First Lady and Wife of Union General Rutherford B. Hayes

Circa 1877

Lucy Webb Hayes (1831-1889) was First Lady of the United States and the wife of President Rutherford B. Hayes, but prior to his presidency, Hayes was a general in the Union Army during the Civil War. Lucy’s kindness and great moral courage contributed greatly to her husband’s successful military and political careers.

Early Years

Lucille Webb, born August 28, 1831, was the daughter of Dr. James Webb and Maria Cook Webb of Chillicothe, Ohio. Though he was originally from Kentucky, Dr. Webb and his family were highly opposed to slavery. After inheriting several slaves from his aunt, he returned to his family home in Kentucky to free them, then worked tirelessly to care for his family there and the slaves who caught the dreaded disease during a cholera epidemic.

Despite his efforts, Dr. Webb lost his parents and a brother in the epidemic, and eventually lost his own life to cholera when Lucy was two years old. When a family friend encouraged Maria Webb to sell the slaves after her husband’s death, she was adamant in her belief that she would “take in washing” to support her family before selling slaves.

In 1844, when Lucy was 12, Maria Webb took her sons to Delaware, Ohio, to enroll in the new Ohio Wesleyan University. Although women were not allowed to study at Wesleyan, Lucy was permitted to attend classes in the preparatory department and earned a few college credits.

Rutherford Birchard Hayes was born in Delaware, Ohio, on October 4, 1822, the son of Rutherford Hayes and Sophia Birchard. Hayes’s father died ten weeks before his son’s birth. Sophia took charge of the family, bringing up Hayes and his sister Fanny, the only two of her four children to survive to adulthood.

Sophia’s younger brother, Sardis Birchard, lived with the family for a time and became a father figure to him, contributing to his education. After Rutherford B. Hayes earned a law degree from Harvard University in 1845, he practiced in Fremont, Ohio. At age 15, Lucy met Hayes while he was visiting relatives in Delaware.

In 1847, when Lucy was 16, Mrs. Webb enrolled her daughter in one of the few colleges in the U.S. that granted degrees to women, Cincinnati Wesleyan Female College. Lucy excelled there and graduated with a liberal arts degree in 1850, very well educated for a young lady of her day.

After Hayes began a new law practice in Cincinnati in 1850, Lucy met him again when they were members of a wedding party. At the reception, Hayes gave Lucy a gold ring – a prize in his piece of wedding cake. When the two were later married, Lucy gave that gold ring back to Rutherford; he wore it for the rest of his life.

Though he was nine years older than she, the two began dating seriously, and he proposed in June 1851. Hayes’ mother, a family friend, had long encouraged a match between the two, being especially drawn to Lucy Webb’s moral and religious character.

Marriage and Family

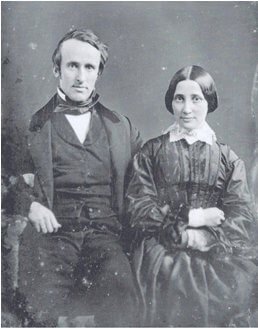

Lucy Webb married Rutherford Hayes December 30, 1852, at her mother’s home in Cincinnati. After the wedding, the couple honeymooned at the home of the groom’s sister and brother-in-law in Columbus, Ohio. The newly married couple lived with Lucy’s mother before buying a home in Cincinnati.

Over twenty years Lucy bore eight children, five of whom lived to maturity: Birchard Austin (1853-1926), Webb Cook (1856-1934), Rutherford Platt (1858-1927), Joseph Thompson (1861-1863), George Crook (1864-1866), Frances “Fanny” (1867-1950), Scott Russell (1871-1923) and Manning Force (1873-1874).

Lucy and Rutherford Hayes were true partners, respecting each other’s values and goals. While practicing law in Cincinnati, Hayes was influenced by Lucy’s anti-slavery sentiments and defended runaway slaves who had crossed the Ohio River.

Lucy hoped that the 1856 Republican presidential candidate John C. Fremont would win the election, and that his colorful wife Jessie Benton Fremont would be First Lady. “Lucy takes it to heart a good deal that Jessie is not to be mistress of the White House,” Hayes wrote at the time. Four years later, Hayes and Lucy were part of a Cincinnati welcoming committee when president-elect Abraham Lincoln came through their city on the way to his Inauguration in 1861.

