Wife of Union General Philippe Regis de Trobriand

Mary Mason Jones was born in 1819, the daughter of Isaac and Mary Jones. Her father was the president of the Chemical Bank, and her mother was American novelist Edith Wharton’s great-aunt, and the model for the high and mighty Mrs. Mingott in the Wharton’s novel, The Age of Innocence.

Mary Mason Jones was born in 1819, the daughter of Isaac and Mary Jones. Her father was the president of the Chemical Bank, and her mother was American novelist Edith Wharton’s great-aunt, and the model for the high and mighty Mrs. Mingott in the Wharton’s novel, The Age of Innocence.

Image: The Countess de Trobriand

Frederick MacMonnies, Artist

Oil on canvas, 1901

This portrait depicts the countess in regal splendor, sitting on a golden throne with an ermine wrap at her side. The egret feather in her hair shows that she has been presented at the court of Napoleon III. According to Jones family legend, MacMonnies painted this portrait in Paris, working only during the receptions in her drawing room on Sunday afternoons.

Philippe Regis de Keredern de Trobriand was born outside Tours, France, on June 4, 1816, at his father’s Loire chateau. Philippe was an aristocratic Frenchman, the son of a baron of ancient lineage who had been one of Napoleon’s generals.

De Trobriand’s early education was for a military career. He studied at the College Saint Louis in Paris, the College of Rouen, where his father was in command, graduated from the College de Tours, and went on to receive a degree in law from the Poitiers in 1837. In his youth, he studied law and wrote poetry and prose, publishing his first novel in 1840. He was an expert swordsman and fought a number of duels.

In 1841, the young and dashing de Trobriand came to the United States at the age of twenty-five, and mingled with the social elite of New York City, where he met and became engaged to heiress Mary Mason Jones. De Trobriand was welcomed for his charm and accomplishments as a novelist, poet, editor, and painter.

Mary Mason Jones married Philippe Regis de Trobriand in Paris in 1843. The couple traveled about Europe for a few years, eventually taking up residence in Venice, Italy. This grand court life came to an end when in 1847, at the request of Mary’s father, they returned to New York City and took up permanent residence there. Mary took her place in fashionable society, and de Trobriand made a living by writing for and editing French language publications, becoming one of the city’s literary group of the 1850s.

The couple had two children: Marie Caroline Denis de Keredern de Trobriand, born in 1845, and Charlotte Antoinette Béatrice Denis de Keredern de Trobriand, born in New York in 1850.

When the Civil War began in 1861, de Trobriand became an American citizen, and enlisted in the Union Army. In August 1861, he was commissioned a colonel and given command of the 55th New York regiment, called the Lafayette Guards – a predominantly French unit attached to the New York Militia.

De Trobriand and the 55th did their first fighting with the Army of the Potomac in early May 1862 in the Peninsula Campaign, at Williamsburg. He showed well there, but by mid-May was left prostrate in a shanty with “swamp fever.” Ill, he missed the rest of the campaign, not able to return until mid-July. After this campaign, the regiment was assigned to the III Corps (General Philip Kearny’s).

On December 13, 1862, de Trobriand participated in the Battle of Fredericksburg with three regiments under his command – the 55th New York, 99th Pennsylvania, the 3rd Maine, and later in the day, the 57th Pennsylvania. Soon after Fredericksburg, the 55th was merged with the 38th New York (Ward’s old command), and de Trobriand was placed in charge of the combined regiment.

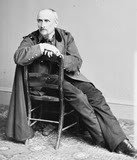

Image: General Philippe de Trobriand

Image: General Philippe de Trobriand

De Trobriand led the new 38th for the first time at Chancellorsville. Though he was not in heavy fighting, he was first on the list of commendations after the battle. When the III Corps was reorganized after its terrible losses at Chancellorsville, de Trobriand was given command of the newly formed Third Brigade, First Division, III Corps, but remained at the rank of colonel.

De Trobriand was a distinguished citizen soldier, but he had no battle experience leading a brigade, and even his regimental experience in combat was meager compared to many others. On July 1, the first day of the Battle of Gettysburg, de Trobriand’s brigade was one of two left in Emmitsburg to guard the left rear of the army, while the rest of General Daniel Sickles’ III Corps marched toward the battlefield.

Arriving at about 10 o’clock on the morning of July 2, de Trobriand’s brigade was posted that afternoon facing southwest on the wooded Stony Hill, midway between Graham’s brigade at the Peach Orchard and Ward’s brigade near Devil’s Den.

About 4:30 that afternoon, CSA General John Bell Hood’s division sprang out of the woods to the southwest and savagely attacked the southern end of USA General David Birney’s line. After detaching three regiments to General Birney for emergency duty nearer the flanks, de Trobriand stoutly defended his position with the three regiments he had left, holding off numerous insistent attacks by two Confederate divisions, even after the support on both sides had fallen back.

Finally, after losing nearly half of his men, he was relieved by General Samuel Zook’s Brigade of the III Corps. De Trobriand and his remaining men moved to the rear and bivouacked east of the Taneytown Road. General Zook was one of the first to be killed at the place where he had relieved de Trobriand. De Trobriand’s shattered brigade, was put in reserve on July 3, and supported some batteries but did no fighting themselves.

