Activist in the Abolitionist and Women’s Rights Movements

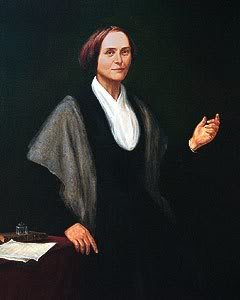

Image: Family of Slaves

Image: Family of Slaves

Washington, DC, 1861

Josephine Sophia White Griffing was a social reform activist who campaigned for the abolition of slavery and women’s rights. In 1864, she moved to our nation’s capital to help the newly freed slaves who were streaming into the capital by the thousands. Griffing worked primarily as an agent for the Freedmen’s Bureau in Washington, DC.

Early Years

Josephine White was born December 18, 1814 in Hebron, Connecticut into a prominent New England family. Her father Joseph White Jr. served as a representative in the state legislature; her mother was sister of portrait artist Samuel Lovett Waldo. Little is known of Josephine’s childhood, and there are no known images of her.

In 1835, at age twenty, Josephine married Charles Griffing. In 1842 they moved to recently-settled town of Litchfield in northeastern Ohio, where they had five daughters, three of whom – Emma, Helen, and Josephine Cora – survived to adulthood.

Abolitionist Movement

While living in Litchfield, Ohio, Josephine Griffing became involved with some of the radical organizations that were thriving in northeastern Ohio. By 1849, Josephine was an active member of the Western Anti-Slavery Society. By 1851 she was a traveling agent for that organization, preaching “no union with slaveholders” throughout the West, and becoming one of the most prolific anti-slavery speakers in the region.

She wrote articles for the Anti-Slavery Bugle in Salem, Ohio, and opened up their home as a stop on the Underground Railroad. Throughout the 1850s she preached against the government in Ohio, Indiana and Michigan. Remarks she made in 1858 illustrate how committed she was to freedom for the slaves:

Impatient are we? There is a power which crushes our brothers into dust, and mocks at God’s authority. And we are impatient because we wish to have the rights of the slaves restored, because we wish them to be developed by intellectual culture, because we would have them enjoy the social relations, would restore the husband and wife to each other, give back the babes to the mother. …

Women’s National Loyal League

During the Civil War, Griffing served as a western agent for the Women’s National Loyal League, an organization founded by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, after President Abraham Lincoln gave his Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. The League’s purpose was to campaign for an amendment to the U.S. Constitution that would abolish slavery throughout the country. Griffing joined the League as a lecturing agent.

In the largest drive in the nation’s history up to that time, the Women’s National Loyal League collected nearly 400,000 signatures on petitions to abolish slavery; Griffing convinced hundreds of women to sign. Abolitionist Charles Sumner presented those petitions to the U.S. Congress. On December 18, 1865, Secretary of State William Seward proclaimed the adoption of the Thirteenth Amendment, which ended slavery in the United States.

The League was the first national women’s political organization in the United States and it came at the perfect time – when women’s activism was beginning to shift from a loosely structured effort to a highly organized women’s rights movement. The League also contributed to the development of a new generation of leaders and activists who would propel the movement forward. Instead of a broad spectrum of goals, they soon focused solely on securing the right to vote for women.

Image: Envisioning Emancipation

Multiracial emancipated slaves, 1863

Temple University Libraries

Freedmen’s Aid Movement

In May 1864, Josephine Griffing visited Washington to petition Congress to allow Northern and Western women reponsibility for the care and education of freedwomen and children. Petitioning was one of the only political outlets for women, as they were denied the right to vote. Griffing beseeched Congress to give governmental approval to women’s work in the freedmen’s aid movement. She envisioned women acting as ministers, teachers, doctors, and providing for the general welfare of former slaves.

