Wife of Union General Darius Nash Couch

Mary Caroline Crocker was born on March 18, 1829, at Taunton, Massachusetts. She was a direct descendant of the distinguished Crocker and Leonard families of Taunton. Darius Nash Couch was born on July 23, 1822, on a farm in the village of South East in Putnam County, New York. Couch, who pronounced his name Coach, was educated at the local schools there.

Mary Caroline Crocker was born on March 18, 1829, at Taunton, Massachusetts. She was a direct descendant of the distinguished Crocker and Leonard families of Taunton. Darius Nash Couch was born on July 23, 1822, on a farm in the village of South East in Putnam County, New York. Couch, who pronounced his name Coach, was educated at the local schools there.

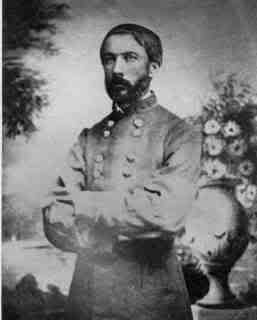

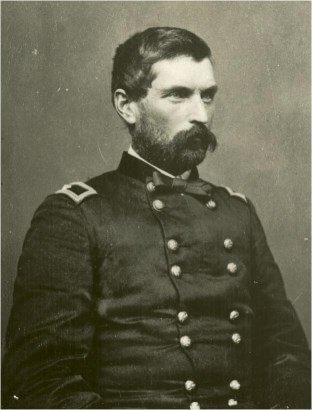

Image: General Darius Couch

Civil War Photographic Collection, Library of Congress

In 1842, Couch entered the United States Military Academy at West Point, less than 50 miles west of his family’s home, graduating in 1846, 13th out of 59 cadets. Couch’s illustrious classmates included several future Civil War generals: Thomas (Stonewall) Jackson, George Brinton McClellan, Ambrose Powell Hill, George Edward Pickett, Cadmus Marcellus Wilcox, and George Stoneman.

On July 1, 1846, Couch was commissioned a second lieutenant and assigned to the 4th U.S. Artillery. Couch then saw action with the U.S. Army during the Mexican-American War, most notably in the Battle of Buene Vista on February 22, 1847. For his actions on the second day of this fight, he was brevetted a first lieutenant for “gallant and meritorious conduct.” He was described as courageous, very thin in build, and after Mexico of frail health.

After the Mexican war ended in 1848, Couch began serving garrison duty at Fort Monroe in Hampton, Virginia. The following year he was stationed at Fort Pickens near Pensacola, Florida, and then in Key West. He participated in the Seminole Wars during 1849 and into 1850.

Returning to garrison duty later that year Couch was sent to Fort Columbus in New York Harbor, and in 1851, was involved in recruiting at Jefferson Barracks on the Mississippi River. Later in 1851 he returned to Fort Columbus, and then was ordered to Fort Johnston in Southport, North Carolina, staying there into 1852, and next in garrison at Fort Mifflin in Philadelphia until 1853.

After that, Couch took a one-year leave of absence from the army from 1853 to 1854 to conduct a scientific mission in northern Mexico to collect plant, mineral and animal specimens for the Smithsonian Institute. There, he discovered the species that were known as Couch’s Kingbird and Couch’s Spadefoot Toad, which is a species of North American spadefoot toad native to the southwestern United States and the Baja region of Mexico.

Mary Caroline Crocker married Darius Couch on August 31, 1854, in Taunton, Massachusetts.

From 1855 to 1857, Couch was a merchant in New York City. He then moved to Taunton, and worked as a copper fabricator in the company owned by his wife’s family. Couch was still working in Taunton when the Civil War began in 1861, when he enlisted again.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Couch was appointed commander of the 7th Massachusetts Infantry with the rank of colonel in the Union Army on June 15, 1861. In August, he was promoted to brigadier general, and was given a brigade to command in the Army of the Potomac that fall, and command of a division in the VI Corps the following spring.

Couch participated from March through July 1862 in the Peninsula Campaign, fighting in the Siege of Yorktown and the Battle of Williamsburg. He led his division during the Battle of Seven Pines on May 31 and June 1, 1862. In this engagement, corps commander General Erasmus Keyes ordered Couch’s division forward of the Union defensive line. This placed him in an isolated position, vulnerable to attack on three sides; however poorly coordinated Confederate movements allowed Couch to prepare entrenchments for the impending assault. Couch continued to lead his division during the 1862 Seven Days’ Battles that followed, fighting at Oak Grove on June 25 and Malvern Hill on July 1.

