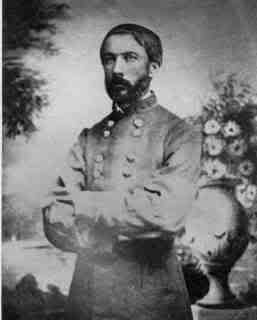

Wife of General ‘Stonewall’ Jackson

Anna met her future husband while visiting her sister, Isabella Morrison Hill, wife of future Confederate General Dana Harvey Hill, in Lexington, Virginia, where Jackson was a professor at the Virginia Military Institute.

Anna met her future husband while visiting her sister, Isabella Morrison Hill, wife of future Confederate General Dana Harvey Hill, in Lexington, Virginia, where Jackson was a professor at the Virginia Military Institute.

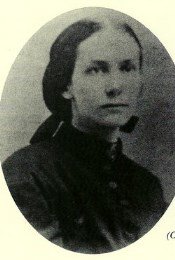

Image: Anna with daughter Julia Laura Jackson

Mary Anna Morrison – called Anna by friends and family – was born on July 21, 1831, in Charlotte, North Carolina, at Cottage Home, the plantation home of Reverend Robert Hall Morrison and Mary Graham Morrison. Her father was the first President of Davidson College in Charlotte. Anna grew up very differently than her famous husband.

Her parents had a large family, ten children who survived to adulthood. Life on the plantation was carefree for young Anna. Her parents were able to give her much affection and a good education. She was educated at Salem Academy from 1847 to 1849.

Born Thomas Jonathan Jackson on January 21, 1824, he often signed his name T.J. Jackson. His boyhood home, Jackson’s Mill, is located in present-day Weston, West Virginia. Orphaned early in life, Jackson was devoted to his younger sister Laura Jackson Arnold. He entered West Point in July 1842 with little previous education, but worked diligently and graduated in 1846, 17th in a class of 60.

Mary Anna Morrison met Thomas Jonathan Jackson in Lexington, Virginia, while she was visiting her sister, Isabella Morrison Hill, wife of future Confederate General Dana Harvey Hill, who was on the faculty of Washington College, also in Lexington. Jackson lived in Lexington from 1851-1861, while he was a professor of natural philosophy and artillery tactics at the Virginia Military Institute. He was a stern instructor and a quiet, profoundly religious man, and a frequent visitor at the Hill home.

At the time Jackson was engaged to Elinor Junkin, and they were married in 1853. Elinor died during childbirth in the fall of 1854 just after their first anniversary. The baby was a boy, but he was stillborn. Two years later, Jackson was still grieving and went on an extended tour of Europe. When he returned, he proposed to Anna Morrison. She was quite surprised at first, for Thomas had been very quiet and stern, but she now found him sweet and loving once in his closest circle. Jackson was eager to start a new family.

After a short courtship, Anna Morrison married Thomas Jonathan Jackson on July 16, 1857, at Cottage Home, the North Carolina home of the Morrison family. She was 25 years old; he was 33. Her family liked Thomas very much. On April 30, 1858, Thomas and Anna were blessed with a baby girl they named Mary Graham, but the infant died a few weeks later.

It seemed incomprehensible that another childbirth catastrophe could occur in his lifetime. First, Jackson’s mother passed away giving birth to his stepbrother. Then his first love and unborn son failed to survive delivery. Now his newborn daughter had been taken just a few weeks into her precious life. For most broken-hearted parents, the loss of a child is unbearable.

Jackson and Anna immediately turned to the healing power of prayer. Both were Sunday school teachers and were committed to daily study of the Bible. This routine would be repeated every day for the rest of their lives, whether they were together or apart. In 1859, Jackson and Anna bought a home in Lexington, the only home he ever owned. Anna wrote, “It was genuine happiness to him to have a home of his own… and it was truly his castle.”

They began decorating their home with furniture they bought on their honeymoon and other trips north. During the summer months, they worked in their flower and vegetable gardens, but they were to enjoy their peaceful lifestyle for only a few years.

Jackson’s routine at home was rigid. Family prayers were held at 7 o’clock in the morning, summer and winter, and all members of his household were required to be present, but the absence of anyone did not delay the services a minute. Breakfast followed, and he went to his classroom at 8 o’clock, remaining until 11, when he returned to his study.

Between dinner and supper his attention was occupied by his garden, his farm, and the duties of the church, in which he was a deacon. After supper he devoted his time for half an hour to a mental review of the studies of the next day, without reference to notes, then to reading or conversation until 10 o’clock, at which time he always retired. There was no variation in this daily program.

