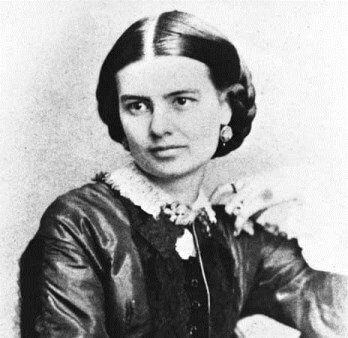

Wife of Union General Arthur MacArthur, Jr.

Mary Pinkney Hardy MacArthur was the wife of Arthur MacArthur, Union general and Medal of Honor recipient for his actions at the Battle of Missionary Ridge, and the mother of General Douglas MacArthur, one of the most highly decorated American soldiers in World War I and supreme allied commander of the Southwest Pacific Theater during World War II, reaching the rank of a five-star General of the Army.

Mary Pinkney Hardy MacArthur was the wife of Arthur MacArthur, Union general and Medal of Honor recipient for his actions at the Battle of Missionary Ridge, and the mother of General Douglas MacArthur, one of the most highly decorated American soldiers in World War I and supreme allied commander of the Southwest Pacific Theater during World War II, reaching the rank of a five-star General of the Army.

Image: Mary Pinkney Hardy MacArthur

With son West Point Cadet Douglas MacArthur, 1899

Mary Pinkney Hardy, always known as Pinky, was born on May 22, 1852, at her family’s plantation, Riveredge, just outside of Norfolk, Virginia. Her father, Thomas Asbury Hardy, migrated to Norfolk in 1829 from Currituck, North Carolina, in the northeastern corner of that state. He started several businesses with his brother, and was a prominent local businessman when he purchased the Riveredge estate in 1847. The ancestors of her mother, Elizabeth Margaret Pierce, had been residents of Norfolk since the Revolutionary War.

Born on June 2, 1845 in Chicopee, Massachusetts, Arthur MacArthur, Jr. and his family moved in 1849 to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, the city he would always call home. There his father, Arthur MacArthur, Sr., a Scottish immigrant, achieved success as a lawyer, politician and judge. Throughout his life, Arthur Sr. would use his political influence to assist his son in his military career.

MacArthur in the Civil War

With the coming of the Civil War, Arthur was determined to play his part, despite his father’s efforts to protect him. Arthur Sr. withheld permission for Jr. to enlist until Jr. agreed to return to the military academy he had been attending, while his father attempted to get him an appointment to West Point.

When the earliest appointment available would be in 1863, Arthur Jr. could no longer be denied permission to enlist. The 24th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry was being formed and Judge MacArthur’s influence and a lie about his age combined to obtain Arthur’s appointment as adjutant. His youthful appearance and juvenile mistakes made his training period a rocky start to his military career.

Eventually the 24th Wisconsin did get into the action. After early encounters at Perryville in Kentucky and Murfreesboro in Tennessee, the 24th moved on to Chattanooga, Tennessee. On November 24, Hooker’s command succeeded in the Battle of Lookout Mountain and prepared to move east toward CSA General Braxton Bragg’s left flank on Missionary Ridge.

The Miracle of Missionary Ridge

Arthur MacArthur, an eighteen-year-old lieutenant in the 24th Wisconsin Infantry, was at home on sick leave in Milwaukee, and hurried by train to rejoin his unit for the Battle of Missionary Ridge. MacArthur spent November 24, 1863, at the base of that ridge.

At 10 o’clock on the morning of November 25, 1863, the 150 men of the 24th were ordered to move forward a quarter mile to the edge of the woods forming the no-man’s land separating the two armies. In their front the ridge rose almost 600 feet, broken by ravines, gullies and enemy rifle pits.

In the afternoon, General Ulysses S. Grant ordered General George H. Thomas‘ Army of the Cumberland to move forward and seize the line of Confederate rifle pits on the valley floor, and stop there to await further orders. At about three o’clock, the siege guns signaled the advance. After moving out, the 24th Wisconsin charged three-quarters of a mile to the base of the ridge, and quickly sent the Confederates from the first line of rifle pits fleeing up the hill.

What happened next has become known as the ‘Miracle of Missionary Ridge.’ After routing the enemy from the first line of defenses, the victorious Union troops were subjected to a punishing fire from the Confederate lines up the ridge. Seeing the danger but unwilling to retreat, Arthur MacArthur led the 24th Wisconsin in a charge up the ridge without waiting for orders.

Back on Orchard Knob, an angry Grant wanted to know who had ordered the attack, but it quickly became clear that nobody had issued any such orders, and all Grant could do was watch. Using natural cover, regiment by regiment the Union soldiers began to advance up the ridge.

Halfway up the ridge the color sergeant faltered. MacArthur grabbed the colors, waved them high, shouted “24th Wisconsin” and led the entire Union line up the hill. After a canister explosion blew his hat off and tore the flag, MacArthur again waived the flag and led his men further up the hill.