Later in July, Couch’s health began to fail, prompting him to offer his resignation. The army commander, Major General George B. McClellan, refused to send it to the U.S. War Department, and instead Couch was promoted to major general, to date from July 4, 1862. Couch was involved in the Maryland Campaign that fall, although absent from the Antietam on September 17.

On November 14, 1862, Couch was assigned command of the II Corps, which he led during the Battle of Fredericksburg. His corps contained three divisions, led by Brigadier Generals Winfield Scott Hancock, Oliver O. Howard, and William H. French.

Early on December 12, infantry from Couch’s corps attempted to support the Union engineers’ efforts to lay a pontoon bridge across the Rappahannock River to allow the Union soldiers to cross into the town of Fredericksburg. When Confederate fire prevented this, the decision was made to send small groups of soldiers in pontoon boats across to dislodge the enemy. This amphibious assault was executed by one of Couch’s brigades, which finally succeeded in driving out the Confederates.

The next day, Couch’s corps was ordered to attack the strongly Confederate position on a hill above Fredericksburg called Marye’s Heights. Couch, along with many of the generals under General Ambrose Burnside, vehemently opposed the planned attack.

When the time came, Couch gave the order for his men to advance, then returned to Union headquarters (the Philips House) on an overlook north of Fredericksburg to watch the disaster. Even as Hancock, Howard, and French began lining up their men, Rebel artillery and sharpshooters were devastating the line. As they approached the Confederate defenses, Couch could see his men being easily repulsed, describing it “as if the division had simply vanished.”

Hancock’s division followed, meeting the same fate with high casualties as well. Howard, who was to go in next, was with Couch as Hancock’s division attacked. Briefly through the smoke they could see the mounting casualties, and Couch reportedly said “Oh, great God! See how our men, our poor fellows, are falling.”

Couch ordered Howard to march his division toward the right and possibly flank the Union defenses his other two divisions had failed to dislodge. However, the terrain did not permit any force marching towards Marye’s Heights to attack anywhere other than at the stone wall along its base. At one point, Couch asked Burnside to call off the attack; Burnside refused. Couch then returned to his corps and tried to rally his men.

When Howard’s men attacked, they were crowded back to the left, meeting the same resistance, and were repulsed. As other Union soldiers followed the II Corps in, Couch ordered his artillery to move into the field and blast the Confederates at close range. When his own artillery chief protested exposing the gun crews in this fashion, Couch stated that he agreed, but it was necessary to slow the Confederate fire in some way.

The cannon stopped about 150 yards from the stone wall and opened fire, but quickly lost most of their crews and did little to slacken the enemy fire. During this Couch moved slowly along his line of men, who remained on the ground firing as best they could until nightfall. The II Corps suffered tremendously – losing close to 4000 enlisted men and officers.

That night, the Union wounded remained in the field, and Couch wrote after the war what he saw: “It was a night of dreadful suffering. Many died of wounds and exposure, and as fast as men died they stiffened in the wintry air, and on the front line were rolled forward for protection to the living. Frozen men were placed for dumb sentries.”

Darius Couch Monument

Darius Couch Monument

Dedicated June 25, 2005

This monument to General Couch and the Union Troops was placed at Fort Couch in Lemoyne, PA, the only remaining breastworks of the once extensive fortifications protecting Harrisburg. The monument was designed by Camp Curtin’s Past President Robin Lighty and is reminiscent of the earthen mounds that formed the fortifications. It includes etchings of photographs, drawings and maps along with a biography of General Couch and descriptions of the fortifications.

Following the Union defeat at Fredericksburg and the inglorious Mud March in January 1863, General Burnside was relieved of command and replaced by Major General Joseph Hooker, who reorganized the army and drew up plans for a new campaign against Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. He wanted to avoid attacking the Confederate defenses at Fredericksburg and flank them out of position, thereby fighting on open ground.

After the army reorganization, Couch continued to lead the II Corps, with his divisions commanded by Hancock and French (both now major generals) and Brigadier General John Gibbon at the head of Howard’s former division, a total of about 17,000 soldiers.

During the ensuing Chancellorsville Campaign, Couch was senior corps commander, Hooker’s second-in-command. In late April, Hooker began moving his corps across the Rappahannock and Rapidan Rivers, ordering Couch to send two of his divisions to entrench and defend the Banks’ Ford crossing of the Rappahannock, and to detach Gibbon’s 5000 men to remain at the Union camp back at Falmouth on April 29.

The following day, Couch had cleared the ford and was marching toward Chancellorsville. In the afternoon of May 1, Hooker—normally quite aggressive—cautiously slowed his marching army, and soon stopped their movement altogether, despite some success against the Confederates and the loud protests of his corps commanders.

