Wife of Confederate General Sterling Price

During the Civil War, Martha Head Price left Missouri and settled in Washington, Texas. In the spring of 1866, she joined her husband in Mexico, and returned with him to Missouri the following year.

During the Civil War, Martha Head Price left Missouri and settled in Washington, Texas. In the spring of 1866, she joined her husband in Mexico, and returned with him to Missouri the following year.

Early Years

Born May 2, 1810 in Orange County, Virginia, Martha Head was the daughter of Judge Walter Head, a wealthy planter who emigrated to Missouri in 1830 from Orange County, Virginia.

Sterling Price was born on September 11, 1809, in Prince Edward County, Virginia, into a wealthy planting family. He received his education at Hampden-Sidney College. At the age of 22 went to Missouri with his father in 1831, first settling in Fayette, where Sterling worked in the tobacco commission business. A handsome and personable young man, he mixed easily in local society and politics.

Marriage and Family

Sterling Price married Martha Head in Randolph County, Missouri, on May 14, 1833. They lived on the farm south of Keytesville and had five children who survived to adulthood: Edwin Williamson (1834), Celsus (1841), Herber (1844), Martha Sterling (1846), and Quintus (1851).

Price was active in a number of enterprises. He operated an inn at Salisbury for a time, and in 1833 he ran a store in Keytesville for two years, investing his profits in land around his father’s extensive acreage. He then settled on a large farm eight miles south of that town, where he raised tobacco.

Price in Politics

In 1840, at the age of thirty-one, his fellow citizens elected Sterling Price to the Missouri legislature, where he was chosen Speaker of the House. In 1842 they re-elected him to both positions. He served six years in the legislature, four as the speaker.

By this time, Price was an established political leader, planter and entrepreneur. He was a good businessman and farmer and began developing a southern style manor named Val Verde, one of the finest tobacco plantations in the state. In 1843, he built a tobacco warehouse at Keytesville Landing to expand his business. In 1844, he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives.

When the Mexican War began he resigned, and was commissioned by President James K. Polk to raise and command a regiment of Missourians. Price served as the commander of the American forces in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

During an invasion into Mexico, Price captured the city of Chihuahua. His ability to handle troops was appreciated by the men on the field of action, as well as the authorities in Washington. By the end of the Mexican War he had reached the rank of Brigadier General. Martha Head Price managed their 400-acre farm in Chariton County and raised four young children while Price was in Mexico. By October 1848, he was back home, enjoying the praise of supporters.

The citizens of Missouri elected Sterling Price as their governor in 1852. Martha was suffering from an illness during his campaign for governor, but she attended the inaugural ceremonies at Jefferson City. During his administration, Price avoided getting involved in the border war with Kansas over the issue of slavery. Martha gave birth to their seventh child in the governor’s mansion a month before his term ended.

In January 1857, he gave up his governorship and gladly returned to his tobacco business. As president of Chariton and Randolph County Railroad Company, he raised money to build the railroad. In the meantime, his personal finances was in shambles, and the economic depression that followed the Panic of 1857 nearly ruined him. However, he neglected his own financial affairs, and he was Friends helped him win an appointment as state bank commissioner, and the salary eased his financial difficulties.

In 1860 Price supported the Union and Stephen A. Douglas for President. Though he owned several dozen slaves, Price opposed secession. Conditional Unionists like Price hoped for a compromise to prevent war. When southern states began seceding from the Union, a state convention was called in January 1861 to determine Missouri’s position. Price was elected president. The delegates voted to stay in the Union.

Price in the Civil War

On May 10, 1861, Federal Home Guard troops arrested pro-Southern militiamen and marched them through the streets of St. Louis, provoking a riot of civilians protesting the arrest. Guardsmen fired into a crowd, killing at least 28 unarmed civilians. Secessionists in the state government distrusted Price’s moderate stance, but they recognized his tremendous popularity. Somewhat reluctantly, the governor appointed Price major general in command of the State Guard.

