Wife of Union General Philip Sheridan

While a bridesmaid at a wedding in Chicago in 1874, Irene Rucker met General Philip Sheridan, who made his headquarters there. For the next few months, he courted her steadily, and contemporaries recalled the hero of the Civil War and “Miss Rucker riding down Wabash avenue in an open carriage.”

While a bridesmaid at a wedding in Chicago in 1874, Irene Rucker met General Philip Sheridan, who made his headquarters there. For the next few months, he courted her steadily, and contemporaries recalled the hero of the Civil War and “Miss Rucker riding down Wabash avenue in an open carriage.”

Irene Sheridan was the daughter of Brigadier General Daniel H. Rucker, Quartermaster General of the US Army, and she spent all her life connected to the military. General Rucker’s first wife, Flora McDonald Coodey, was the daughter of Joseph Coodey, a half-blood Cherokee, and granddaughter of Jane Ross, a sister of the celebrated Cherokee Chief John Ross. Joseph Coodey was a well to do citizen who owned and operated a grist mill on Bayou Menard near the crossing of the old stage coach road between Fort Gibson and Tahlequah, Oklahoma. Flora McDonald Coodney died around 1845-46.

Irene Rucker Sheridan was born in 1856, the daughter of Irene Curtis Rucker, who married the General after his first wife died. Young Irene spent most of her girlhood in Washington, DC, and at various Army posts.

Philip Henry Sheridan was born in Albany, New York, on March 6, 1831, but grew up in Ohio. He attended West Point and, after a one-year suspension for assaulting a fellow cadet with a bayonet. He fell only seven demerits short of being expelled, and finished 34th out of 49. Several other members of his class of 1853 also became well-known, including John Schofield, John Bell Hood, and James McPherson – first in the class of 1853.

An obscure lieutenant serving in Oregon when the Civil War began, Sheridan rose to the command of the Union’s cavalry by the time the Confederacy surrendered. He saw action in Mississippi, Tennessee, Kentucky, and in Virginia, where his campaign through the Shenandoah Valley laid waste to an important source of Confederate supplies.

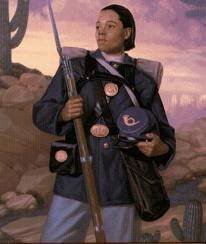

Sheridan started the Civil War as Chief Quartermaster of the Army of Southwest Missouri. Feeling that he would be a better field commander than a support officer, Little Phil, 5′ 5″ tall, persisted until he got an appointment as a colonel with the Second Michigan Volunteer Cavalry. A month later he commanded his first forces in combat.

At the Battle of Booneville, July 1, 1862, he held back several regiments of General James R. Chalmers’ Cavalry. His actions so impressed his superiors that they promoted him to Brigadier General and assigned him command of the 11th Division, Third Corps, Army of the Ohio.

In the spring of 1862, one of his fellow officers gave him the horse that he would ride throughout the war. At the time, the regiment was stationed at Rienzi, Mississippi, and Sheridan named his horse Rienzi. Sheridan was always able to control him by a firm hand and a few words. He was as cool and quiet under fire as any veteran trooper in the Cavalry Corps. At the battle of Cedar Creek, October 19, 1864, the name of the horse was changed to Winchester, the name of the town made famous during Sheridan’s ride through the Shenandoah Valley.

On October 8, 1862, Sheridan again distinguished himself during the Battle of Perryville. He pushed two Arkansas brigades across Bull Run but was ordered back by Third Corps commander, Major General Charles Gilbert. Both sides suffered heavy casualties.

On December 31, 1862, the first day of the Battle of Murfreesboro, Sheridan held back the Confederate advance until his ammunition ran out and he was forced to withdraw. For his actions, he was promoted to Major General, and put in charge of the Second Division, 4th Corps, Army of the Cumberland. In six months, he had risen from captain to major general.