Couch sent Hancock’s division to bolster the Union men already engaged and informed Hooker they could handle the enemy in front of them. But Hooker ordered them to march back into the positions they held the previous day and assume a defensive posture. Couch complied and ordered Hancock’s division to form a rear guard as they withdrew.

As Hancock formed his men, Couch could see Confederate artillery aiming for the massed Union columns, and he told his staff, “Let us draw their fire.” The group of mounted officers clustered around a clearing where the enemy cannon could easily see them, thus attracting their fire and sparing the marching infantry; Couch and his staff also went unharmed. By nightfall, the Union soldiers were busy fortifying the ground. Couch formed his divisions behind the XII Corps in roughly the center of Hooker’s line.

By late afternoon on May 2, Hooker’s line was hit on the right by Confederates under Lt. General T.J. “Stonewall” Jackson, and despite resisting, the XI Corps was overwhelmed and retreated hastily toward Chancellorsville. The remaining corps tightened into a “U” shaped formation by May 3, and Confederate artillery began shelling their positions, including Couch’s men.

At about 9 a.m. that day, Hooker was stunned by enemy fire when a shell hit the pillar he was leaning on, temporarily incapacitating him and destroying his headquarters at the Chancellor house. At that time, Hooker turned command of the army over to Couch, and through consulting with a “groggy” Hooker, it was decided to withdraw the army to defensive lines to the north, with the other commanders strongly advocating an attack instead. Couch is rarely listed as the army commander since command was not assigned by the War Department and Abraham Lincoln.

On June 9, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln, responding to General Robert E. Lee‘s impending invasion of Maryland and Pennsylvania, called for 100,000 volunteers from Pennsylvania, New York, and Ohio to help repel the invasion, with only about 33,000 recruits answering his call. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton ordered the creation of two military departments, the Departments of the Susequehanna and Monongahela, to organize these militia and defend the state of Pennsylvania.

Major General Darius Couch was given command of the newly created Department of the Susquehanna during the Gettysburg Campaign in the summer of 1863. Its goal was to protect the state capital at Harrisburg and southern Pennsylvania, and to deny the Confederate Army passage across the vital Susquehanna River. The Department was initially headquartered at Chambersburg. As the Confederates entered the Cumberland Valley, Couch moved his headquarters to Harrisburg.

Assigned to protect Harrisburg from a threatened Confederate attack by CSA General Richard Ewell’s Corps, General Couch oversaw the building of a fort on the west side of the Susquehanna River on the heights overlooking the railroad and turnpike bridges crossing the capital city. Officials called for volunteers to dig earthworks. Late that afternoon, a large crowd of civilians began to dig. As darkness fell, men set piles of brush on fire to provide enough light to continue digging through the night.

The initial enthusiasm, however, soon gave way as blistered hands and weariness slowed the work. To complete the earthwork defenses, the Pennsylvania Railroad sent railroad construction gangs. Many of them were African Americans, who were joined by other blacks from the steady stream of refugees fleeing before the advancing Confederates.

On June 19, General Couch announced in general orders the completion of the fort, which he named Fort Washington, as part of the emergency response to the Confederate invasion of Pennsylvania. The fort consisted of entrenchments and earthen redoubts with wooden platforms for 25 pieces of artillery. It occupied about 60 acres and was manned by New York National Guard and Pennsylvania Militia under General Couch.

Couch realized that the fort could be dominated by enemy soldiers occupying higher ground half a mile to the west; he ordered construction of a second entrenchment on higher ground, as an advance position to ensure the defense of Fort Washington. Construction of Fort Couch started on June 20, 1863, by command of General Couch and on the advice of Army engineers. Surviving references indicate that the second fort was never completed.

Artillery pieces were mounted on wooden platforms behind the earthworks and pointed west. Fort Couch was manned by New York National Guard, Pennsylvania Militia, and Federal troops evacuated from the U.S. Army Barracks at Carlisle, PA, which included members of the 4th U.S. Cavalry Regiment. Several forward infantry picket lines were established between Fort Couch and Oyster Point located a mile and a half to the west.

CSA General Albert Jenkins’ Cavalry Brigade was in the Harrisburg area as the vanguard of General Ewell’s Corps, scouting the defenses of Harrisburg. New York troops of the Department of the Susquehanna first skirmished with the Confederate cavalry on June 20. The New Yorkers eventually retired to Harrisburg, allowing Jenkins to occupy Chambersburg.

General Couch ordered that no Confederate unit be allowed to cross the Susquehanna River. He assigned William “Baldy” Smith to defend Harrisburg, the state capital, and designated Major Granville Haller, as the sector commander to defend Adams and York counties, with regional headquarters in Gettysburg.