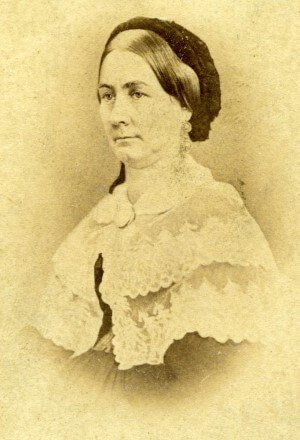

Image: Confederate General Sterling Price

Image: Confederate General Sterling Price

The State Guard engaged Federal troops throughout Missouri. At the Battle of Wilson’s Creek August 10, 1861, Price’s State Guard and Confederate forces met the Union army and pushed back its advance into southwestern Missouri. However, officials thought Price put the priorities of his own state above that of the Confederacy.

On September 11, 1861, Price led 7,000 men to Lexington, Missouri. Southerners joined his forces, and within a week his army had grown to nearly 10,000. On September 20 Price and his army captured the Union garrison in Lexington, which consisted of 3,500 prisoners, five pieces of artillery, 3,000 stands of arms, 750 horses, and about $100,000 worth of commissary stores. He also obtained the restoration of $900,000 which had been taken from the bank.

Price’s activities were publicized throughout the South, and he gained considerable popular acclaim. On October 20, 1861, the governor convened the state legislature at Neosho where it quickly passed an ordinance of secession, and Missouri was admitted as the 12th state in the Confederacy.

In February 1862 Price was forced from Missouri into Arkansas by overwhelming federal numbers and the lack of Confederate support. Price once again joined forces with McCulloch at the Battle of Pea Ridge (March 6–8, 1862), which resulted in a Union victory. That loss ensured Missouri would remain in Union control, a bitter disappointment for Price.

As in his previous battles, Price’s reckless courage in battle and his concern for his men intensified the soldiers’ admiration for the fatherly leader they affectionately called ‘Old Pap.’ In March 1862, Price finally accepted a commission as a Major General in the Confederate Army.

Price’s son Confederate Brigadier General Edwin Price grew tired of the rebellion in 1862, and he was later pardoned by President Abraham Lincoln providing he remain quietly at home.

Confederate President Jefferson Davis concentrated all western units on the east side of the Mississippi River, virtually abandoning the Trans-Mississippi states. Price’s troops were ordered to Memphis, Tennessee, but he promised his men that they would soon return, pledging that their government would not ask them to sacrifice their lives far from home while their beloved state fell prey to an army of occupation.

General Price led Missouri troops in combat at the battles at Iuka (September 19, 1862) and Corinth, Mississippi (October 3–4, 1862), after which Price wept openly for the hundreds of ‘his boys’ who lay dead or dying on the Mississippi battlefield. Price traveled to the Confederate capital of Richmond in early 1863, and requested of Confederate President Jefferson Davis that he and his Missouri troops be transferred back west of the Mississippi.

Instead, President Davis ordered him to return to the west without his men and raise another army in Arkansas and Missouri. Federal officials also recognized his leadership qualities and offered him a full pardon if he took an oath of loyalty to the Union, but Price went to work recruiting men and improving the living conditions of those already in service.

General Price led part of the Confederate attack on Helena, Arkansas on July 4, 1863, which was repulsed with heavy losses due to the difficulty of the terrain and a misinterpretation of orders. After the battle, Confederate officials gave the command of the entire army to Price, and they returned to Little Rock, Arkansas to prepare for a Union attack. During that engagement, Price was forced to abandon the capital city, and the Confederates retreated again.

On March 16, 1864, Price was also given command of the Confederate District of Arkansas, and he defended the Arkansas Confederate capital at Washington, Arkansas later that month. Stripped of all available infantry support, Price defended Washington, but the Federal army moved into the city of Camden.

Price’s Raid

Price received permission to lead a raid into Missouri to gather men and supplies and disrupt Federal communications. Even if he had to retreat the expedition would be successful if he brought a sizeable number of recruits into the army. If driven out of the state, Price was ordered to seize all the military supplies available.

On September 19, 1864, the general entered Missouri with 12,000 men, mostly raw recruits. Price realized early on that he lacked the manpower to seize St. Louis, and so he turned toward Jefferson City. Along the way, the invaders captured large quantities of Union weapons and uniforms, all of which were distributed to the ragged Confederate troops.

