Wife of Confederate General Robert Toombs

Early Years

Julia Ann Dubose was born May 15, 1813, in Lincoln County, Georgia. Her husband, Robert Toombs was born near Washington, Georgia, and the couple made their home in a stately mansion there for the rest of their lives. Robert was the first Secretary of State for the Confederate States of America and fought for the South as a general in the Civil War.

Robert Toombs entered Franklin College at the University of Georgia in Athens when he was fourteen years old; he was expelled for bad behavior in 1827. He then enrolled at Union College in Schenectady, New York, where he graduated in 1828 with a Bachelor of Arts degree. The following year, Toombs began studying law at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. In March 1830, he passed the bar in Elbert County, Georgia.

Marriage and Family

In November 1830, Julia Ann DuBose married her childhood sweetheart Robert Toombs, with whom she had three children. Their first child, a son named Lawrence Catlett Toombs, died in childhood. A daughter named Mary Louisa lived long enough to marry but died in February 1855. Sallie, their youngest child, married General Dudley McIver DuBose, who served with her father during the Civil War. The couple had four children, but Sallie died October 27, 1866.

Robert Toombs in Politics

From 1830 to 1837, Toombs practiced law as a circuit lawyer in several Georgia counties. During those years he met many of the men who would become prominent political figures in Georgia: Charles Jenkins, Joseph Henry Lumpkin, William Dawson, Howell Cobb, and his good friend Alexander Stephens. Toombs friendship with Stephens forged a powerful bond. Both men became Whigs, and after the Whig Party dissolved, helped create the Constitutional Union Party in the early 1850s.

From 1837 to 1843, Toombs practiced law and served in the General Assembly in Milledgeville. He gradually became involved in national politics and became a U.S. Congressman in the 29th Congress in December 1845. On March 4, 1853, Toombs began his career as a U.S. Senator.

From 1853 to 1861 Toombs served in the U.S. Senate, only reluctantly joining the Democratic Party when lack of interest among other states doomed the Constitutional Union Party. His political opinions were clear: he was adamantly pro-slavery and pro-states’ rights. He developed a reputation for speaking his mind and was often criticized.

On December 22, 1860, soon after the election of Abraham Lincoln, Toombs sent a telegram to Georgia stating that “secession by the 4th of March next should be thundered forth from the ballot-box by the united voice of Georgia.” He delivered a farewell address in the Senate January 7, 1861 and returned to Georgia, where he led the fight for secession against his friend Stephens.

Toombs and the Civil War

Toombs had ambitions of becoming president of the Confederacy and resented Jefferson Davis when he was appointed to that position. Toombs reluctantly accepted a position as Secretary of State in Davis’ cabinet. One of his first acts was to send commissioners to Washington to see Union Secretary of State William Seward and attempt to establish diplomatic relations with the United States.

Seward’s aide quietly explained that Secretary Seward could not see them because President Lincoln had determined that there was no nation called the Confederate States of America. After three days the commissioners left. Toombs passed this on to President Jefferson Davis but advised him to wait while they made other attempts.

Toombs and other Southern leaders believed that the United States and the Confederacy could peacefully coexist. However, Davis and his advisors were restless. They took a vote and then ordered General P.G.T. Beauregard to evict the Union soldiers from Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, and so the war began.

Toombs was already frustrated with Davis and his supporters who refused to agree that the Confederacy should ship every bale of cotton it could find to Europe for arms. When Davis ordered an embargo on all shipments of cotton to England and France to pressure those countries to recognize the Confederacy, Toombs was incensed.

Toombs in the Confederate Army

After serving only five months as Secretary of State, he resigned to join the Army of Northern Virginia. He received a commission as brigadier general on July 19, 1861, and served in that position through the Peninsula Campaign, Seven Days Battles and Northern Virginia Campaign.

