Wife of Confederate Major General Henry Heth

Harriet Cary Selden was born on October 13, 1834, in Richmond, Virginia. Henry Heth (pronounced Heeth) was born on December 16, 1825, at Black Heath in Chesterfield County, Virginia. He was the son of Margaret L. Pickett and Navy Captain John Heth, a United States Navy officer in the War of 1812. He was the cousin of General George Pickett. Everyone called young Heth, “Harry,” the name also preferred by his grandfather, American Revolutionary War Colonel, also named Henry Heth, who had established the family in the coal business in the Virginia Colony after emigrating from England in 1759.

Harriet Cary Selden was born on October 13, 1834, in Richmond, Virginia. Henry Heth (pronounced Heeth) was born on December 16, 1825, at Black Heath in Chesterfield County, Virginia. He was the son of Margaret L. Pickett and Navy Captain John Heth, a United States Navy officer in the War of 1812. He was the cousin of General George Pickett. Everyone called young Heth, “Harry,” the name also preferred by his grandfather, American Revolutionary War Colonel, also named Henry Heth, who had established the family in the coal business in the Virginia Colony after emigrating from England in 1759.

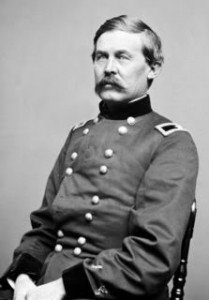

Image: General Henry Heth

Heth refused an appointment to the Naval Academy at Annapolis and went to the United States Military Academy. Heth did not do well at West Point; he graduated in 1847, a disappointing last in his class. Among his classmates were future Civil War generals A.P. Hill and Ambrose Burnside, two of his closest friends at the Academy.

Heth was commissioned a second lieutenant and assigned to the First U.S. Infantry Regiment. Heth struck up a friendship with future Union General Winfield Scott Hancock that survived the Civil War and lasted until Hancock’s death. The two struck up a friendship in Mexico chasing women, with the suave and handsome Hancock having much better luck than Heth.

Heth had become very sick with dysentery, and eventually the army sent him home to Richmond to die. Hancock accompanied him, and his prompt attention saved Heth’s life. Heth got better, and the two went to the Astor Opera House in New York City to see a noted English actor named William McCready. Unfortunately, a dispute broke out and then a riot, resulting in 22 deaths, though Heth and Hancock survived unscathed.

Heth went on to be a dutiful soldier, spending the next fourteen years in the infantry at frontier outposts, slowly compiling a creditable record and rising to the rank of captain of infantry. He was on duty at Fort Atkinson, Fort Kearny and Fort Laramie, taking a conspicuous part in many Indian fights, and promoted to first lieutenant in June 1853, with promotion to adjutant in November 1854, and to captain in March I855. He played a prominent role in the 1855 Battle of Ash Hollow against the Sioux Indians. In 1858, he wrote the first marksmanship manual for the Army.

Harriet Selden married Henry Heth on April 7, 1857, at Norwood in Powhatan County, Virginia. Future Civil War general A.P. Hill served as Heth’s groomsman. The couple had three children: Cary Selden Heth, Henry Heth, Jr., and Ann Randolph Heth.

After the Civil War began, Heth resigned his commission with the U.S. Army on April 25, 1861, and was immediately employed by General Robert E. Lee as Acting Quartermaster General for the Virginia Provisional Army. In those early days of mobilizing for the war, Heth only served as quartermaster until the end of May 1861, but in that short time he made a lasting impression. General Leelooked out for Harry for the rest of the war.

In the careers of the officers of the Army of Northern Virginia, there was no hint of Robert E. Lee’s personal patronage except in the case of Harry Heth. Heth was easy to like for a man such as Lee – he had Lee’s social background, was West Point and Old Army, and of the finest character. Thirty-seven years old, Heth was also personally attractive, socially charming and good looking – of medium height, with lank brown hair and mustache, high cheekbones, strong chin and deep-set eyes.

