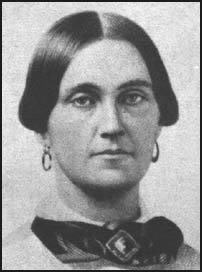

Accused Conspirator in the Lincoln Assassination

Mary Elizabeth Jenkins was born in May or June of 1823 near Waterloo, Maryland. She had two brothers. Her father died when she was two years old. Mary was then enrolled at a private girl’s boarding school, Academy for Young Ladies, in Alexandria Virginia.

Mary Elizabeth Jenkins was born in May or June of 1823 near Waterloo, Maryland. She had two brothers. Her father died when she was two years old. Mary was then enrolled at a private girl’s boarding school, Academy for Young Ladies, in Alexandria Virginia.

She married John Harrison Surratt in 1839, when she was sixteen and he was twenty-seven. The couple lived on lands that John had inherited from his foster parents, the Neales, in what is now a section of Washington DC known as Congress Heights. They had three children.

In 1851, a fire destroyed their home. The couple bought a farm and established a tavern and later a post office. The tavern was in operation by the fall of 1852, and by 1853 the family was living in the newly-built Surratt House and Tavern.

Surrattsville

On December 6, 1853, John bought the property that would later become Mary’s boardinghouse. He was appointed postmaster on October 6, 1854, and served in that capacity until his death in August of 1862. The surrounding area was called Surrattsville, Maryland, which was thirteen miles southeast of Washington, DC.

In October 1864, Mary rented the Surrattsville tavern and farm to a man named John Lloyd, a former Washington policeman. She and her daughter Anna moved to the Washington DC property her husband had purchased a decade earlier, and set up an eight-room boarding house.

Mary’s son, John, had become a Confederate spy and messenger during the Civil War, and met John Wilkes Booth, who became a frequent visitor at the boardinghouse. Other people, later identified as coconspirators, also visited there.

On April 11, 1865, Mrs. Surratt made a trip to Surrattsville with Louis Weichmann, one of her boarders. There they met John Lloyd. According to Lloyd, Mary told him the shooting irons would be needed soon—referring, he said, to two repeating carbines and seven revolvers that she had bought and stored on her property.

On April 14, 1865, the day of the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln, Mary made another trip to Surrattsville. Again Weichmann accompanied her in a hired buggy. She said that the purpose of the trip was to collect overdue rents from John Lloyd, but he later testified that she gave him a package containing John Wilkes Booth’s field glasses.

After assassinating President Lincoln at Ford’s Theater that night, Booth and his accomplice David Herold stopped at the Surrattsville tavern. Lloyd gave them whiskey, the pistols, and the field glasses. From there, the assassins traveled south, helped by many of the Southern sympathizers who had aided John Surratt in his activities as a courier for the Confederacy.

Booth Conspirator?

On the night of April 17, 1865, officers arrested Mrs. Surratt. She claimed total innocence, but while she was being questioned by police in her boarding house, Lewis Paine—real name Lewis Powell—who had attempted to assassinate Secretary of State William Seward, appeared at her door. Although witnesses testified she had met Powell several times, she denied ever having seen him before, and that didn’t help her cause.

She was charged with conspiracy and aiding the assassins in their escape. For two weeks after her arrest and before her trial, she was held on board a warship. Her cell had only a straw pallet and a bucket. Her head was enclosed in a padded canvas bag to prevent a suicide attempt. She was manacled, and constantly guarded by four soldiers.

During the trial, a newspaper described Mary Surratt as a rather attractive five-foot-six-inch buxom forty-year-old widow. She was the only woman conspirator and the oldest one. She and Lewis Powell received the most media attention. Powell always maintained that Mrs. Surratt was totally innocent.

Mrs. Surratt was tried along with seven men. In court, she dressed in black, with her head covered in a black bonnet. Her face was mostly hidden behind a veil. John Wilkes Booth’s diary contained evidence that he had planned to kidnap, not murder, the president, but changed his mind on the last day. It is highly unlikely that Mary could have known that, and she might not have been guilty of conspiracy to commit murder. But the court refused to admit Booth’s diary into evidence.