While in Washington, Josephine Griffing’s attention was drawn to the thousands of suffering freedmen who had fled to the seat of government, hoping to be sheltered and fed. However, authorities could not have anticipated the huge influx of these helpless freedpeople to the capital. Griffing wrote to William Lloyd Garrison:

I have seen them in every condition of want – from their first landing, sitting in the sand, with their babies hovering round them, without shelter or bread, through all the varieties and grades, up to comparative comfort and independence. I conclude, without hesitation, that with assistance from Government, in protecting them against the controland the frauds of any and all who wich to usurp authority over them in regard to their homes, labor and children, this independence is their proper status of rights and duties, and the only one that will give them satisfaction, and secure their confidence in our Government and people. Indeed, I am astonished at the self-reliance and thrift they possess under these insurmountable difficulties.

Griffing was determined to help the freedpeople establish a new independent life. She moved to Washington, DC in 1864 with her three daughters, while her husband remained in Ohio. From 1864 onward, her aims centered around the freedmen in Washington.

To these former slaves, freedom meant economic independence through land ownership and freedom from white control. They wanted to reunite with relatives, legalize marriages, and enjoy freedom of movement for the first time in their lives. They wanted to establish their own churches, schools and other institutions, and to gain access to justice in Southern society, while Southern whites sought to retain control of blacks.

Created by an act of Congress on March 3, 1865, the Freedmen’s Bureau was a temporary agency embedded within the War Department. Its purpose was to provide “supervision and management of all abandoned lands, and control of all subjects relating to refugees and freedmen from rebel states.” The act gave the Bureau power to issue provisions, clothing, fuel, temporary shelter and other assistance to freedmen.

Josephine Griffing became an agent for the National Freedmen’s Relief Association of the District of Columbia, a private freedmen’s relief agency of which there were many. She established two industrial schools for freedwomen and taught them skills with which they could earn a living, such as sewing. She also instilled in freedwomen white middle class values. In Griffing’s words:

The Industrial School furnishes an opportunity for instruction in social science and domestic relations, as well as the higher forms of Industry, and a marked change is observable in personal tidiness, good manners, and in the control and government of young children – whom some of the mothers are obliged to bring with them to the Rooms.

While in Washington, Griffing also used lobbied Congressmen for more direct aid for the formerly enslaved people of Washington. Through her friendship with Radical Republican members of Congress, such as Benjamin Wade and Charles Sumner, Griffing helped establish the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands, better known as the Freedmen’s Bureau. In June 1865, as reward for her work, Commissioner Oliver O. Howard appointed her assistant commissioner of the Bureau of Washington, DC.

However, she and the male leaders of the organization often disagreed over how to help the former slaves in Washington. Griffing argued that they required direct aid: food, clothing and fuel. This aid, according to Griffing, was necessary for them to become financially stable, and once that occurred they could find jobs and support themselves. However, many men in freedmen’s aid organizations encouraged self-reliance so that freedpeople could find jobs and survive financially without assistance.

Griffing spoke out about the lack of direct aid, claiming that 20,000 freedpeople in Washington, DC were suffering for lack of rations and supplies. The agents of the Bureau denied her statement, despite the evidence supporting her argument. By November 1865, Commissioner Howard had revoked Griffing’s appointment due to conflicts with male members.

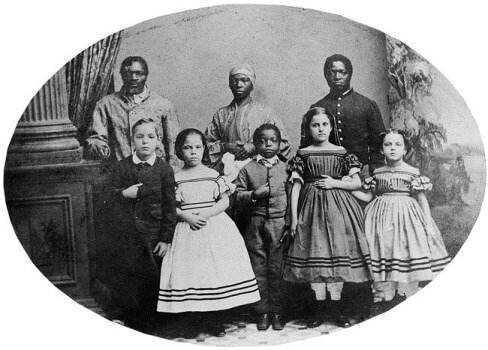

Image: On to Liberty

Image: On to Liberty

By Theodor Kaufmann

Retreating Confederate troops often took male slaves with them, leaving behind the women and children.

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Even with this setback, Griffing continued to help better the lives of freedpeople. She worked with her government contacts to help them find jobs in the north, and sometimes traveled with them to make sure they arrived safely. The Freedmen’s Bureau worked with Griffing on this project, providing barracks in Rhode Island, offices in New York City, and funds for rent and other necessary expenses.