At the Battle of Malvern Hill (July 1, 1862), Toombs’ brigade lost one-third of its men. General Daniel Harvey Hill witnessed Toombs’ poor performance and sharply reprimanded Toombs, accusing him of cowardice. The arrogant Toombs challenged Hill to a duel, but Hill declined, saying, “when we have a country to defend and enemies to fight, [a duel] would be highly improper …”

President Davis issued an order (August 18, 1862) for the arrest of Toombs for insubordination. He did not rejoin his brigade until August 29, 1862, and his unit was transferred to the corps of General James Longstreet at the Second Battle of Bull Run.

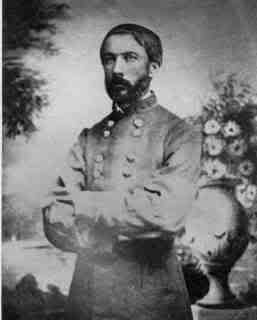

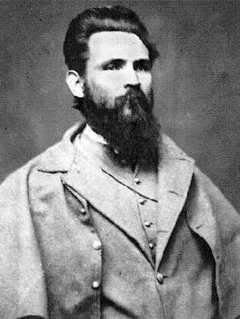

Image: Robert Toombs

Image: Robert Toombs

Toombs’ gallantry in guarding the bridge on Antietam Creek with only 400 men during the Battle of Antietam (September 15, 1862) received special mention in General Robert E. Lee‘s report and the highest commendation from General Longstreet. Toombs received a severe wound to his hand at Antietam and recovered at home in Georgia.

Toombs resigned his commission in the army in March 1863 because President Davis did not promote him to major general for his service at Antietam though his superior officers and a member of the Cabinet recommended him for that rank.

Toombs returned to his home in Georgia; he briefly returned to active service as divisional adjutant and inspector-general of the Georgia Militia during Union General William Tecumseh Sherman‘s Atlanta Campaign and the siege of Savannah in 1864. Fortunately, the Union Army bypassed Toomb’s plantation and left the family fortune intact.

Toombs and Alexander Stephens became close advisors to Georgia Governor Joseph Brown. Stephens had already become disgusted with the government in Richmond and resigned his position as Vice President of the Confederacy.

In April 1865, Brown and Toombs were dining together when news came that Lee had surrendered. A few days later Lincoln was assassinated. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton sent Union troops to arrest Jefferson Davis, Alexander Stephens, Judah P. Benjamin, Robert Toombs, and several other prominent Confederates as conspirators in Lincoln’s murder.

Jefferson Davis met with his Confederate Cabinet for the last time on May 5, 1865, in Washington, Georgia – where Toombs lived – and the Confederate Government was officially dissolved. The meeting took place at the Heard house, with fourteen officials present. Toombs was not invited.

Davis and the other Confederate officials were long gone when a man on horseback rode up to the Toombs house and threw a bag containing five thousand dollars in specie (money in the form of coins rather than notes) in the yard and rode away. There was no message with the money, but it was apparently meant to help Toombs escape from the Union soldiers who had been ordered to arrest him.

On the Run

Union soldiers arrested Jefferson Davis at Irwinville, Georgia, May 10; Stephens at his home in Crawfordville, Georgia, May 12; Union troops appeared at the Toombs home and demanded to see him, May 14. While Julia kept them occupied he escaped out the back to the servants’ quarters, where he mounted a horse and rode away.

After Toombs had fled, the Federal soldiers threatened to burn down the house, believing he might still be hidden there, but Julia sent for the fearless Baptist preacher Henry Allen Tupper, who convinced them that Toombs had escaped. Julia and her daughter were ordered to leave the house but were later permitted to return.

Toombs retreated into the wilds of Georgia and went into hiding with friends. He was hidden for a time in Columbus, Georgia, by novelist Augusta Jane Evans, who later gained fame as the author of St. Elmo and other popular romances.

In the fall of 1865, he traveled to Alabama, where he took a boat to New Orleans. On November 4, he was in Cuba and soon on his way to Europe. In July 1866, Toombs was living comfortably in Paris. Julia Toombs joined him but returned to the United States in December of that year after the death of their only surviving daughter.