Heth was strongly opinionated, but one who was able to see his own weaknesses and not take himself too seriously. That General Lee had a strong affection for Heth was obvious to everyone – Heth was the only officer Lee ever called by his first name.

Henry Heth was promoted to Colonel of the 45th Virginia Regiment, and assigned to Western Virginia, where he would serve for the next year. He first served as inspector general under General John B. Floyd, in addition to leading his own regiment. Heth spent the remainder of 1861 in the Kanawha Valley in western Virginia with the 5th and 45th Virginia Infantry regiments.

In January 1862, he was promoted to brigadier general and assigned to the defense of Lewisburg in Western Virginia, gateway to the Kanawha Road through the Allegheny Mountains. There, in a small action on May 23, 1862, his entire command was routed. In a war where officers routinely went to great lengths in their reports to disguise poor performances of their units, Heth, with admirable candor, freely admitted the disgraceful panic and flight of his command in his report of the battle. The embarrassing affair did not affect his reputation.

In the summer of 1862, Heth was assigned to General E. Kirby Smith’s army in East Tennessee. He commanded a division in the Perryville Campaign in the late summer and fall of 1862, but saw no combat in the campaign, because General Braxton Bragg fought the Perryville battle before Kirby Smith’s force arrived. In January 1863, Heth was appointed commander of the Department of East Tennessee.

A month later, Heth was requested by General Lee to join the Army of Northern Virginia. Lee evidently lobbied hard for Heth’s assignment to General Stonewall Jackson‘s corps. Jackson wrote to Lee at one point, “From what you have said respecting General Heth, I have been desirous that he should report for duty.” On March 5, 1863, Heth was given command of Charles Field, who was badly wounded at Second Manassas. Heth stepped in as senior brigadier in the Light Division of General A.P. Hill, his old friend from West Point.

Heth commanded his new brigade for the first time at Chancellorsville in early May 1863. There, determined to show dashing qualities in his first action with the Army of Northern Virginia, he attempted an unsupported counterattack of the Federal Regular Division emerging from the Wilderness on the battle’s first day. He was saved from a nasty repulse by a quick-witted captain.

The next evening, Heth inherited temporary command of the division when Hill was wounded. Heth himself was slightly wounded later in the battle, but he retained command to the end of the fight, prompting a commendation for “heroic conduct” from the acting corps commander, Major General J.E.B. Stuart. His performance standing in for Hill had not been brilliant, but he had at least proven himself steady and reliable while fighting on a scale he had never before experienced.

Following the death of Stonewall Jackson at Chancellorsville, General Lee reorganized his army into three corps, giving A.P. Hill command of the Third Corps on May 24, 1863. After he left Lee’s tent on that day, Hill sat down and wrote a letter concerning the leadership of the divisions in his new command. “Of General Heth,” he wrote, “I have but to say that I consider him a most excellent officer, and gallant soldier, and had he been with the Division through all its hardships, and acquired the confidence of the men, there is no man I had rather see promoted than he.” Having said that, he went on to recommend Dorsey Pender for the post.

Hill then suggested what Lee had in fact already decided to do: combine Archer’s and Heth’s brigades from the Light Division with two other brigades brought up from the Carolinas to form a new divisionto be commanded by Heth. He had so many old friends and had made new ones so quickly with his captivating manner that there was no complaint when Heth was made major general after such a brief time with the Army of Northern Virginia.