Jackson in the Civil War

The Jacksons’ brief period of domestic tranquility ended on April 21, 1861, when Virginia seceded from the Union. Believing that his first and highest loyalty was to his native state, Jackson promptly offered his services to Virginia when war was declared against it. He and other VMI officers were ordered to Richmond to begin the conflict he would later describe as “the sum of all evils.”

Major Jackson left home to lead the Virginia Military Institute cadets to Richmond, where he was commissioned a brigadier general in the Confederate Army. No one imagined what a great military leader he would turn out to be. For a time, Anna remained at their home in Lexington, but soon began to travel back and forth between her parents’ plantation, Cottage Home, and friends and relatives in the Richmond area.

From 1861-63, the Jacksons were apart more than they were together. During the time apart, the couple kept the lines of communication flowing with frequent letters. Jackson was a brigade commander during the First Battle of Bull Run. During that battle, he moved his troops in to reinforce the Confederate left to stop the Union’s advancing attack.

To rally his men, General Bernard Bee pointed to Jackson’s unit and shouted to his fleeing troops, “There stands Jackson like a stone wall, rally behind the Virginians!” After that day, Thomas was known as Stonewall Jackson, and his brigade as the Stonewall Brigade. He was a skillful soldier and a fine leader, loved and respected by his men, whom he often led in prayer. He disliked fighting on Sunday, though that did not stop him from doing so.

In the winter of 1861-62, Lt. Colonel Lewis Tilghman Moore, commander of the 31st Virginia Militia, offered his home in Winchester to serve as the headquarters for Jackson, while his troops were in winter quarters. Jackson lived there from November 1861 to March 1862.

Anna joined Jackson in Winchester in December 1861. As he routinely moved through his army, leaving nothing unchecked, he had ample opportunity to spend time with his beloved Anna. While living there, the Jacksons became very fond of the people and culture of Winchester, and referred to it as their winter home.

Image: Until We Meet Again Mort Kunstler, Artist

Image: Until We Meet Again Mort Kunstler, Artist

The Lewis T. Moore house in Winchester, Virginia, served as Jackson’s headquarters in the winter of 1861-62. But when Anna joined him they stayed at the home of Dr. Graham (the house in the background), a few doors away from headquarters. This scene shows the general saying goodbye to Anna.

Jackson quickly became famous for his leadership of Confederate forces, especially during the Valley Campaign in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia in the spring of 1862, which included six major battles: Kernstown (March 23), McDowell (May 8), Front Royal (May 23), Winchester (May 25), Cross Keys (June 8) and Port Republic (June 9).

Using complex maneuvers to isolate, confuse, and overwhelm the Union forces in the Valley, Jackson defeated the three armies that President Abraham Lincoln sent to secure the Shenandoah Valley for the Union. Relying on tactical deception, he became known and feared for his highly effective use of misdirection and elaborate maneuver.

Most Famous General in the Confederacy

This audacious campaign elevated Jackson to the position of the most famous general in the Confederacy and has since been studied by military organizations around the world. He rose rapidly in rank in the Confederate Army. By October 1862, he had been promoted to lieutenant general. A Confederate soldier wrote of Jackson:

From the calm, collected [person that he appears to be], he becomes the fiery leader. Passing like a thunderbolt along the front he is everywhere in the thickest of the fight, holding his lines steady, however galling the fire, and rallying his men to charge where the danger is greatest and the pressure heaviest…

Serving under General Robert E. Lee, Jackson and his troops were victorious at Second Bull Run (August 28–30, 1862) and Fredericksburg (December 11–15, 1862). Jackson and his men became famous for the speed at which they could march. Military historians call Jackson an outstanding strategist and one of the most gifted tactical commanders in United States history.

During the winter encampment of 1862-63 General Jackson became a father for the third time. The first two children died during childbirth or shortly thereafter, so he was delighted to receive a letter announcing the birth of Julia Laura Jackson, on November 23, 1862. The baby was named for Jackson’s mother and sister, and she was the only Jackson child to survive into adulthood.

Anna and the baby visited Jackson in April 1863. Anna had not seen her husband for thirteen months, and she later wrote that their time together was all the more joyful because of the baby. To provide a keepsake of the happy occasion, Anna persuaded her husband to sit for a photograph. But their nine-day reunion was interrupted by a renewal of the fighting. Anna and the baby returned to Cottage Home to live with Reverend Morrison.