Moving across the state, Price’s army was attacked at Westport, Missouri (October 23, 1864), where the largest battle in the Trans-Mississippi Theater – engaging 45,000 men – ended with a Confederate defeat. Crossing into Kansas on October 24, Price was again defeated at Mine Creek (October 25). Two Confederate generals were captured along with eight colonels, 1,000 men and ten guns.

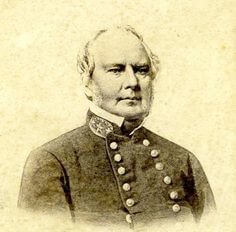

Image: Lincoln’s Pardon for Sterling Price

Image: Lincoln’s Pardon for Sterling Price

General Price made an arduous detour through Indian Territory to avoid Fort Smith. On December 2, 1864, he re-entered the Confederate lines at Laynesport, Arkansas, with 6,000 survivors of the ordeal. In summing up his operation Price said, “I marched 1,434 miles; fought forty-three battles and skirmishes; captured and paroled over 3,000 Federal officers and men; and captured 18 pieces of artillery.” He failed to mention that he had lost half of his army.

Fallout from Price’s Raid was severe. Any Confederate hopes of reclaiming the state of Missouri were dashed. Price was criticized for his actions by both Unionists and Confederates. Price’s expedition turned out to be the final significant Southern operation west of the Mississippi River. A court of inquiry was held in late April 1865, but the war ended and it was never concluded.

Price in Mexico

In early June 1865, Price and other Confederates set out for Mexico rather than surrender to the Union. On July 4, 1865, they joined General Joseph Shelby, who led his Iron Brigade across the Rio Grande at Eagle Pass, Texas. With him were several ex-governors and officers of the former Trans-Mississippi Department and their families who hoped to rebuild their lives there.

Sterling Price wrote to an unknown recipient, September 7, 1865:

I have chosen not to write you for prudential reasons, but now that the unfortunate storm has blown over so far as I am concerned, and I have arrived safe in this great city, and there are no further reasons why I should not do so, I again resume my correspondence with you, with great pleasure to myself. I am here with Governor [Trusten] Polk, Governor [Isham] Harris of Tennessee, Governor [Henry] Allen of Louisiana, Judge [John] Perkins of the Same State.

Price led an effort to establish the largest Confederate colony in Mexico at Carlota in the state of Vera Cruz, but guerrilla attacks, crop failure and illness ruined the settlement. He returned to St. Louis in January 1867 a broken and impoverished man. His old enemy Frank Blair offered him a presidential pardon. Price replied, “I have no pardon to ask.”

Price and his family settled in a house purchased by friends with the donations of thousands of Missourians, a token of their devotion to their former leader. In the spring he opened a commission business with his sons in St. Louis, but the old soldier’s health began to decline.

General Sterling Price died in St. Louis on September 29, 1867, and had one of the largest funerals in St. Louis history. He was buried in Bellefontaine Cemetery.

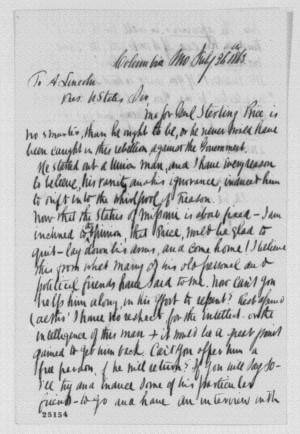

Image: Sterling Price Monument

Image: Sterling Price Monument

At Price Park in Keytesville, Missouri

To many Missourians, Price represented heroism, a reluctant secession forced by Northern aggression, and self-sacrificing patriotism through all the hardship of war. In 1911 his admirers petitioned the state legislature for $5,000, part of the governor’s salary that Price never collected. That sum with private donations was spent to erect a monument to the general’s memory in his hometown of Keytesville.

Martha Head Price died March 5, 1870 in St. Louis, Missouri.

SOURCES

Wiikipedia: Sterling Price

Encyclopedia of Arkansas History: Sterling Price

Impact of the Civil War in the Ozarks: Sterling Price

Missouri Civil War Sesquicentennial: Sterling Price