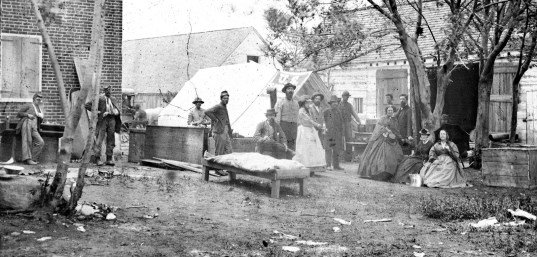

Civil War Nurse

At the beginning of the Civil War, the United States Government was not prepared to offer its soldiers adequate medical care. To fill that need, they created the United States Sanitary Commission on June 18, 1861, to support sick and wounded soldiers of the U.S. Army during the American Civil War. It operated across the North, raised its own funds, enlisted thousands of volunteers and was run by Frederick Law Olmsted.

At the beginning of the Civil War, the United States Government was not prepared to offer its soldiers adequate medical care. To fill that need, they created the United States Sanitary Commission on June 18, 1861, to support sick and wounded soldiers of the U.S. Army during the American Civil War. It operated across the North, raised its own funds, enlisted thousands of volunteers and was run by Frederick Law Olmsted.

The Peninsula Campaign of 1862 lasted nine weeks, and inflicted a terrible cost in lives. During that campaign, Katharine Prescott Wormeley, Georgeanna Woolsey, and Eliza Woolsey Howland served as Union nurses. Working on board Sanitary Commission’s hospital transport ships, these three members of prominent Northern families wrote about their experiences in great detail.

Katharine wrote about her patients’ sufferings, the government’s failure to provide enough supplies for the sick and wounded, and her colleagues. She realized that history was unfolding before her, and carefully described such important events as President Abraham Lincoln‘s July 1862 visit to General George B. McClellan at Harrison’s Landing, Virginia, relating every detail.

These excerpts from a letter Katharine wrote to her mother tell us of the difficulties she suffered.

DEAR MOTHER, Yesterday was a hard day, and not a very useful one. The result is that I am a little befogged this morning—deaf, drowsy, and dull. Five hundred men came down last night, out of the regimental hospitals on the right. Our gentlemen were up all night. I was safe in my berth; but Georgy [Georgeanna Woolsey] was in the tent till 3 a.m., though she had been up all the night before.

Mr. Olmsted has just been, full of brightness, to tell me that everything is arranged satisfactorily, and to read me the signed agreement.

The Commission is to take:

1. All badly wounded men, all amputations and compound fractures of the lower extremities, and all other cases which ought not to travel at first (say five hundred—a large estimate), and keep them on board the Knickerbocker and the St. Mark [hospital ships] in the river until they can be moved. It engages to spend a sum not exceeding ten thousand dollars on the means of carrying out this first item.2. It agrees to receive at Fortress Monroe three thousand other bad cases able to bear transportation, whenever a battle occurs; twelve days of it, and transport them to New York, Washington or elsewhere.

Thus, you see, the Commission gains the certainty that the worst cases and the greatest suffering shall be under its own eye and care. The rest—the slightly wounded, or those so wounded as to be able to help themselves—are the ones that are left to the Government.

This enables us to contemplate a great battle with less of a nightmare feeling than we have had while there was nothing to expect but a repetition of past scenes. We feel that something is impending; the clearing out of the hospitals, the arrangements thus decisively made for the wounded, all seem to point to a coming emergency. Oh! Can we help dreading it!

General Van Vliet has just been here—a jolly old gentleman, with his shock of yellow-white hair, and his nice, old-fashioned politesse for “the ladies.” We fire a volley of questions at him. First, and before all else, “How is the General!?” (meaning General McClellan.) “Ho! He’s well; quite got over that fever of yours—what do you call it, typhoid?”

Then we try to get out of him some information about the state of affairs. He said he dined at General Porter’s headquarters with several of the corps commanders yesterday, and it was universally agreed that General Porter’s position was not tenable any longer; that our line was far too long (I told you that our right was stretched out to touch McDowell).

“Well,” says the General, “Porter is in what you may call a deadlock – can’t get across the river; there’s a battery. What they’ll do will be to try and turn our flank. Perhaps they’ll do it; perhaps not.”

“And we?” We cried.

“Oh, you!” he said, with his jolly laugh, “you’ll have to cut and run as best you can, and we’ll go into Richmond.”

Captain Sawtelle sent me a present of mint to-day (his orderly could not restrain a smile as he give it to me), and the Captain came just now with an eye, I fear, to that improper thing called a “mint-julep.” You may think it very vulgar, but let me tell you it is very good; and you would think so too if you had been up all night, with the thermometer at 90 degrees.

Georgy is flitting about, putting things to rights (or wrongs) with as much energy as if she had not been up two nights. She has hunted me into the smallest corner of the cabin, while she dusts and decorates the rest. Her activity is a never-ending marvel to me.

I saw her to-day spring from the ground to the floor of a freight-car, with a can of beef-tea in one hand, her flask in the other, and a row of tin cups tied round her waist. Our precious flasks! They do us good service at every turn. We wear them slung over our shoulders by a bit of ribbon or an end of rope.

If, in the “long hereafter of song,” some poet should undertake to immortalize us, he’ll do it thus, if he’s an honest man and sticks to truth:

A lady with a flask shall stand,

Beef-tea and punch in either hand,

Heroic mass of mud

And dirt and stains and blood!This matter of dirt and stains is becoming very serious. My dresses are in such a state that I loathe them, and myself in them. From chin to belt they are yellow with lemon-juice, sticky with sugar, greasy with beef-tea, and pasted with milk-porridge. Farther down, I dare not inquire into them. Somebody said the other day that he wished to kiss the hem of my garment. I thought of the condition of that article, and shuddered.

“Georgy,” I said the other day, “what am I to do? I can’t put on that dress again, and the other is a great deal worse.”

“I know what I shall do”, says Georgy, who is never at a loss, and suggests the wildest things in the calmest way: “Dr. Agnew has some flannel shirts, he is going back to New York, and can’t want them. I shall get him to give me one.”

Accordingly Santa Georgeanna has appeared in an easy and graceful costume, looking especially feminine. I took the hint and have followed suit in a flannel shirt from the hospital supplies; and now, having tasted the sweets of that easy garment, we shall dread civilization if we have to part with what we call our “Agnews.”

Good-bye! I have so many letters to write that sometimes I feel as if I could not write another word. I have twelve lying by me now, ready to go off—soldiers’ letters and answers to the friends of the dead.

We receive such pathetic, noble letters from the parents and friends of those who have died in our care, and to whom it is a part of our duty to write. They will never cease to be a sad and tender memory to us. The mothers’ are the most noble and unselfish; the wives’ the most pathetic—so painfully full of personal feeling.

Katharine also served at a hospital on the mainland. The headquarters were known to them as White House, from a small abandoned plantation house on the river. George Washington had lived there after his marriage to Martha. The wounded were brought there by rail and by wagon through the forest.

How these wealthy, refined women who came from a life of ease and gentility ever made the transition to such scenes of horror and death is a complete mystery to me. But there is ample evidence that they did. Maybe it was in the difficulty of the work that they found fulfillment.

Katharine wrote

We all know in our hearts that it is thorough enjoyment to be here. It is life, in short; and we wouldn’t be anywhere else for anything in the world.