Civilian at the Battle of Averasboro

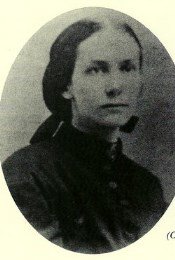

Janie Smith lived on a huge plantation near Averasboro, North Carolina. She was eighteen years old when General William Tecumseh Sherman plowed through the Carolinas with his scorched-earth policy, hoping to end the civil war that had dragged on for four long years. Janie lived with her parents and her nine brothers and two unmarried sisters; eight of her brothers were serving in the Confederate Army.

Janie Smith lived on a huge plantation near Averasboro, North Carolina. She was eighteen years old when General William Tecumseh Sherman plowed through the Carolinas with his scorched-earth policy, hoping to end the civil war that had dragged on for four long years. Janie lived with her parents and her nine brothers and two unmarried sisters; eight of her brothers were serving in the Confederate Army.

Following the Battle of Averasboro, North Carolina – March 15 and 16, 1865 – eighteen-year-old Janie Smith (1846-1882) wrote an insightful letter on scraps of wallpaper (due to the paper shortage during the war) about the battle and her family’s experiences to her friend Janie Robeson in Bladen County.

Janie was the daughter of Farquhard and Sarah Slocumb Grady Smith. There were three homesteads on the large plantation where Janie lived in 1865, owned by three brothers, one of them her father. The William Smith House, a fourteen-room Federal period house, was occupied by Janie’s widowed aunt and four daughters. Her Uncle John and his family resided at Oak Grove.

Janie lived in the plantation house named Lebanon with her parents and her nine brothers and two unmarried sisters. Eight of her brothers served in the Confederate Army. Lebanon was used as a field hospital during and after the battle, where mostly Confederate wounded were treated. After the battle, Union General Henry Slocum briefly made Lebanon his headquarters.

Battle of Averasboro

On March 8, 1865, the Union Army crossed into eastern North Carolina, en route to the town of Goldsboro, where General Sherman planned to unite with two additional Federal units that were marching in from the coast.

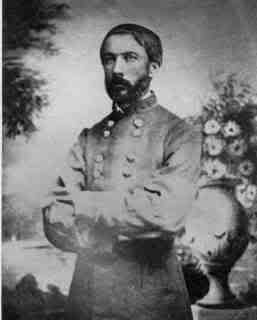

General Robert E. Lee called upon his old friend, General Joseph. E. Johnston, to gather what forces he could find and oppose the Union advance. Lee feared that Sherman would occupy Raleigh and take possession of the rail lines, thus cutting off supplies to the Army of Northern Virginia that was still entrenched around Petersburg.

On March 15, south of Averasboro, where the Cape Fear and the Black Rivers are only two miles apart, Confederate General William J. Hardee’s forces moved to block the Federal advance onto the Raleigh Plank Road, placing his troops across the main roads. There was heavy skirmishing throughout the day.

Union cavalry under General Hugh Judson Kilpatrick contacted some of Hardee’s men along the old Plank Road northeast of Fayetteville. Kilpatrick could not punch through, so he regrouped and waited until March 16 to renew the attack.

On March 16, 1865, General Sherman’s army encountered its most significant resistance as it tore through the Carolinas on its way to join General Ulysses S. Grant at Petersburg, Virginia. By 9:00 a.m. on March 16, Sherman had everything in place to brush Hardee’s forces aside.

Confederate troops were deployed just north of the Oak Grove house. The Yankees attacked and the Rebel line was sent reeling backward. Three field pieces were captured, and two of them were turned and fired at their former owners as the Rebels scampered toward the rear. When they tried again, the Yankees still could not break the Confederate lines until two divisions of General Slocum’s infantry arrived.

Confederate General Joseph Wheeler’s cavalry arrived in the nick of time and extended Hardee’s line to the bluffs overlooking the Cape Fear River, and they were able to hold on until nightfall. But they were badly outnumbered, and General Hardee retired to the town of Smithfield that night. The action resulted in a standoff. Hardee lost some 500 men; the Union army, almost 700.

Janie Smith’s letter provides a remarkable glimpse of the battle and its aftermath:

Where Home Used to be

April 12, 1865

The battle commenced on the 15th of March at Uncle John’s. The family [Uncle John’s family] were ordered from home, stayed in the trenches all day when late in the evening they came to us, wet, muddy and hungry. Their house was penetrated by a great many shells and balls, but was not burned and the Yankees used it for a hospital, they spared it, but everything was taken and the furniture destroyed. The girls did not have a change of clothing.

The Confederates used Lebanon as a field hospital, and Janie was shocked and horrified at seeing battlefield wounds for the first time in her life.

