Women in the Border State of Maryland

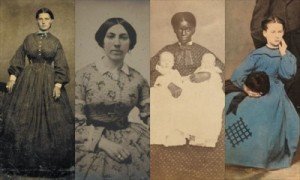

Many Maryland women made significant contributions to the Union war effort. As a border state having both slaves and free African American women, Maryland was divided in sentiment between the Union and the Confederacy. The most famous conductor on the Underground Railroad, Harriet Tubman was also an escaped slave from Maryland’s Eastern Shore.

Many Maryland women made significant contributions to the Union war effort. As a border state having both slaves and free African American women, Maryland was divided in sentiment between the Union and the Confederacy. The most famous conductor on the Underground Railroad, Harriet Tubman was also an escaped slave from Maryland’s Eastern Shore.

Harriet Tubman also served as a Union nurse and spy, and she was the first woman to lead an armed expedition. In June 1863, she guided three steamboats around Confederate mines in the waters surrounding Port Royal, South Carolina in the Combahee River Raid, which liberated more than 700 slaves.

Anna Ella Carroll played a significant role as advisor to President Abraham Lincoln and his cabinet during the war. After a reconnaissance mission, Carroll advised the War Department that they change their invasion route from the Mississippi to the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers, resulting in the surrender of Fort Henry and Fort Donelson in February 1862, the first important victories in the Western Theater.

Unsung Heroes of Maryland

Women who lived in Maryland had unique perspectives on the Civil War. Maryland represented a microcosm of the national conflict. Maryland women in the Civil War witnessed troop movements, cavalry raids and battles in their towns which were more typical of a Confederate state, but they also had a shared experience with women in those states that remained in the Union.

Most women’s lives were centered around the household and family. However, social changes initiated by the war offered women the opportunity to take leadership roles at home while their husbands and fathers were away. They became more involved in public arenas such as politics and social welfare. More affluent women also engaged in voluntary activities on the home front that proved vital to both sides. They formed aid societies to provide soldiers with clothing and other supplies

An Appeal for Peace was a broadside (poster) from the “Women of Maryland” to Union army General-in-Chief Winfield Scott, dated July 4, 1861; it was a plea to end the conflict before much bloodshed occurred. Ironically, this appeal was dated the same day President Lincoln secured a twenty five percent Congressional increase in both funding and troop levels in support of the Union cause.

Though they “claim, to know no distinction in party broils,” the “Women of Maryland” who authored this broadside displayed clear Confederate sympathies in their appeal. By exalting the “good and noble” Confederate General Robert E. Lee, as well as P.G.T. Beauregard and Joseph E. Johnston, the “Women of Maryland” championed peace as a way to preserve states’ rights and to uphold a non-coercion policy for those states that wished to secede.

Jennie and Hettie Cary

In April 1861, Maryland native John Ryder Randall read the news about the riots in Baltimore, the first blood shed in the Civil War. A secessionist living in Louisiana, Randall wrote a poem in support of Maryland and the Confederacy. My Maryland was published in several newspapers, and Baltimore society sisters Jennie and Hetty Cary decided to set Randall’s poem to music.

The sisters chose the tune O Tannenbaum and slightly modified the wording of the poem. Their song, Maryland, My Maryland quickly became a rallying cry for Marylanders and Confederates alike. The Cary sisters, however, are not named on the original sheet music and neither is Randall. This omission could have had less to do with gender issues, and more to do with the precarious position of secessionists in Maryland, for whom anonymity meant greater safety.

Before the war, women composers went largely unacknowledged and female authorship was indicated on music covers as merely by A Lady. During and after the war, women emerged as composers, singers and arrangers of popular music. Women who wished to contribute to the war effort and demonstrate their patriotism found an opportunity to do so by printing their names on their compositions.

Angela Kirkham Davis

Author Angela Kirkham Davis lived in Funkstown, Maryland, near Boonsboro. She wrote War Reminiscences: A Letter to My Nieces, which describes her experiences during and after the Battle at Antietam, which took place not far from her home. She relates the tensions as well as the friendships between the “Secessionists” and the “Yankees” in her town and the divisions that took place within families and among friends.

Davis describes the Union encampments she visited, the phenomena of Union soldiers marching through her town, and the influx of freed slaves from Virginia. Angela Kirkham Davis’ narrative of her personal experiences of the horrors of war and the effect it had on the citizen population expresses the cruel reality of war in a border state that supported both sides.

Frederick, Maryland was occupied by General Robert E. Lee‘s forces in early September 1862, and the Confederates flooded through town. On September 16, General George B. McClellan confronted Lee near Sharpsburg, defending a line to the west of Antietam Creek. At dawn on September 17, General Joseph Hooker‘s I Corps mounted a powerful assault on Lee’s left flank that began the bloody Battle of Antietam.