By 1867, Griffing was working for the Freedmen’s Bureau once again, as an agent for the Capitol Hill and Navy Yard districts. During her time there, she fought for increased aid and continued her efforts to find employment for African Americans in the north. Her associates in the federal government and in private organizations helped her procure aid for the destitute of Washington, DC through the National Freedmen’s Aid Association of the District of Columbia until her death.

This excerpt from Genealogy of the Waldo Family (1902) sums up Griffing’s work on behalf of the freedpeople:

Mrs. Griffing was a woman of more than ordinary intellectual gifts and literary attachments. She, for many years, addressed public meetings upon the subject of the liberation of the slaves, and in 1865, at the close of the war, removed to Washington, DC, devoting the remainder of her life to the care and interests of the freed people. Her labors in Washington consisted in securing the first food, shelter and clothing for the many thousands of freed people who flocked to Washington after the emancipation, the greater number of whom were from the adjoining states, although, later, many came from the states further south. Through the assistance of Secretary Edwin M. Stanton, she secured condemned barracks for shelter, army blankets and army rations and wood for the old and sick.

Later, in connection with the Freedmen’s Bureau, of which she was the originator, she added to her work a bureau of correspondence with church and aid societies throughout New England, securing from them clothing and homes and, from the government, transportation for between eight and ten thousand able-bodied men and women. Soup houses for the old, sick, children and the needy unemployed, were kept open for several years, as were also industrial schools, where women and children were taught. Mrs. Griffing continued in this work until the autumn of 1871, when her health gave way under her untiring and ceaseless labors.

Women’s Rights Movement

In addition to her work for the freedpeople, Griffing was a women’s rights activist. In the 1850s, Griffing became involved with women’s rights organizations, making contact with women who would inspire her to fight for the rights of women as well as African Americans. Throughout the 1850s, Griffing joined various feminist organizations, such as the Ohio Women’s Rights Association, which she became the president of in 1853. She was also active in the temperance movement that was popular amongst many feminist activists.

Former slave and prominent abolitionist Frederick Douglass wrote a letter to Griffing September 27, 1868:

My Dear Friend:

… The right of woman to vote is as sacred in my judgment as that of man, and I am quite willing at any time to hold up both hands in favor of this right. It does not however follow that I can come to Washington or go elsewhere to deliver lectures upon this special subject. I am now devoting myself to a cause not more sacred, certainly more urgent, because it is one of life and death to the long-enslaved people of this country, and this is: negro suffrage. While the negro is mobbed, beaten, shot, stabbed, hanged, burnt and is the target of all that is malignant in the North and all that is murderous in the South, his claims may be preferred by me without exposing in any wise myself to the imputation of narrowness or meanness toward the cause of women.As you very well know, woman has a thousand ways to attach herself to the governing power of the land and already exerts an honorable influence on the course of legislation. She is the victim of abuses, to be sure, but it cannot be pretended I think that her cause is as urgent as that of ours. I never suspected you of sympathizing with Miss [Susan B.] Anthony and Mrs. [Elizabeth Cady] Stanton in their course. Their principle is: that no negro shall be enfranchised while woman is not. Now, considering that white men have been enfranchised always, and colored men have not, the conduct of tbese white women, whose husbands, fathers and brothers are voters, does not seem generous.

Very truly yours,

Fredk Douglass

While living in Washington, DC, Griffing maintained her dedication to women’s rights and the cause of suffrage. In 1866 she helped found the American Equal Rights Association, whose purpose was to promote equality and suffrage for all people, no matter their race or sex; she also served as its first vice-president. Griffing became president of District of Columbia Woman Suffrage Association in 1867, where she helped guide suffrage activities in Washington, DC. In 1869, along with other prominent reformers, Griffing joined the National Woman Suffrage Association and acted as its corresponding secretary.

Josephine Sophia White Griffing died of consumption (tuberculosis) February 18, 1872, at age 57.

SOURCES

Freedmen’s Bureau

Wikipedia: Josephine Sophia White Griffing

Britannica: Josephine Sophia White Griffing

Angel of Mercy in Washington: Josephine Griffing and the Freedmen, 1864-1872 – PDF