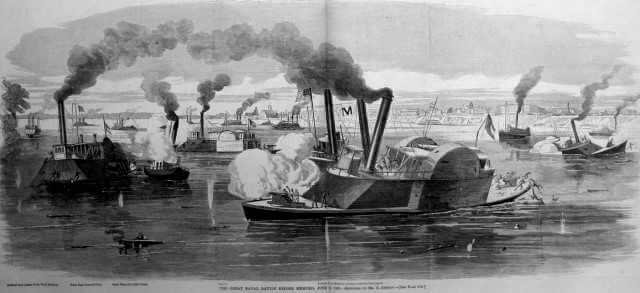

Two months later Gordon fought at the Battle of Monocacy near Frederick, Maryland on a blistering hot July day in 1864. Gordon’s Brigade, now part of Early’s corps, were on a mission to rid the Shenandoah Valley of Union troops, and then cross into Maryland and threaten Washington, DC. They were on their way to do the latter when Union General Lew Wallace forced them into battle at the Monocacy River, 40 miles from the nation’s capital.

Gordon led three brigades of Georgia, Louisiana and Virginia infantry against two brigades of General James Ricketts’ division. The battle ended when Gordon flanked the remnants of Ricketts’ line. But, he wrote, “nearly one-half of my men and large numbers of the Federals fell there.” As Confederate General John C. Breckinridge observed, “Gordon, if you had never made a fight before, this ought to immortalize you!”

Fanny at Winchester

Three weeks later, as Union General Philip Sheridan moved on Winchester, division commanders Gordon and Robert E. Rodes were facing Sheridan’s 30,000 troops with 6,000 men. As they were talking about their next move, Rodes was mortally wounded when a shell fragment struck Rodes in the back of the head, mortally wounding him.

Gordon took over and led both divisions in a charge that pushed the Federals back. The Confederates thought they had won the battle, but Sheridan’s men regrouped and routed the Confederates, even as Fanny Gordon was pleading for them to make a stand. Her husband marveled at her courage:

It requires the direst dangers, especially where those dangers threaten some cause or object around which their affections are entwined, to call out the marvelous courage of women. Under such conditions, they will brave death itself without a quiver. I have seen one of them tested. I saw Mrs. Gordon on the streets of Winchester, under fire, her soul aflame with patriotic ardor, appealing to retreating Confederates to halt and form a new line to resist the Union advance. She was so transported by her patriotic passion that she took no notice of the whizzing shot and shell, and seemed wholly unconscious of her great peril. And yet she will precipitately fly from a bat, and a big black bug would fill her with panic.

General Jubal Early was a bachelor, and he did not approve of wives who followed their husbands to war. He stated, probably in gest, that he wished the Yankees would capture Mrs. Gordon because she always seemed to be around. When she teased him about the remark during a dinner, Early said:

Mrs. Gordon, General Gordon is a better soldier when you are close by him than when you are away, and so hereafter, when I issue orders that officers’ wives must go to the rear, you may know that you are excepted.

On October 19, 1864, Gordon’s Second Corps struck Sheridan’s men, routing two-thirds of them at the Battle of Cedar Creek southwest of Middletown, Virginia.

Early overruled Gordon’s plan for a final assault to sweep the Union VI Corps from the field, saying the Yankees were beaten. But Sheridan re-formed his men and pushed the Confederates from the field – a victory that spelled the end for Confederate campaigning in the Shenandoah Valley.

On to Petersburg

In December 1864, Gordon returned to the Army of Northern Virginia as commander of the Second Corps while Early remained in the Valley. Lee’s army was besieged at Petersburg, Virginia, by General Ulysses S. Grant and the Army of the Potomac. After study and consultation, Lee ordered Gordon to find a spot to attack. He chose Fort Stedman on the Union lines east of Petersburg.

Fanny Gordon continued to follow her husband until late in the war – when she was ill from childbirth and ended up behind enemy lines in Virginia.

For General John Brown Gordon, April 9, 1865 began with leading his weakened and hungry forces into battle at Appomattox Court House, Virginia. He led the last charge of the Army of Northern Virginia, and captured the entrenchments and several pieces of artillery in his front. Hours later, Lee surrendered his weakened and starved army to Grant. Gordon commanded half of the Army of Northern Virginia.

Appomattox Court House

On April 12, 1865, Gordon had the bittersweet honor of leading the Confederate troops in the surrender ceremonies at Appomattox Court House. As the defeated Rebels filed past, Union General Joshua Chamberlain ordered his soldiers to snap their muskets in a show of respect. Gordon instantly wheeled his horse and touched it with a spur so that the horse’s head bowed, and touched his swordpoint to his toe in salute.

Men who served with him, enlisted and officers, sang Gordon’s praises. John W. Worsham of the 21st Virginia Infantry Regiment had previously served under General Thomas J. Stonewall Jackson. Worsham wrote: “Gordon always had something pleasant to say to his men, and I will bear my testimony that he was the most gallant man I ever saw on a battlefield.”

A Sad Tale

… but it must be told. Gordon was a Southerner through and through. After the war, wanting to maintain prominence for Southern whites, Gordon played a major role in the founding of the Ku Klux Klan. He presented the founding documents of the KKK at a convention in Nashville, Tennessee in April 1867, and became the Grand Dragon of the KKK in Georgia. This was a bad choice on his part, but it should not completely overshadow his accomplishments during and after the War.

After the war ended, the Gordons discovered that fighting in North Georgia had damaged their coal mines, and they lacked the money needed to reopen them. They moved to Kirkwood, an Atlanta suburb, where John went into the insurance and publishing businesses.

Gordon served in the U.S. Senate from 1873 to 1880 and from 1891 to 1896, and as Governor of Georgia from 1886 to 1890. In 1889, Gordon became the first president of the United Confederate Veterans. Fanny worked with the Atlanta Ladies’ Memorial Association, the organization which located and buried Confederate soldiers in proper graves.

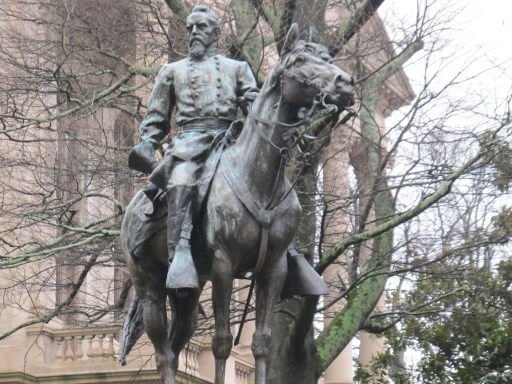

Image: John Brown Gordon Monument with his horse Marye

At the Georgia State Capitol

John Brown Gordon died January 9, 1904 in Miami, Florida at age 71, with Fanny by his side. His death came three months after his memoir, Reminiscences of the Civil War, was published.

President Theodore Roosevelt summed up what many felt by saying:

A more gallant, generous, and fearless gentleman and soldier has not been seen by our country.

Fanny Haralson Gordon lived on, but she was a shadow of her former self. She died April 28, 1931.

SOURCES

Ancestry.com: Rebecca (Fanny) Haralson Gordon

The American Civil War: Colonel John Brown Gordon

Historynet: The 9 Lives of General John Brown Gordon

Cleveland Civil War Roundtable: John and Fanny – A Love Story

Historynet: Shot by Cupid’s Bow – Fanny and John Brown Gordon