At the Battle of Chickamauga, September 19 and 20, 1863, Sheridan along with the rest of the army was forced to withdraw after two days of heavy losses. At the Battle of Missionary Ridge on November 25, 1863, Sheridan took the initiative and broke through the Confederate lines. General Ulysses S. Grant, newly promoted to be general-in-chief of all the Union armies, decided he wanted Sheridan when he went east.

Image: General Philip Henry Sheridan

Image: General Philip Henry Sheridan

In March, 1864, Grant assigned Sheridan to command the Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac. During the Overland Campaign, Sheridan fought at the Battle of the Wilderness (May 5-7, 1864) and Spotsylvania Court House (May 8-21, 1864). From May 9-24, 1864, Grant sent him on a raid toward Richmond. The raid was less successful than hoped, although his soldiers killed CSA General J.E.B. Stuart at Yellow Tavern (May 11, 1864). Rejoining the Army of the Potomac, Sheridan’s cavalry excelled at Haw’s Shop (May 28, 1864), seized Cold Harbor (June 1-12, 1864) and withstood a number of assaults until reinforced.

All during the war, the Confederacy sent armies out of Virginia through the Shenandoah Valley to threaten Washington, DC, and a raid throughout Maryland and Pennsylvania. CSA General Jubal Early attacked Union forces near Washington and raided several towns in Pennsylvania. In August 1864, General Grant organized the Army of the Shenandoah, and put Sheridan in charge of driving Early out of the Valley and closing it as a route to Washington.

Sheridan went at it with vigor. He beat Early at Third Winchester and Fisher’s Hill. In the final battle, at Cedar Creek, Sheridan rallied the troops who were retreating after a surprise attack – Early was defeated. Sheridan ordered total destruction of the Shenandoah Valley – his troops destroyed crops and livestock, seized stores and equipment, and burned what they couldn’t remove. Sheridan said, “If a crow wants to fly down the Shenandoah, he must carry his provisions with him.”

The destruction presaged the scorched earth tactics of US General William Tecumseh Sherman‘s March to the Sea through Georgia: deny an army a base from which to operate and bring the effects of war home to the population supporting it.

Sheridan again joined the Army of the Potomac at Petersburg in March, 1865. At Waynesboro on March 2, he trapped the remainder of Early’s army and 1500 soldiers surrendered. On April 1, he cut off CSA General Robert E. Lee‘s lines of support at Five Forks, forcing Lee to evacuate Petersburg.

President Abraham Lincoln sent General Grant a telegram on April 7, 1865: “General Sheridan says, ‘If the thing is pressed, I think that Lee will surrender.’ Let the thing be pressed.” Sheridan wrote in his memoirs, “Feeling that the war was nearing its end, I desired my cavalry to be in at the death.”

Sheridan’s finest service of the Civil War was demonstrated during his relentless pursuit of Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, effectively managing the most crucial aspects of the Appomattox Campaign for General Grant. His aggressive and well-executed performance at the Battle of Sayler’s Creek on April 6 effectively sealed the fate of Lee’s army, capturing over 20% of his remaining men.

At Appomattox Court House, April 9, 1865, Sheridan blocked Lee’s escape, forcing him to surrender later that day. After the surrender of Lee in Virginia and of General Joseph E. Johnston in North Carolina, the only significant Confederate field force remaining was in Texas, under General Edmund Kirby Smith.

Sheridan was supposed to lead troops in the Grand Review of the Armies in Washington, DC, but Grant had appointed him commander of the Military District of the Southwest on May 17, 1865, six days before the parade. With orders to defeat General Smith without delay and restore Texas and Louisiana to Union control, Sheridan headed south, but Smith surrendered before Sheridan reached New Orleans.

In March 1867, with Reconstruction barely started, Sheridan was appointed military governor of Texas and Louisiana. He severely limited voter registration for former Confederates, and then required that only registered voters (including black men) be eligible to serve on juries.