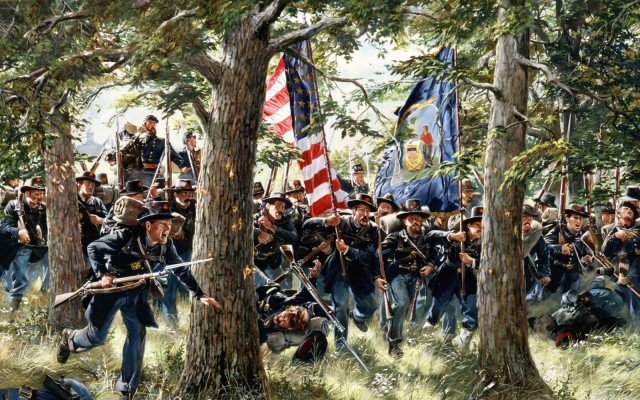

Heth At Gettysburg

After Lee’s army marched into Pennsylvania in the summer of 1863, the inexperienced Heth led A.P. Hill’s Third Corps toward the small Pennsylvania town of Gettysburg. Though General Dorsey Pender and his division were the proper spearhead of Hill’s corps, Heth’s new division was camped closest to the objective, and Heth specifically asked for the assignment. He expected no more fighting than it took to brush aside a cavalry outpost, and he was undoubtedly anxious to justify Lee’s hopes for him, and his new major general’s insignia.

Heth sent James J. Pettigrew’s brigade to Gettysburg the morning of June 30, 1863, as he said in his report, to “search the town for army supplies (shoes especially) and return the same day.” Pettigrew found the town occupied by Union cavalry and returned to Cashtown to report to General Heth.

On the morning of July 1, 1863, by 5 o’clock a.m., Heth was advancing his whole division down the Chambersburg Pike toward Gettysburg, against what he thought was “cavalry, most probably supported by a brigade or two of infantry.” An artillery battalion was in the lead (a careless choice, showing that Heth expected no serious trouble).

At 7:30 am, Heth’s brigades contacted and attacked cavalry outposts under USA Brigadier General John Buford, which had taken up defensive positions, inadvertently starting the Battle of Gettysburg.

General Robert E. Lee had ordered General A.P. Hill to avoid a general engagement with the enemy until Lee could assemble his full army, but Heth’s actions had rendered that order moot. They were engaged and Union reinforcements started arriving quickly. Heth’s poor judgment and recklessness had committed Lee to the battle he expressly wished to avoid.

Heth deployed two of his brigades on the south and north sides of the Pike, both facing east. The artillery were unlimbered on the crest. By that time it was 9:30 am. He gave the battle line the order to advance without bringing up the rest of the division – a costly mistake. By the time Heth’s two brigades had worked their way across the shallow valley in their front and ascended McPherson’s Ridge, they were surprised to meet two brigades of the crack First Division, I Corps of the Army of the Potomac.

In this initial confrontation, which lasted until about 11:30 a.m., one of Heth’s brigades was routed, losing about 600 men, including many captured – among them their leader, Brigadier General James Archer. Davis’s brigade fared no better. After a promising beginning, Brigadier General Joe Davis was thrown back with similar losses, including large numbers captured in the Railroad Cut.

There was a noontime lull in the fighting, while Heth sent back the news to General Hill and reformed his lines on Herr Ridge, bringing up two more brigades – under Brigadier Generals Pettigrew and Brockenbrough – into the fray in the afternoon. He sent his two damaged brigades to the flanks. In the meantime, General Robert Rodes’ division had come up on Oak Hill and attacked the Union defenders on McPherson’s Ridge from the north.

General Lee arrived on the battlefield at about 2:30 pm with General A.P. Hill. Watching Rodes’ attack, Lee saw an opportunity and gave the order for Heth to renew his attack. Heth threw his division forward in a head-on assault in concert with Rodes. Brockenbrough’s Virginians struck the Yankee Bucktail Brigade near the Pike. The Union force was routed, retreating back through town to Cemetery Hill.

Pettigrew’s North Carolinians met the Iron Brigade and drove back them back in some of the fiercest fighting of the war. The Iron Brigade was pushed out of the woods, made three temporary stands in the open ground to the east, but then had to fall back toward Seminary Ridge.

Both sides suffered horribly in the desperate fighting which raged on McPherson’s Ridge over the next hour. Great holes were torn in Heth’s lines, his men fighting and dying at distances of only a few paces from the Union muzzles (one of Pettigrew’s regiments alone lost 687 men), but Heth neglected to ask for support from General Pender’s division when it might have spared his own men much suffering.