Pistol in one hand and flag in the other, MacArthur planted the regimental flag on the crest of Missionary Ridge at a particularly critical moment, shouting, “On Wisconsin!” He was the first Union soldier to reach the top of Missionary Ridge, after an hour of very heavy fighting.

Once on top of the ridge, the 24th Wisconsin were able to seize Confederate guns and use them to fire on the enemy. All along the Confederate line the Southerners panicked and fled. MacArthur and his regiment were later complimented by General William Tecumseh Sherman.

The Army of the Cumberland’s ascent of Missionary Ridge was one of the war’s most dramatic events. A Union officer remembered:

Little regard to formation was observed. Each battalion assumed a triangular shape, the colors at the apex. … [a] color-bearer dashes ahead of the line and falls. A comrade grasps the flag. … He, too, falls. Then another picks it up … waves it defiantly, and as if bearing a charmed life, he advances steadily towards the top …

The last flag-bearer mentioned in the above quotation was Arthur MacArthur. The regiment’s commander, Major Baumbach, included in his official report of the battle:

Among the many acts of personal intrepidity on that memorable occasion, none are worthy of higher commendation than that of young MacArthur… He was the most distinguished in action on a field where many in the regiment displayed conspicuous gallantry, worthy of highest praise.

The next dramatic stand for the 24th Wisconsin would be at the Battle of Franklin, Tennessee. On November 30, 1864, the 24th was assigned to a resting area behind the front lines, secure in the belief that no attack would be coming that day. From a distance of 300 yards, the 24th heard increased fire, but paid it no heed until retreating Union troops ran through the campgrounds, followed by the sound of the Rebel Yell.

MacArthur was soon in the saddle, giving the order “Stand fast 24th!” Seven regiments, without orders, drew up into a battle line. MacArthur was in front of them with a pistol in one hand and a saber in the other yelling “Give them hell, 24th!” The line stopped the Confederate charge, threw the attackers back and saved the Union army from disaster.

Before the battle was over, MacArthur would be hit by musket balls just below the left knee and in the shoulder near the clavicle. After the fighting stopped, the men found MacArthur. After two weeks in a Nashville hospital, MacArthur was returned to Milwaukee for further recuperation. He was brevetted to the rank of colonel in the Union Army the following year, and became nationally recognized as ‘The Boy Colonel.’

Image: General Arthur MacArthur, Jr.

With the conclusion of the Civil War in 1865, MacArthur resigned his commission and studied law. After just a few months, however, he resumed his career with the Army. He was recommissioned on February 23, 1866 as a second lieutenant in the Regular Army. He was promoted to captain in September of that year, and would remain a captain for the following two decades, as promotion was slow in the small peacetime army.

When Pinky Hardy met MacArthur in New Orleans in 1874, she knew there might be some dissent about a Southern lady marrying a veteran of the Union Army. A proper Southern belle, Pinky was proud of her four brothers who fought In the Confederate Army, and her family was less than pleased when she announced their engagement.

Nevertheless the two were married at Riveredge, the Hardy family estate, on May 19, 1875. There is some indication that her brothers refused to attend the wedding, and that the only Southern minister who would agree to perform the ceremony was Reverend Matthew O’Keefe of St. Mary’s Catholic Church.

Between 1875 and 1884, Captain Arthur and Pinky completed assignments in Pennsylvania, New York, Utah Territory, Louisiana and Arkansas. During this time three children were born:

Arthur MacArthur III (born on August 1, 1876 – died 1923 of Appendicitis)

Malcolm MacArthur (born October 17, 1878 – died 1883 of measles)

Douglas MacArthur, born January 26, 1880, in Little Rock, Arkansas

Life on isolated army posts like the one at Ft. Selden, New Mexico, must have been difficult for a woman raised in Southern high society, trying to raise young boys. One friend commented that “in my picture of her there is a lot of white muslin dress swishing around and a blaze of white New Mexican sunlight, and in the midst of it this slender, vital creature that I have never forgotten.”

But in these years Pinky’s strong will and toughness became apparent. Her greatest trial was when her middle son, four-year-old Malcolm, died of measles in New Mexico in 1883. In his Reminiscences, her son Douglas would write that this loss was “a terrible blow to my mother, but it seemed only to increase her devotion to Arthur and myself.”

In these early years his father was the figure on which Douglas would model himself, but his mother played an equally important role.

My mother, with some help from my father, began the education of her two boys. Our teaching included not only the simple rudiments, but above all else a sense of obligation. We were to do what was right no matter what the personal sacrifice might be. Our country was always to come first.

Every night at bedtime throughout his childhood, young Douglas heard his mother say: “You must grow up to be a great man – like your father and Robert E. Lee.”

In 1886, Captain MacArthur was assigned to Ft. Leavenworth, Kansas, where Pinky could finally introduce her boys to life back in “civilization.” In 1889 MacArthur was promoted to major and transferred to the Adjutant General’s office in Washington, DC.