An inquiry into the deadly riot of 1866 implicated numerous local officials, and Sheridan dismissed the mayor of New Orleans, the Louisiana attorney general and a district judge. He later removed Louisiana Governor James Wells, accusing him of being “a political trickster and a dishonest man.” He also dismissed Texas Governor James Throckmorton, a former Confederate, for being an “impediment to the reconstruction of the State,” replacing him with the Republican who had lost to him in the previous election.

Sheridan had been feuding with President Andrew Johnson for months over interpretations of the Military Reconstruction Acts and voting rights issues, and within a month of the second firing, the president removed Sheridan, stating to an outraged General Grant that, “His rule has, in fact, been one of absolute tyranny, without references to the principles of our government or the nature of our free institutions.”

Within six months, Sheridan succeeded William Tecumseh Sherman as commander of the Division of the Missouri, which encompassed the entire plains region from the Rocky Mountains to the Mississippi. There he immediately shaped a battle plan to crush Indian resistance on the southern plains. Following the tactics he had employed in Virginia, Sheridan sought to strike directly at the material basis of the Plains Indian nations.

Sheridan believed that attacking the Indians in their encampments during the winter would give him the element of surprise and take advantage of the scarce forage available for Indian mounts. He was unconcerned about the likelihood of high casualties among noncombatants, once remarking, “If a village is attacked and women and children killed, the responsibility is not with the soldiers but with the people whose crimes necessitated the attack.”

The first demonstration of this strategy came in 1868, when three columns of troops under Sheridan converged on what is now northwestern Oklahoma to force the Kiowa, Comanche, Arapaho and Cheyenne onto their reservations. The key engagement in this successful campaign was George Armstrong Custer‘s surprise attack on Black Kettle’s village along the Washita, an attack that came at dawn after a forced march through a snowstorm.

Many historians now regard this victory as a massacre, since Black Kettle was a peaceful chief whose encampment was on reservation soil, but for Sheridan the attack served its purpose, helping to persuade other bands to give up their traditional way of life and move onto the reservations.

In March 1869, after Ulysses S. Grant became president and General Sherman became General of the Army, Sheridan was appointed lieutenant general with headquarters in Chicago. Returning to Chicago, he presided over the Great Chicago Fire of October 7-8, 1871. He brought troops into the city to stop looters and directed fire fighting and reconstruction. Although Sheridan’s personal residence was spared, all of his professional and personal papers were destroyed.

While a bridesmaid at a wedding in Chicago, in 1874, Irene Rucker met General Sheridan, while his headquarters was there. Her father, General Daniel Rucker, Assistant Quartermaster United States Army, was on General Sheridan’s staff.

On June 3, 1875, Irene Rucker married Philip Sheridan at the residence of her parents on Wabash Avenue in Chicago. She was a pretty brunette of 22; he was 44. The bride’s dress was a white grosgrain silk softened by a tulle veil fastened with orange blossoms. The bride’s accessories included a gold necklace with solitaire pendant, diamond solitaire earrings, and gold bracelets, all gifts of the bridegroom. General Sheridan and all the Army Officers appeared in full dress uniform.

After the wedding, the couple moved to Washington, DC, where they lived in a large house at Rhode Island Avenue and Seventeenth street N, bought for them by Chicago citizens who were grateful to General Sheridan for his work following the great Chicago fire in 1871. Irene quickly became one of the most popular members of Washington society, often entertaining as many as 300 callers a day. The Sheridans had four children: Mary, born in 1876; twin daughters, Irene and Louise, in 1877; and Philip, Jr., in 1880.

Sheridan refined his tactic of massive force directed in surprise attacks on Indian encampments, and mounted successful campaigns against the tribes of the southern plains in 1874-1875, and against those of the northern plains in 1876-1877, forcing them onto reservations with the tactics of total war. Although some of his generals in these campaigns, such as Nelson Miles, expressed a soldierly respect for the Indians they were fighting, Sheridan was notorious for his supposed declaration that “the only good Indian is a dead Indian,” which he steadfastly denied saying.