After Gettysburg, the Third Brigade was involved in the fighting at Manassas Gap on July 23, at Auburn on October 13, and on November 7 at Kelly’s Ford, where the operations of the brigade opened the way for three Army Corps for a general advance. For this success, general orders from headquarters conveyed the compliments of the General-in-Chief and the thanks of the President.

After Gettysburg, General Birney wrote:

Colonel de Trobriand deserves my heartiest thanks for his skillful disposition of his command by gallantly holding his advanced position until relieved by other troops. This officer is one of the oldest in commission as colonel in the volunteer service, had been distinguished in nearly every engagement of the Army of the Potomac, and certainly deserves the rank of brigadier general of volunteers, to which he has been recommended.

De Trobriand had shown at Gettysburg that he deserved permanent command of a brigade, but there was no immediate official response to Birney’s recommendation. De Trobriand continued to lead his brigade as a colonel through the fall campaign.

17th Maine Monument

17th Maine Monument

One of the most beautiful regimental monuments at Gettysburg National Military Park, the 17th Maine served in de Trobriand’s brigade in the Third Corps stands on de Trobriand Avenue. The granite monument was dedicated on October 10, 1888. It represents the stubborn fight the men of the 17th Maine made behind a stone wall on the edge of the Wheatfield. The monument stands at the spot where the colors of the regiment stood on July 2, 1863. Close inspection reveals trampled wheat beneath his feet. The monument also contains inset diamonds in red granite — symbols of the first division of the Third Corps. This is the most expensive Maine monument at Gettysburg; the total height is 20.5 feet.

On November 22, 1863, de Trobriand was not confirmed as Brigadier General by the Senate, although he was recommended by all of the officers above him. He was mustered out of service at his own request until his promotion was approved on January 5, 1864, and commanded the defenses of New York City (First Division, Department of the East) from May until June of that year.

De Trobriand was then ordered back to the Army of the Potomac in command of the First Brigade, Third Division, II Corps, troops formerly belonging to the Third Corps.

With them, he served during the final days of the war. He was at Deep Bottom, Petersburg, Hatcher’s Run, and Five Forks, and was at the head of a division in the operations that ended in General Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865. De Trobriand was promoted to major general that same day. He was mustered out of service January 15, 1866.

Supposing that his services would not be called for again, de Trobriand returned to France to write his recollection of Four Years With the Army of the Potomac for the information of the French people. (This publication was later translated into English.) In July 1866, he was commissioned a colonel in the Regular US Army, but he was in Paris, and remained there until his book was finished. The two-volume set was published in 1867 and 1868, and won high praise.

De Trobriand reported for duty later in 1866, and took command of the District of Dakota at Fort Stevenson. His mission was to keep the peace, and his time there was uneventful except for a few minor incidents. He was there for three years, during which time he kept a diary, which again was first published in French and later translated into English. This Diary, Military Life in Dakota, is much prized by Dakota historians.

In 1869, he was reassigned to the command of the 13th Infantry of the District of Montana stationed at Fort Shaw. Under this command, he was forced to deal with the hostile and murderous tribe of Piegans practically wiping out the complete tribe. This made the people of Montana happy as peace was restored to their land; however, history has not dealt too kindly with this campaign.

In 1870, the 13th was ordered to proceed to Camp Douglas, Salt Lake City, Utah to deal with the trouble that seemed to be brewing with the Mormons. De Trobriand and Brigham Young maintained a mutual respect for each other, which did not set well with the territorial politicians because they could not manipulate de Trobriand during the conflict between the US courts and the Mormon people.

By the direct orders of President Ulysses S. Grant, not his military superiors, de Trobriand was transferred to the Wyoming District at Fort Steele. In 1871, de Trobriand took over his new command, which, like the one in the Dakotas, was also uneventful.

On January 4, 1875, de Trobriand was ordered to New Orleans, where trouble was brewing. The Louisiana Legislature had forcibly removed the duly elected Governor (Kellogg) and his government. President Grant sent several regiments, including the 13th, to restore Governor Kellogg. De Trobriand did as he was ordered, and he did it in such a way that he earned the respect of those on both sides of the conflict.

In 1874, de Trobriand’s cousin died, so he succeeded to the title of Count. While the general lived quietly for the rest of his life, the countess lived lavishly in Paris.

Retiring from the military in 1879 with the rank of brigadier general, De Trobriand made New Orleans his home, while spending his summers alternating between visits to one daughter in France and another on Long Island, New York.

General Philippe de Trobriand died in Bayport, Long Island, on July 15, 1897, at the age of 81, and was buried in St. Anne’s Cemetery in Sayville, New York.

Mary Mason Jones de Trobriand died in July 1907, at her daughter’s home in Brest, France.

SOURCES

Familial History

Regis de Trobriand

Philippe Regis De Trobriand

In the Peach Orchard at Gettysburg

The Countess de Trobriand 1819-1907

Brevet Major General Regis de Trobriand

The Wheatfield – Gettysburg Pennsylvania

Philippe Regis Denis de Keredern de Trobriand

The Generals of Gettysburg: The Leaders of America’s Greatest Battle by Larry Tagg. Colonel Philippe Regis Denis de Keredern de Trobriand

The 110th Regiment in the Gettysburg Campaign