Arthur MacArthur was a lieutenant in the 24th Wisconsin Infantry when he earned the Congressional Medal of Honor for his valor in battle at Missionary Ridge. It was issued to him on June 30, 1890, and the citation reads:

Seized the colors of his regiment at a critical moment and planted them on the captured works on the crest of Missionary Ridge.

In January 1900, MacArthur was appointed Brigadier General in the regular army and was appointed military governor of the Philippines. However, MacArthur clashed frequently with Civilian Governor William Howard Taft. So severe were his difficulties with Taft that MacArthur that he eventually returned to the U.S. and commanded the Department of the Pacific, where he was promoted to Lieutenant General.

In many ways, Pinky’s relationship with her youngest son became the dominant factor in the latter half of her life. In 1898, with her husband fighting a war half a world away in the Philippines, Pinky lived near Douglas at West Point, where her prodding and encouragement would help him finish first in a class of 93 cadets in 1903.

With the coming of peace, General MacArthur was approved to take a grand tour of Asia with his wife and son Douglas. The tour ran from November 1905 through June 1906. The general reviewed the military forces of eleven countries, and the family were treated like royalty.

Back in the U.S. in 1906 the position of Army Chief of Staff became available and MacArthur was then the highest ranking officer in the Army as a lieutenant general (three stars). However, he never realized his dream of commanding the entire Army, but was passed over by then-Secretary of War William Howard Taft.

In April 1909 General MacArthur was relieved of command of the Department of the Pacific; he retired from the Army on June 2, 1909, the day he turned 64.

MacArthur went home and finally had time to enjoy the social life of Milwaukee. He attended a reunion of his Civil War unit there on September 5, 1912. While addressing the men he had led into battle fifty years before, he suffered a heart attack and died at age 67. He was buried in Milwaukee, but was moved to Section 2 of Arlington National Cemetery in 1926, where he is buried among other members of his family.

After the death of her husband and the premature death of her eldest son Arthur in 1923, Pinky became even closer to Douglas. She repeatedly lobbied army officials to give Douglas promotions. In 1925, she wrote a fawning letter to Army Chief of Staff John J. Pershing, imploring him to “be real good and sweet – the ‘Dear Old Jack’ of long ago…and give my boy his well earned promotion.” The peerless army wife had become a formidable army mother.

Pinky also meddled in Douglas’ personal life. When he married the attractive (but divorced) Louise Cromwell Brooks in 1922, Pinky did not approve. She expressed her disapproval by refusing to attend the wedding. She also confined herself to bed, feigning illness. The couple divorced in 1929.

Mary Pinkney Hardy MacArthur died at age 83 on December 3, 1935, while living with Douglas. She was buried with her husband in Section 2 of Arlington National Cemetery. Douglas was crushed. His aide Dwight Eisenhower wrote that her passing “affected the General’s spirit for many months.”

General Douglas MacArthur became one of the most highly decorated American soldiers in World War I. He served as chief of staff of the army under two presidents. In 1937, he retired and became field marshal of the Philippine Army only to return to active duty in 1941. During World War II, he served as general of U.S. Army Forces–Far East and was later appointed supreme allied commander of the Southwest Pacific Theater, reaching the rank of a five-star General of the Army.

The mayor of Norfolk approached General MacArthur on November 28, 1960, with a proposal to renovate Norfolk’s 1850 courthouse as a memorial to the General as well as a repository for his papers and possessions. In response, MacArthur was quoted as having said:

As Virginian myself, whose mother came from a long line of Virginians and whose mother and father were married in the present City of Norfolk, I accept as a great honor the invitation of the city to place my papers, decorations, and other mementoes of my military service in its perpetual care and keeping.

MacArthur requested that he and his wife be buried at the Memorial. MacArthur died April 5, 1964, at age 84 at the Walter Reed Army Hospital in Washington, DC, and is buried in Norfolk, Virginia.

During the Victorian era in which she was raised, women like Pinky MacArthur were more often judged by the achievements of their husbands and sons than by their own. Applying this standard, Mary Pinkney Hardy MacArthur – wife of a highly accomplished General and mother of one of the greatest soldiers in American history – was surely one of the more successful women of her day.

SOURCES

Battle of Missionary Ridge

Wikipedia: Arthur MacArthur, Jr.

Wikipedia: Battle of Missionary Ridge

My father’s aunt, Sally G Hardy once showed us kids a letter from general Douglas Macarthur which I remember. It started out “Dear Pinky”. I was only about 9 yrs old or so and don’t remember much more than that. My great aunt’s family, the Hardy family had a big family home in Lenoir county North Carolina built in 1808. In 1838 it was acquired by the Hardy family. The home was occupied during the war between the states by union soldiers and some of them were repelled by Mrs Sarah Hardy who threw hot water on the invaders. I have the newspaper clipping about the home titled: Home Base of Widespread Hardy Family. Kinston, April 13 1950.

We inherrited her table from Arthur’s time in the Phillipines, it is unclear if they ever had a chance to use it given his abrupt exit, but it was shipped back to the States in an old Clipper Ship. Beutifully hand crafted without nails.