…oh it makes me shudder when I think of the awful sights I witnessed that morning. Ambulance after ambulance drove up with our wounded. One half of the house was prepared for the soldiers, but owing to the close proximity of the enemy they only sent in the sick, but every barn and out house was filled and under every shed and tree the tables were carried for amputating the limbs.

I just felt like my heart would break when I would see our brave men rushing into the battle and then coming back so mangled. The scene beggars description, the blood lay in puddles in the grove, the groans of the dying and the complaints of those undergoing amputation was horrible, the painful impression has seared my very heart. I can never forget it.

The family rolled bandages and sent food to the sick and wounded until they were ordered to leave their home because of the close proximity of the fighting. Janie found it difficult to leave the poor wounded soldiers behind:

But orders from headquarters must be obeyed and to the woods we went. I never expected to see the dear old homestead again, but thank heaven, I am living comfortably in it again.

General Wheeler had tea with the Smiths at Lebanon after the battle was over – about two o’clock on the morning of March 17th – but their visit did not last long:

…about four o’clock the Yankees came charging, yelling and howling. I stood on the piazza and saw the charge made, but as calm as I am now, though I was all prepared for the rascals, our soldiers having given us a detailed account of their habits. The pailing [fences] did not hinder them at all. They just knocked down all such like mad cattle.

Right into the house, breaking open bureau drawers of all kinds faster than I could unlock. They cursed us for having hid everything and made bold threats if certain things were not brought to light, but all to no effect. They took Pa’s hat and stuck him pretty badly with a bayonet to make him disclose something, but you know they were fooling with the wrong man…

Every nook and corner of the premises was searched and the things that they didn’t use were burned or torn into strings. No house except the blacksmith shop was burned, but into the flames they threw every tool, plow etc., that was on the place. The house was so crowded all day that we could scarcely move…

All of Uncle John’s family were here and we lived for three days on four quarts of meal [corn meal] which Aunt Eliza begged from a Yank. Didn’t pretend to sift it, baked up in our room where fifteen of us had to stay.

When and how we slept, I don’t know. I was too angry to eat or sleep either and I let the scoundrels know it whenever one had the impudence to speak to me. Gen. Slocum with two other hyenas of his rank, rode up with his body-guard and introduced themselves with great pomp, but I never noticed them at all…

They got all of my stockings and some of our collars and handkerchiefs. If I ever see a Yankee woman, I intend to whip her and take the clothes off of her very back. We would have been better prepared for the thieves but had to spend the day before our troops left in a ravine as the battle was fought so near the house, so we lost a whole day hiding.

The Yankees left fifty wounded Rebels at Uncle John’s house, and Janie and the girls nursed them as best they could:

I felt my poverty keenly when I went down there and couldn’t even give them a piece of bread. But, however, Pa had the scattering corn picked up and ground, which we divided with them, and as soon as the Country around learned their condition, delicacies of all kinds were sent in.

I can dress amputated limbs now and do most anything in the way of nursing the wounded soldiers. We have had nurses and surgeons from Raleigh for a week or two. I am really attached to the patients of the hospital and feel so sad and lonely now that so many have left and died.

It grieves me to see them buried without coffins, but it is impossible to get them now. I have two graves in my charge to keep fresh flowers on… Lieutenant Laborde, the son of Dr. Laborde of Columbia College… had passed through the fight untouched, and while sitting on the fence of our avenue resting… a stray ball pierced his head.

His with three other Confederate graves are the only ones near the house. But the yard and garden at Uncle John’s, the cottage and Aunt Mary’s are used for Yankee grave yards, and they are buried so shallow that the places are extremely offensive. The Yankees stayed here for only one day…

Janie closed her letter with some news of the family’s current condition:

As you suppose, we had little corn left at the plantation and a cow or two. I am not afraid of perishing though the prospects for it are very bright. When our army invade the North, I want them to carry the torch in one hand, the sword in the other… I know you think this a very unbecoming sentiment, but I believe it is our only policy now.

After the Battle of Averasboro, General William Hardee headed north toward a rendezvous with General Joseph Johnston’s army. After news of General Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, a Confederate surrender between General Joseph E. Johnston and General William Tecumseh Sherman was negotiated six weeks later at Bennett Place, a farm in north-central North Carolina.

Generals Johnston and Sherman signed the final papers of surrender on April 26, 1865, disbanding all active Confederate forces in North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia and Florida – a total of 89,270 soldiers, the largest troop surrender of the Civil War.

SOURCES

Averasboro Plantations

Averasboro: Eyewitness to the Battle

Confederates Swept Aside at the Battle of Averasboro