Hayes in the Civil War

Although neither Hayes had believed war was necessary to end slavery, once the Civil War began Lucy Hayes encouraged her husband to join the Union Army. She lamented that women had not been in a regiment at Fort Sumter, for they would not have surrendered. “It is a hard thing to be a woman,” she wrote, “and witness so much and yet not do any thing.”

Hayes enlisted as a major in the Twenty-third Ohio Volunteer Infantry, though he was almost 40 years old with three small sons. Lucy’s brother Joe also joined the regiment as surgeon. As often as was possible and safe, Lucy visited Hayes in the field, sometimes camping there with her mother and children, helping her brother care for the sick and wounded and winning the affectionate name of “Mother Lucy” from the men.

In September 1862, Hayes was hit in the left arm with a musket ball, Hayes continued to lead his men despite the serious and painful injury, until his men insisted upon carrying him from the field. Lucy’s brother dressed his wound in the field hospital, probably saving his arm from amputation. Lucy went to Maryland, and helped nurse him back to help.

During the war years, Lucy Hayes lost two sons before their second birthday. Joseph Thompson Hayes, born December 21, 1861, died June 24, 1863, while visiting his father’s military encampment near Charleston, West Virginia. Lucy also took in two wounded Union soldiers, and took care of her mother and her mother-in-law, both of whom died in the fall of 1866.

In August, 1864, political supporters in Cincinnati nominated Hayes for Congress. He answered the plea to mount a campaign with: “An officer fit for duty who at this crisis would abandon his post to electioneer for a seat in Congress ought to be scalped.” But he won the election anyway.

However, Hayes remained in the Union Army until May of 1865, after the South surrendered and President Lincoln was assassinated. Although Lucy and the children did not live in Washington while Hayes was in Congress, she visited him often and sat in the gallery of the House to listen to debates. In her letters to him, she wrote that she missed being able to talk politics with him.

While serving his second term in Congress, Hayes was nominated for governor of Ohio by the Republican Party. While he was campaigning, Lucy gave birth to their only daughter. Hayes was elected governor of Ohio in November 1867, but the two Ohio Congressional houses both had Democratic majorities.

With not much hope of passing controversial legislation, he focused on overdue reform of state institutions. Lucy often accompanied him on visits to prisons, correctional institutions for boys and girls and hospitals for the mentally ill, deaf and mute. Lucy was particularly satisfied in establishing an orphanage for children of Civil War veterans.

During Hayes’ two terms as governor, Lucy began her role as hostess, entertaining and lodging friends and political visitors in their rented houses near the Capitol. She gave birth to their sixth son during this time. In 1871, Hayes chose not to run for a third term.

In the spring of 1873, the family moved to Fremont, Ohio, into the home at Spiegel Grove, which Hayes’ Uncle Sardis had built with them in mind. In August, Lucy gave birth to their eighth and final baby, another son – just weeks before she turned 47 years old. Unfortunately, this son did not survive past the age of two.

Image: Spiegel Grove

Image: Spiegel Grove

The Hayes Home in Fremont, Ohio

In 1875, leaders of the Republican Party convinced Hayes to run for an unprecedented third term as governor. During this term he was nominated for President at the Republican convention in June 1876. At that time, custom decreed that other people do the talking for the nominated candidate. During this campaign, Lucy became a prime subject of many newspaper articles, the first time the press had focused on the candidate’s wife.

The election was extremely close and had to be decided through a special Electoral Commission. Lucy’s confidence in Hayes helped him through this tense difficulty – which was not concluded until March 2, 1877, when Congress declared Rutherford B. Hayes as President.

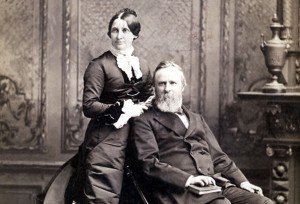

Lucy Hayes as First Lady

There was no inaugural ball in 1877 – when Hayes and Lucy left Ohio for Washington, the outcome of the election was still in doubt. In black dress and black bonnet, Mrs. Hayes stood out the next day on the Inaugural stand, while the new president took the oath of office.

With sons Birchard and Rutherford in college, Hayes and Lucy moved into the White House with six-year-old Scott, nine-year-old Fanny and 21-year-old Webb (who served as his father’s personal secretary). Presidential wives did not have staffs then, so Lucy invited nieces, cousins and daughters of friends to help her with social duties.

