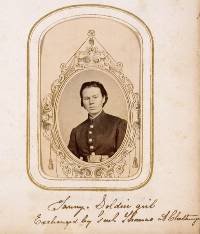

Civil War Nurse from Illinois

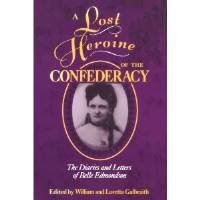

Belle Reynolds followed her husband to war, and ended up serving on the hospital ships at Pittsburg Landing, Tennessee during the Battle of Shiloh, where she was under fire several times. Reynolds recorded her experiences during the war in a diary.

Belle Reynolds followed her husband to war, and ended up serving on the hospital ships at Pittsburg Landing, Tennessee during the Battle of Shiloh, where she was under fire several times. Reynolds recorded her experiences during the war in a diary.

Belle (Arabella) Macomber was born on October 20, 1840 in Shelbourne Falls, Massachusetts. Her father was a well-known lawyer. As a child she heard stories of fugitive slaves from her family and friends.

In April 1860, Belle married William Reynolds, a druggist in Peoria, Illinois. On their first anniversary, they were in church when a messenger brought news of the attack on Fort Sumter. As soon as the news broke, William immediately enlisted in the Union Army and became a lieutenant in the 17th Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment.

On August 20, 1861, Belle joined her husband in camp at Bird’s Point, Missouri. She was one of several women who followed the unit and traveled with their husbands. From then until the end of the war, she kept a diary of her army life and adventures.

Throughout the fall and winter of 1861-1862, Belle traveled with the regiment. Sometimes she marched in the ranks with the soldiers, carrying a musket on her shoulder. They camped along the Mississippi River in southern Missouri, and it was a romantic period for the recently married couple.

At daybreak on Sunday, April 6, 1862, a sudden attack caught Union troops off guard at Pittsburg Landing (Shiloh), Tennessee. Belle and a companion she called Mrs. N. were sitting at a campfire cooking breakfast when they heard gunfire, but they were not alarmed. They thought it was just the pickets firing their muskets to make sure their gunpowder was still dry.

Belle reported her experiences when the Union camps were overrun by the Rebels:

At sunrise we heard the roll of distant musketry…while preparing breakfast over the campfire, which Mrs. N. and I used in common, we were startled by cannonballs howling over our heads. Knowing my husband must go, I kept my place before the fire, that he might have his breakfast before leaving; but there was no time for eating, and though shells were flying faster, and musketry coming nearer, compelling me involuntarily to dodge as the missiles shrieked through the air, I still fried my cakes, and rolling them in napkins, placed them in his haversack, and gave it to him just as he was mounting his horse to assist in forming the regiment.

Belle and Mrs. N. began to run. Before they had gone far, they came upon ambulances filled with the wounded. They were being carried out and laid on the ground. “We stopped, took off our bonnets, and prepared to assist in dressing their wounds,” Belle wrote.

But an orderly dashed up, shouting orders to move the wounded immediately to the river. The rebels were closing in. Making their way to the river, Belle and her friend boarded the Emerald, one of the steamers that served as the headquarters of one of the Union officers. Soon the wounded came pouring in, and the women were busy for the next thirty-six hours caring for the injured soldiers.

“I dared not ask the boys if my husband was unharmed,” Belle wrote, “and feared each moment to see him among the almost lifeless forms that were being brought on board the boat.” All day long they heard the thunder of artillery, and spent bullets rained down on the deck of the boat.

Near sunset, the retreating Union soldiers were backed up to the riverbank. Just as it seemed they would be completely overrun, the gunboats Lexington and Tyler steamed upriver began to fire upon the Confederates. Union reinforcements could be seen on the opposite shore. As the transports ferried the soldiers across the river, the Federal officers tried to rally their commands.

At the Landing it was a scene of terror. Rations, forage, and ammunition were trampled into the mud by an excited infuriated crowd…. Trains (of supply wagons) were huddled together on the brow of the hill and in sheltered places. Ambulances were conveying their bleeding loads to the different boats, and joined to form a Babel of confusion indescribable.

By evening, the Emerald alone had 350 wounded on board. Nightfall brought a temporary halt to the fighting, while both sides tried to rest. But throughout the night, the gunboats fired their cannons on the Rebel positions.

There came a violent thunderstorm raged in the early morning, but with the dawn, “the sun came forth upon a scene of blood and carnage such as our fair land had never known.” The roads were muddy, but Belle and two friends set out to help at the hospital at the Union encampment. “We climbed the steep hill opposite the landing, picked our way past the long lines of trenches which were to receive the dead, and came to an old cabin, where the wounded were being brought,” Belle noted in her diary.

Inside, they found one room full of wounded, another with surgeons performing amputations. Belle pitched in to help. “The sight of a woman seemed to cheer the poor fellows, for many a ‘God bless you!’ greeted me before I had done them a single act of kindness.” Belle organized a bucket brigade to fetch water from the river. She bathed and bandaged their wounds, and distributed a small supply of bread.

By 3:00 p.m., Belle was totally exhausted. One of the surgeons gave her a spoonful of brandy, and she turned to go back to the boat. Just then she felt a hand on her shoulder and turned to see her husband.

I hardly knew him – blackened with powder, begrimed with dust, his clothes in disorder, and his face pale. We thought it must have been years since we parted. It was no time for many words; he told me I must go. There was a silent pressure of hands. I passed on to the boat.

After a nearly sleepless week of caring for the wounded, Belle was ordered to return to Peoria. She said goodbye to her husband:

Each parting seemed harder than the last for I knew now the dangers and uncertainties to which he was exposed. But my health had been failing… and I felt I must recruit now, or I might not be able to spend the summer with him.

She took the steamer Black Hawk for her trip back to Illinois. Several distinguished officials were her traveling companions, including the Governor of Illinois, Richard Yates. Belle was encouraged to recount her experiences at the bloody Battle of Shiloh.

One passenger was deeply moved by her story, and said that Belle deserved a commission for her meritorious service. Governor Yates agreed. When he learned that Belle’s husband was a lieutenant, he said that he believed in giving the women the best of it, and made Belle a major.

This event attracted the national media. Belle was featured in the May 17, 1862 issue of the national magazine, Harper’s Weekly. Some newspapers apparently had some difficulty with her military rank and called her “Mrs. Major Belle Reynolds.” When Belle returned to Peoria, she became a local celebrity.

After a brief period of rest, Belle rejoined her husband in the field and shared the hardships of camp life, seeing service in Mississippi, and witnessing the duel between Confederate shore batteries and Union gunboats at Vicksburg in July, 1863.

When Lt. Reynolds completed his term of service in the spring of 1864, the couple gratefully returned home.