The highest ranking casualty of this engagement was General Henry Heth, when he was severely wounded in the head by a musket ball. He was apparently saved from fatal injury by his new felt hat – one of dozens captured in Cashtown a few days earlier. Since the hat was too large for Heth, his quartermaster had stuffed it with wads of newspaper, insuring a snug fit. “I am confidently of the belief that my life was saved by this paper in my hat,” Heth wrote later.

Heth was unconscious for 24 hours; command transferred to Brigadier General James J. Pettigrew. Although Heth insisted groggily on sitting in on Lee’s consultations with his officers the next day, Heth’s part in the battle was over. His brigades had been shattered, nearly half the men in his division killed. Heth did not command his division in the ill-fated July 3 attack on Cemetery Ridge that came to be known as Pickett’s Charge.

Heth was not publicly chided for his recklessness, however, perhaps because such lapses were so prevalent in the Army of Northern Virginia over those three July days, perhaps because of his special relationship with Lee. Heth recovered sufficiently from his wound, however, to resume his command before the army retreated across the Potomac and into Virginia, and the minor engagements of the fall of 1863.

After wintering at Orange Court House, Virginia, Heth commanded the advance of General A.P. Hill’s corps during General Ulysses S. Grant‘s Overland Campaign in the spring and summer of 1864. Heth’s men marched on the Plank Road to resist Grant’s flank movement on May 4, 1864, at the Wilderness. Heth replied for three hours to the attacks of his old friend Union General Winfield Scott Hancock on the Brock Road, and Heth was also distinguished for courageous fighting at the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House on May 10, 11, and 12, 1864.

During the Siege of Petersburg, Heth served on the lines from July 1864 until the evacuation, occupying the extreme right of Lee’s lines during September, October, and November 1864. Heth fought gallantly on the Weldon Railroad August 18, 19, and 20; at Reams Station captured 2,000 men, 9 pieces of artillery and many flags; and in all the struggles on the right.

Heth served ably in all the subsequent battles of the Army of Northern Virginia, but never rose to any feats of greatness. Lee and Hill repeatedly turned to Heth to defend the logistical lifelines that sustained the army against an inexorable Union campaign to cut off their lines of supply, and lastly he commanded at Burgess’ Mill when the Confederate lines were broken.

When General A.P. Hill was killed during the last Union offensive against Petersburg on April 2, 1865, Lee intended to have Heth take command of the Third Corps, but Lee could not easily locate Heth at the time, and assigned what remained of the Third Corps to General James Longstreet.

Heth nonetheless conducted his division on the Confederate retreat west from Petersburg, and surrendered with General Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865.

After the war, Heth gave his attention to mining for a time, worked in the insurance business at Richmond, Virginia, and later served in the U.S. government as a surveyor and in the Office of Indian Affairs. He also assisted the War Department in its efforts to gather material for its Official Records of the Civil War.

Major General Henry Heth died of Bright’s disease at his home in Washington, DC, on September 27, 1899, at the age of 73. He was buried at the Confederacy’s Place of Heroes, Hollywood Cemetery, in Richmond.

Harriet Selden Heth died on December 31, 1907, at Washington, DC, at the age of 73, and was also buried at Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond.

Image: Henry and Harriet Heth Graves

Image: Henry and Harriet Heth Graves

Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond

General Henry Heth was the author of A System of Target Practice (published in 1858) and The Memoirs of Henry Heth (published in 1974). He was portrayed by Warren Burton in the 1993 film Gettysburg, based on Michael Shaara’s novel, The Killer Angels.

SOURCES

Henry Heth

Henry Heth (1825–1899)

Wikipedia: Henry Heth

Heth Renews His Attack

Major General Henry Heth

Henry Heth: Major General

Henry Heth Wounding Tree Stump

Letter from Major-General Henry Heth

The Generals of Gettysburg: The Leaders of America’s Greatest Battle by Larry Tagg. Major General Henry Heth at Gettysburg