Anna Jackson letter to General Jackson in late April 1863:

My precious husband, I will go to Hanover and wait there until I hear from you again, and I do trust I may be permitted to come back to you again in a few days. I am much disappointed at not seeing you again, but I commend you, my precious darling, to the merciful keeping of the God of battles, and do pray most earnestly for the success of our army this day. Oh! that our Heavenly Father may preserve and guide and bless you, is my most earnest prayer. I leave the shirt and socks for you with Mrs. Neale, fearing I may not see you again, but I do hope it may be my privilege to be with you in a few days. Our little darling will miss dearest Papa. She is so good and sweet this morning. God bless and keep you, my darling, Your devoted little wife

Tragedy at Chancellorsville

The Army of Northern Virginia was faced with a serious threat by the Army of the Potomac and its new commanding general, Major General Joseph Hooker. To take the initiative away from Hooker, General Lee decided to employ a risky tactic and divide his forces. On May 2, 1863, Jackson and his entire corps were sent on an aggressive flanking maneuver to the right of the Union lines, which would be one of the most successful and dramatic of the war.

While riding with his infantry in a wide berth well south and west of the Federal line of battle, Jackson employed General Rooney Lee’s cavalry to provide reconnaissance in regards to the exact location of the Union right and rear. The results were far better than Jackson could have hoped. Lee found the entire right side of the Federal lines in the middle of an open field, guarded merely by two guns facing westward.

Lee took Jackson to the top of a hill where he could see for himself. The Union soldiers were leisurely eating and playing games, completely unaware that an entire Confederate corps was less than a mile away. Jackson immediately returned to his corps and arranged his divisions into a line of battle to charge directly into the oblivious Federal right. The Confederates marched silently until they were merely several hundred feet from the Union position, then released a bloodthirsty cry and a full charge.

The attack shattered two miles of the Union line. Many of the Federals were captured without a shot fired, the rest were driven into a full rout. Jackson pursued relentlessly back toward the center of the Federal line until dusk. That evening Jackson and his staff rode forward with some of his men to check the position of his lines in preparation for a meeting with General Robert E. Lee to discuss plans for renewing the battle the following morning.

As they were riding back through the woods on horseback, they were mistaken for Union cavalry. Confederate soldiers opened fire, and Jackson was hit by three bullets, one in the right hand and two entered the general’s left upper arm, fracturing his humerus. It wasn’t necessarily a fatal wound, but a large artery was damaged, and it bled profusely. Darkness and confusion prevented Jackson from getting immediate medical care. He was dropped from the stretcher while being evacuated because of incoming artillery rounds.

At the field hospital near Wilderness Tavern the medical director of Jackson’s Corps, Dr. Hunter McGuire, removed a ball from the General’s right hand and amputated his left arm. The general seemed to be doing fine the following morning, and was in good spirits. He sent his brother-in-law to Richmond to tell Anna about his wounding and to bring her back with him.

In the afternoon, General Lee sent a message to move Jackson to Guinea Station where he could recuperate in a safe place well behind friendly lines. Lee selected Guinea Station as the best location for Jackson because of its proximity to the railroad to Richmond. Lee also sent a personal message: “Give him my affectionate regards, and tell him to make haste and get well, and come back to me as soon as he can. He has lost his left arm, but I have lost my right arm.”

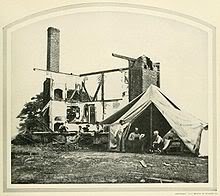

On May 4, 1863, the general left the field hospital in an ambulance. Jedediah Hotchkiss, Jackson’s topographical engineer, had helped ease his commander’s trip by preceding the ambulance with a crew of men who removed obstructions from 27 miles of rough country roads. Jackson felt well and was talkative during the trip. They arrived at Thomas and Mary Chandler’s 740 acre plantation named Fairfield near Guinea Station about 8:00 pm. He was offered Chandler home, but Jackson chose the plantation office building instead.

If all went well, the general would soon board a train to Richmond and the medical expertise available there. Jackson hoped that after a few days of rest he could go home to Lexington. The following morning, the general was alert when he awakened. His wounds were doing well, and he ate heartily and was cheerful throughout the day. Five different physicians examined Jackson, but Dr. McGuire was the only physician present the entire six days.

The general was thought to be out of harm’s way, but complained of a sore chest, which was thought to be the result of his rough handling in the battlefield evacuation. On May 7, he woke up about 1:00 am, complaining of nausea and pain in his right side, which Dr. McGuire diagnosed as pneumonia. Pneumonia so soon after amputation was not a good sign. His doctors treated his pain with mercury, antimony and opium.

Anna and the baby arrived later that day. Just eight days earlier she had left him in robust health. Jackson had to be aroused to speak to her and soon nodded off again, but in the afternoon, he seemed better, and the doctors had hope of his recovery. But Anna later said that he lay most of the time in a semiconscious state.