On June 26, 1863, advancing Confederates under CSA Generals Jubal Early and General John Brown Gordon routed Haller’s militia at Gettysburg and occupied the town. General Ewell arrived in Carlisle, PA, on June 27, and occupied the town the following day. Confederate scouts ranged widely, and Harrisburg newspapers reported the sighting of enemy horsemen.

York surrendered to General Early on June 28, becoming the largest Northern town to fall during the Civil War. Prior to the Confederate occupation, Haller had removed his troops to Wrightsville, which was bombarded by General Gordon the following day. In obedience to Couch’s orders, Major Haller burned the covered bridge across the Susquehanna, stopping the Rebel advance.

The troops Couch assigned to General Smith skirmished with Confederate cavalry under General Jenkins on June 29-30, 1863, at Oyster Point and Sporting Hill, the northernmost engagements of the Gettysburg Campaign. Therefore, Couch’s militia played a strategic role in delaying the advance of Confederate troops and preventing them from crossing the Susquehanna River.

Plans were being made for Ewell’s troops to move from Carlisle to Harrisburg to join Jenkins when General Robert E. Lee sent orders to consolidate the Confederate Army near Gettysburg. On June 30, General Ewell marched south, and did not attack Harrisburg. Couch then dispatched Smith’s men and many of Haller’s to help General George Meade pursue the retreating Army of Northern Virginia.

With the threat repelled, General Couch moved his headquarters back to Chambersburg, and the department played an administrative role during the rest of the year, providing militia to help cleanup the Gettysburg Battlefield and assisting in the military preparations for the dedication of the Gettysburg National Cemetery and President Abraham Lincoln‘s visit and his Gettysburg Address.

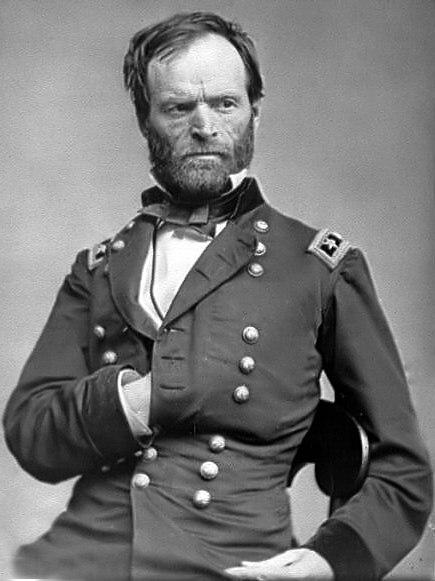

Image: Fort Couch

Image: Fort Couch

This fort was built as part of the emergency fortifications erected to defend Harrisburg and nearby bridges across the Susquehanna River during the summer 1863 invasion of Pennsylvania by Confederate forces.

After the Gettysburg Campaign, Forts Couch and Washington were abandoned. Today, only a portion of Fort Couch remains to remind local residents of Lee’s planned attack on the state capital in June of 1863.

The Department of the Susquehanna remained operational following the conclusion of the Gettysburg Campaign. In March 1864, there were rumors of yet another raid, and Couch made preparations to again defend the state. However, it was not until late July that the Confederates again arrived in Pennsylvania, when General John McCausland raided and burned Chambersburg, in retaliation for the destruction of private property by Union General David Hunter in the Shenandoah Valley, including the burning of the Virginia Military Institute.

In August 1864, the department again responded to a threatened Confederate border raid. USA General Philip Sheridan’s subsequent victories in the Valley Campaigns of 1864 finally removed any further threats. The Department of the Susquehanna remained in existence until December 1, 1864, when it was merged into the Department of Pennsylvania.

In December 1864, General Couch returned to the front lines with an assignment in the Western Theater, where he commanded a division in the XXIII Corps of the Army of the Ohio in the Franklin-Nashville Campaign in Tennessee and for the remainder of the war.

As the war ended, so did Couch’s military service. He returned to civilian life in Taunton after the war, where he tried his hand at politics, but ultimately failed. He later briefly served as president of a mining company in West Virginia.

Couch moved to Connecticut in 1871, where he served as the Quartermaster General of the state militia until 1884. He then moved to Norwalk, Connecticut, where he held the position of

Adjutant General of the state.

Darius Nash Couch died on February 12, 1897, in Norwalk, Connecticut. He was buried in Mount Pleasant Cemetery in Taunton, MA.

Mary Caroline Crocker Couch died on December 29, 1912, and was buried with her husband.

Carsten Norgaard portrayed General Darius Couch in the 2002 film, Gods and Generals.

SOURCES

Fort Couch

Darius Couch

Darius N. Couch

Darius Nash Couch

The Confederate Invasion

Department of the Susquehanna

Civil War Comes to York County