Mary was convicted on the testimony of John Lloyd and Louis Weichmann. She was found guilty of treason and conspiracy to commit murder by the military court, but the judges recommended that her sentence be life in solitary confinement in a penitentiary. President Andrew Johnson maintained that he never saw the plea for mercy, but Judge Advocate Joseph Holt said he was present when Johnson read the plea. Whatever the case, the president signed her death warrant, saying that she had “kept the nest that hatched the egg.”

Even the hangman didn’t think the government would hang a woman. In his personal account, he stated, “The night before the execution I took the rope to my room and there made the nooses. I preserved the piece of rope intended for Mrs. Surratt for the last. By the time I got at this I was tired, and I admit that I rather slighted the job. Instead of putting seven turns to the knot—as a regulation hangman’s knot has seven turns—I put only five in this one. I really did not think Mrs. Surratt would be swung from the end of it, but she was, and it was demonstrated to my satisfaction, at least, that a five-turn knot will perform as successful a job as a seven-turn knot.”

Hangman’s Noose

At noon on July 6, Mary Surratt was informed that she would be hanged the following day. She wept profusely. She was joined shortly by a Catholic priest, her daughter Anna, and a few friends. She was allowed to wear looser handcuffs and leg irons during this period, but was kept hooded. She spent the night praying and refused breakfast. Her friends were ordered to leave her at 10:00 that morning, and her heavy manacles were replaced. She spent the final hours of her life with her priest.

On July 7, 1865, around 1:15 pm, a procession consisting of the four prisoners—Mary, Lewis Powell, and two other male conspirators—and many guards were led through the courtyard. Their hands manacled and their legs chained with heavy irons and 75-pound iron balls, the condemned walked past their own graves, and up the thirteen steps to the gallows.

Mrs. Surratt wore a long black tightly corseted dress and black veil, and had to be supported by two soldiers. She was seated in a chair while her chains and shoes were removed. Her wrists were tied behind her, her arms were bound to her sides, and her ankles and thighs were tied together, using white cloth instead of rope.

The noose was placed around her neck, and a thin white cotton hood was placed over her head. The hood was not a mercy for the condemned, as she could easily see through it, but to prevent the spectators from seeing her lolling tongue and blue face as she died. Over one thousand men, women, and children had come to watch her die.

The Show Must Go On

General Winfield Scott Hancock read out the death sentences in alphabetical order. He then clapped his hands three times, and four members of the Fourteenth Veteran Reserves knocked out the supporting post releasing the platform.

The conspirators dropped five to six feet, which proved insufficient to break their necks. Mrs. Surratt appeared to have been knocked unconscious by the fall and the effects of the rope. She died relatively quickly, and only strained slightly against her restraints and made wheezing and gagging noises for less than three minutes.

Mary Jenkins Surratt was pronounced dead and cut down at 2:15 pm, the first woman to be executed by the United States government. She was 42 years old. Her last words, spoken to the guard who put the noose around her neck, were “please don’t let me fall.”

Her body was stripped naked (the clothes were given to charity), wrapped in a sheet, and placed in a simple pine coffin with a glass vial containing her name to help identify the body. She was then buried in a shallow grave next to the prison walls. Several pieces of the rope that had ended her life and locks of her hair were sold as souvenirs.

Mary’s son, John Surratt, was arrested in Europe two years later and returned to the United States for trial. He admitted that he was actively involved in an earlier plot to kidnap President Abraham Lincoln, but claimed he was not involved in his assassination. He testified that his mother had not been involved in either plot. He was released after the judge was forced to declare a mistrial—eight jurors voted not guilty, four guilty.

In 1869, Anna Surratt made a successful plea to the government for her mother’s remains, which she buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery in Washington DC. Anna and Isaac Surratt were later buried beside their mother. John Surratt was buried in Maryland. John Lloyd, whose testimony led to Mary’s conviction, is buried less than 100 yards south of her in the same cemetery.

Oh well did these 4 conspirators get their justice rewards? I’d say so but Mary claimed her innocence. No doubt in the end it was a hung jury. I didn’t realise Winfield Scott Hancock read out the death sentences.