On November 1, 1883, Phil Sheridan succeeded William T. Sherman as Commanding General of the US Army, a position he held until shortly before his death. He was promoted to the rank of General in the United States Army by Act of Congress June 1, 1888, which is equivalent to a four-star general in the modern US Army. This is the nation’s highest military office – which he achieved at the comparatively young age of fifty-two. He was the fourth man in US history to be so honored, the others being Washington, Grant, and Sherman.

In 1887, Sheridan had built a summer cottage in Nonquit, Massachusetts, overlooking Martha’s Vineyard. The following year, he suffered a series of massive heart attacks, two months after sending his memoirs to the publisher. Although only 57 years old, hard living and hard campaigning and a lifelong love of good food and drink had taken their toll. Thin in his youth, he then weighed over 200 pounds.

General Philip Sheridan died August 5, 1888, at their vacation cottage, leaving Irene with four young children. His body was returned to Washington, DC, and lay in state at St. Matthew’s Church until August 11, when he was laid to rest on a hillside facing the capital city near Arlington House, which helped elevate the Arlington National Cemetery to prominence.

General Philip Sheridan’s Personal Memoirs (two volumes) were published soon after his death. Irene never remarried, saying she “would rather be the widow of Phil Sheridan than the wife of any man living.” Curiously, Irene Rucker and his family are never mentioned in his memoirs.

Sheridan’s famous horse Rienzi, renamed Winchester after it carried Sheridan on his desperate ride from there to Cedar Creek, was later stuffed and displayed at the Army museum on Governors Island in New York Harbor. In 1922, the museum was damaged by fire and it was decided that Winchester should be sent to the Smithsonian. The few remaining veterans of the city did not let Sheridan’s war-horse leave without a fitting goodbye. They held a little goodbye ceremony, and the grandson of one of the veterans who attended read Thomas Buchanan Read’s poem, Sheridan’s Ride.

A Time magazine article of May 1930 about Irene Sheridan stated:

Before the Senate last week came bill No. 319 to increase the pension of Irene Rucker Sheridan. Her present pension: $2500 per year. Proposed the bill: $5000. The Senate pensions committee recommendation: $3600. Up rose Colorado’s Senator Phipps, a man of wealth and generosity, and said:

“The action of the committee reducing the amount is a mistake. Mrs. Sheridan is the widow of General Phil Sheridan who had a wonderful record. Mrs. Sheridan is well along in years and in all human probability, she will not enjoy the advantages of a pension for many years to come. I ask that the bill be approved in the original amount.”

The Senate snubbed its pensions committee, and unanimously voted the widow of one of the nation’s five generals $5000 per year. The bill must be acted upon by the House before she gets the money. Today Mrs. Sheridan, now living in retirement in Washington, is almost 80.

Since General Sheridan’s death in 1888, Irene had divided her time between her home in Washington and the summer home in New England. She had not been active in Washington affairs since about the time of World War I. No one connected the wrinkled little old lady who gazed at Phil Sheridan’s statue near her home with the great beauty of the 1870s.

Irene Rucker Sheridan died at her home at 2211 Massachusetts Avenue NW, Washington, DC, in 1936, at the age of 83. Funeral services were held in St. Matthew’s Church, the same church in which Cardinal Gibbons performed the last rites for General Sheridan. Irene was survived by her three daughters, Mary, Irene, and Louise Sheridan, and two grandchildren, Carolina and Philip Sheridan III.

Image: Fort Sheridan Monument

Image: Fort Sheridan Monument

Sheridan astride his horse Rienzi

Battle of Five Forks April, 1865

SOURCES

Widow’s Pension

Philip H. Sheridan

Scrappy Phil Sheridan

General Phil Sheridan

About Famous People

Irene Rucker Sheridan

General Daniel Henry Rucker

Philip Henry Sheridan 1831 – 1888

Personal Memoirs of P. H. Sheridan

Is Rose Clare or Clare family any relation to Irene Rucker’s family or Phillip Sheridan II ‘s wife , mother of Carolina and Phillip III Sheridan.