Letter from Robert in Paris to Julia Toombs

Paris, Sunday morning, December 23, 1866

My Dear Julia,

I felt so badly yesterday that I did not begin my letter to you. The night you left I returned to the room and did not go to sleep until after two o’clock. I felt so sad at parting with you, and could not help thinking of what a long dreary trip you had that night. I went early next morning to the steam packet [ship] officer to learn what I could about the departure of the steamer from Cadiz in order to telegraph you, but still they had not heard further inquiry. …My mind is made up … to sail the first of January unless more than I now know prevents me. I shall [take] a long journey of five thousand miles from here to Havana and do not know that I shall meet a human being to whom I am known. But if I keep well, I shall not mind that especially as I am homeward bound, for although my hearthstone is desolate, and clouds and darkness hover over the little remnant that is left of us, and upon all of our poor friends and countrymen, yet when you get home, Washington [Georgia] will contain nearly all that is dear to me in this world. …

I am still in and have not gone out to take my walk. It is cold cloudy and chilly and dismal weather, and but little inviting out of doors, but I think it is necessary to go out! My cold continues to improve and I think I should soon get well if the weather was at all good, but it seems impossible to improve. Such weather I hear you have had two bad days for the ocean, I count them as they go, anxious that they may pass away quickly until you get off the sea. …

Late Years

Robert Toombs returned to the United States in January 1867. As things settled down, he and Julia returned to their home in Washington, Georgia. In an April 1867 letter to his friend General John C. Breckinridge, Toombs lamented that upon his return:

Everything looked much worse than I expected, changes had been rapid and radical, the spirit of the great body of the people wholly broken, bankruptcy and ruin widespread throughout the land, the presence of physical wants absorbing the time and thoughts of all the people, and the best and truest people in utter despair at the prospect before them.

The state of Georgia was in chaos, and the courts were in the hands of hostile and unqualified outsiders. Outraged, Toombs struck fear into the judges by lecturing to them on the fine points of the law. He won case after case in the Georgia Supreme Court and the U.S. Supreme Court, and gradually the people reclaimed their state. By 1872 Toombs and Stephens were again the two most powerful men in Georgia.

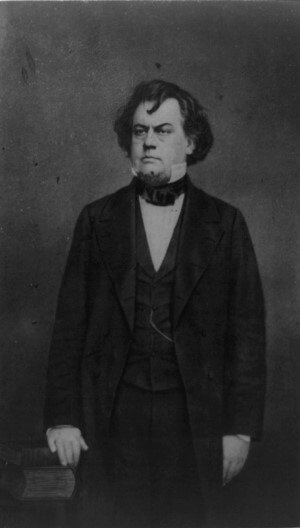

Image: Robert and Julia Dubose Toombs House

Image: Robert and Julia Dubose Toombs House

Washington, Georgia

Between 1867 and 1877, Toombs practiced law in Washington, Georgia with his son-in-law and acquired a considerable fortune. And though he remained primarily in the South, he maintained his national reputation. Robert Toombs refused to request a pardon from Congress, and he never regained his American citizenship.

He was a delegate to the Georgia state constitutional convention of 1877. When they lacked funds to continue their sessions, he provided the needed funds. In December 1877, as a new constitution was adopted, Toombs abundant energy began to wane.

In 1880 Robert and Julia Toombs celebrated their golden wedding anniversary, with children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren present.

The year 1883 was traumatic for Robert Toombs. His lifelong friend and political comrade Alexander Stephens died suddenly on March 4, after serving briefly as Georgia’s governor. Toombs gave the eulogy at the funeral and wept openly. Julia Dubose Toombs died September 4, 1883 at the age of 70. These deaths devastated the aging Toombs, and he descended into depression and self-neglect.

Robert Toombs died December 15, 1885 at the age of 75, and was buried in Rest Haven Cemetery east of town. His grave is marked by a monument that bears only his name.

From the New York Times:

General Robert Toombs died this morning at 6 o’clock. He was stricken with paralysis about three months ago and had since been confined to his room, during which time his mind had been more or less clouded.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Robert Toombs

New Georgia Encyclopedia: Robert Toombs

Digital Library of Georgia: Letter from Paris