Although Lucy was referred to as the “first lady of the land,” it was not the first time a president’s wife was titled as such in the press, as has been widely written. Mary Todd Lincoln was called First Lady in numerous publications, as was Harriet Lane, the niece and hostess of bachelor president James Buchanan.

With her popularity in the press and the fact that she was the first First Lady to have graduated with a college degree, there were high expectations for and pressures placed upon Lucy Hayes during her tenure, most especially from women activists for temperance reform and women’s suffrage.

On the suffrage issue, Lucy ultimately agreed with her husband that women were not yet educated enough to be able to vote intelligently. She resisted joining any public activities that might adversely affect her husband’s political career. She did, however, help to place two women in federal position, one at the Agriculture Department, another at the Patent Office.

Lucy contributed generously to Washington charities, and often sent servants on nightly errands delivering a note and money to someone in need. Lucy also started what has become a tradition: the Easter egg roll. When children were banned from rolling eggs on the Capitol grounds, she invited them to use the White House lawn on the Monday after Easter.

During their stay at the White House, the Hayeses had bathrooms with running water installed and a crude wall telephone added. With a renovating appropriation delayed (due to strained relations with Congress), Lucy scoured the cellar and attic, finding and restoring furniture.

Lucy Hayes was particularly pursued by the Women’s Christian Temperance Union for her national profile but the group’s efforts to enlist her as a leader failed. The incident that sparked the national association of the issue with her was the decision to ban all alcoholic beverages from all entertainment at the White House.

It was actually the President who made the decision. “Water flowed like wine,” joked Congressman James A. Garfield, who would succeed Hayes as president. A teetotaler since her youth, the First Lady supported her husband on the issue, and was nicknamed “Lemonade Lucy.”

As popular a figure as she was, Lucy Hayes was no more beloved than in the community of the severely poor in Washington, who lived in slum areas. Whenever she learned of a family or individual in dire need, she freely gave money from her own account. In January of 1880 alone, the President and First Lady donated nearly $1000, an enormous amount of money at the time.

Her great interest in American history inspired the First Lady to initiate several history-related efforts. She prompted the President to force the continued work on the Washington Monument that had begun in 1848 but had come to a standstill, and commissioned an Ohio artist to paint a full-length portrait of Martha Washington to hang opposite that of George Washington.

Among her children, relatives and friends, Lucy Hayes was known as a warm, charitable woman of humility. She played the piano and the guitar, and also used the newly installed telephone in the mansion. On numerous occasions, the First Lady invited African American musical groups to perform in the White House.

Late Years

Rutherford and Lucy Hayes celebrated their 25th wedding anniversary on December 30, 1877, by renewing their vows at a White House ceremony before many of the same guests who had attended the original nuptials in Cincinnati. Afterwards, they hosted a reception for friends and family.

When he had accepted the presidency, Hayes said he would only serve one term and he kept his word. And, for as much as she enjoyed Washington, Lucy was also ready to leave. They returned to Spiegel Grove in March 1881.

There, Lucy continued to devote herself to charitable activities: joining the Woman’s Relief Corps, teaching a Sunday School class, attending reunions of the Twenty-third Ohio Volunteer Infantry and continuing her work for better prison conditions and veterans’ treatment.

On a summer afternoon, while sewing beside her bedroom bay window and watching Scott and Fanny and their friends playing tennis, Lucy suffered a severe stroke.

Lucy Webb Hayes died in her sleep on June 25, 1889, at age 57. Upon her death, flags across the United States were lowered to half-staff.

Rutherford Hayes was grief-stricken; he had lost his partner in all aspects of his life. On his forty-eighth birthday, he had written to Lucy: “My life with you has been so happy – so successful – so beyond reasonable anticipations, that I think of you with a loving gratitude that I do not know how to express.” Daughter Fanny became her father’s constant companion.

Rutherford B. Hayes died January 17, 1893, at the age of 70. He and Lucy are buried together at Spiegel Grove.

In 1912, son Webb Cook Hayes deeded Spiegel Grove to the state of Ohio, including his father’s library collection of 12,000 books, and began building a museum on the property. In 1916, he opened the first presidential library and museum in the United States. In the late 1960s, Lucy’s birthplace was restored and opened to the public as the Lucy Webb Hayes Heritage Center in Chillicothe, Ohio.

SOURCES

Lucy Hayes Heritage Center

Wikipedia: Lucy Webb Hayes

Wikipedia: Rutherford B. Hayes