On May 8, the pain in his right side had eased, but he was breathing with great difficulty and complained of exhaustion. His fever and restlessness increased. Despite the efforts of pneumonia specialists, nothing seemed to bring relief to the General. He observed, “I see from the number of physicians that you think my condition dangerous, but I thank God, if it is His will, that I am ready to go.”

On May 10, the general was unconscious all morning. Later, he brightened a bit. Anna brought five-month-old Julia into the room and placed her on the bed. The general’s face lit up with a smile, and said, “Little darling sweet one,” then fell back into unconsciousness. The doctors lost all hope of Jackson’s recovery. Anna later wrote, “Tears were shed over that dying bed by strong men who were unused to weep.” Dr. McGuire carefully noted Jackson’s last words:

A few moments before he died he cried out in his delirium, ‘Order A.P. Hill to prepare for action! Pass the infantry to the front rapidly! Tell Major Hawks’ – then stopped, leaving the sentence unfinished. Presently a smile of ineffable sweetness spread itself over his pale face, and he said quietly, and with an expression, as if of relief, ‘Let us cross over the river, and rest under the shade of the trees.’

Lt. General T.J. Stonewall Jackson died of complications from pneumonia on May 10, 1863, at 3:15 in the afternoon. The great tactical commander and Southern gentleman was gone at the age of 39. His body was moved to the Governor’s Mansion in Richmond for the public to mourn his passing, before being brought back to Lexington for burial in a plot that he had bought for his family.

Upon hearing of Jackson’s death, General Lee told his cook, “William, I’m bleeding at the heart.” Jackson’s death was a severe setback for the Confederacy, affecting not only its military prospects but the whole morale of the army. It is doubtful that the Army of Northern Virginia ever fully recovered from the loss of Jackson’s leadership in battle.

After the funeral on May 15, Anna returned with baby Julia to her father’s house in North Carolina. She wore mourning clothes for the rest of her life and never remarried. She was involved in the reunions of Confederate veterans throughout the South in the years following the war, and became known as the ‘Widow of the Confederacy.’

Anna and Julia moved to Charlotte in 1873 so that Julia could attend the Charlotte Institute for Young Ladies. In 1885, Julia Laura Jackson married William Christian and they had two children: Julia Jackson Christian and Thomas Jonathan Jackson Christian. Julia Jackson Christian died of typhoid fever in 1889, at age 26, and Anna raised her two grandchildren.

Anna Jackson wrote two books about her husband: Life and Letters of General Thomas J. Jackson, published in 1892, and the story of his remarkable service during the Civil War, which was published as Memoirs of Stonewall Jackson in 1895. In the Preface of Memoirs, Anna wrote:

For many years after the death of my husband the shadow over my life was so deep, and all that concerned him was so sacred, that I could not consent to lift the veil to the public gaze. But time softens, if it does not heal, the bitterest sorrow; and the pleadings of his only child, after reaching womanhood, finally prevailed upon me to write out for her and her children my memories of the father she had never known on earth. She was my inspiration, encouraging me, and delighting in every page that was written; but the work was not more than half completed when God took her to be with him whose memory she cherished with a reverence and devotion which became more intense with the development of her own pure and noble character. After her departure, which was truly sorrow’s crown of sorrows, I had no heart to continue the work; but, remembering how earnestly she wished me to write it for her and her children, I renewed the effort to finish it, for the sake of the precious little ones she left. In forcing my mind and pen to do their task, I found some surcease of sorrow in carrying out her wishes; and, as I went on, the grand lessons of submission and fortitude of my husband’s life gave me strength and courage to persevere to the end.

In 1898 Anna organized the Stonewall Jackson Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy in Charlotte, and was elected President for life. She presided over the activities of the chapter until failing health forced her to give up her duties. In her last years, Anna lived in Charlotte with her granddaughter, and remained a beloved figure in the South.

Her Christian faith, great wisdom and courageous disposition marked her as a most unusual woman, whose plan of life was as simple as her husband’s: finding out each day what she believed to be her duty, and then doing it uncomplainingly and with as little affectation as possible.

In 1907, when offered a pension by the Legislature of North Carolina, though she greatly needed it, she authorized one of her relatives, then a member of that body, to say that she preferred the money be given to help needy soldiers, or to found a school for wayward boys. At this session the Stonewall Jackson Training School was chartered.

Mary Anna Morrison Jackson died on March 24, 1915, in Charlotte, North Carolina, at the age of 83.

On July 20, 1997, the Virginia Division of the United Daughters of the Confederacy gathered at the Stonewall Jackson Cemetery at Lexington, Virginia, to lay a UDC grave marker at the final resting place of one of their own, Mary Anna Morrison Jackson

SOURCES

Heroines of History

Wikipedia: Stonewall Jackson

Thomas Jonathan Stonewall Jackson