Attacks and counterattacks swept across the Miller Cornfield and the woods near the Dunker Church. At a crucial moment, General A.P. Hill‘s division arrived from Harpers Ferry and counterattacked, saving Lee’s army from destruction. Although outnumbered two to one, Lee committed his entire force, while McClellan sent in only four of his six available corps. This enabled Lee to shift brigades across the battlefield and counter each individual Union assault, but he was ultimately defeated.

The Battle of Antietam was the single bloodiest day of the Civil War, claiming the lives of more than 23,000 soldiers killed, wounded or missing in action. After the fighting was over, Angela Davis took food to the battlefield, where she comforted the wounded and dying. Although a Union supporter, Davis provided water for Confederate as well as Union troops. When asked why, she replied, “Because our Heavenly Father taught us to give a cup of cold water, even to our enemies.”

Mary Quantrell – Not Barbara Fritchie

In 1863, John Greenleaf Whittier wrote the poem Barbara Fritchie about a woman’s courageous act of flying the Union flag from her attic window above of the heads of Confederate soldiers as they marched through Frederick, Maryland en route to the Battle of Antietam in September 1862. Although ninety-six-year-old Barbara Fritchie was living in Frederick at the time, she was not the one who defiantly displayed the Union flag to antagonize General Stonewall Jackson, as the legend goes.

This is an excerpt from Barbara Fritchie:

“Shoot, if you must, this old gray head,

But spare your country’s flag,” she said.

A shade of sadness, a blush of shame,

Over the face of the leader came;

The nobler nature within him stirred

To life at that woman’s deed and word;

“Who touches a hair of yon gray head

Dies like a dog! March on!” he said…..

No firsthand account speaks of Fritchie being seen in public that day; in fact, she might have been bedridden. Fritchie’s strong Unionist views were never in doubt, however. She freely expressed her strong and unyielding support for the Union throughout the conflict. It is known that Barbara Fritchie stood outside her home and cheered on McClellan’s forces as they marched through Frederick a few days later.

According to eyewitnesses accounts, the brave flag-waver was Fritchie’s neighbor Mary Quantrell. In her late 30s at the time, Quantrell held up the Stars and Stripes on her porch while Confederate soldiers tramped down Patrick Street, according to seven witnesses cited in a book by a Frederick resident who respected Fritchie but wanted the truth to be told. Quantrell also had a verbal altercation with a Confederate officer, who was probably General A.P. Hill.

Virtually no one remembers Mary Quantrell because Fritchie was the one immortalized a year after the event by John Greenleaf Whittier. Disputes about the poem’s veracity arose almost immediately after it was published. Whittier was apparently misled by third-hand information he received from a fellow writer in Washington, DC.

Both Fritchie and General Jackson had died before the poem was written and were not available to set the record straight. True or not, Whittier’s poem became famous, and spawned books, plays, musicals, films and souvenirs of all types. His papers at Swarthmore College include an 1876 letter from Quantrell pleading with him to correct the record.

When Mary Quantrell died in 1879, both major Frederick newspapers identified her as the genuine inspiration for the ballad.

Sabers and Roses Ball

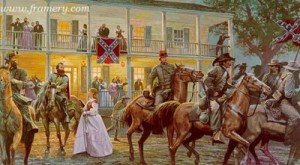

Early in September 1862, while General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia rested near Frederick, Maryland, Lee’s cavalry chief General J.E.B. Stuart occupied Urbana, Maryland to report on any Federal advance from Washington, DC. Stuart received a warm welcome from the community of Urbana, and with his usual flair decided his hard fighting horsemen needed a break from the war.

On September 8, 1862, General Suart hosted a dance at Landon House in Urbana for Confederate cavalrymen and the women of Urbana. The house was decorated with the cavalry’s regimental flags and the ballroom was adorned with roses clipped from nearby gardens. Southern belles from miles around dressed in their finest gowns, and the 18th Mississippi Cavalry regimental band provided the music.

During the ball, news arrived that Union soldiers were close by and on their way to Urbana. The Confederate horsemen rode off into the night. After learning that the 1st North Carolina Infantry had repulsed the Northern forces, they quickly returned and the dance that has come to be known as the Sabers and Roses Ball resumed.

During the Maryland Campaign, Landon House was converted into a field hospital where wounded and dying soldiers who were retreating to Virginia received care. It was likely at this time that so called “lightning sketches” of CSA President Jefferson Davis and General Stuart were drawn in charcoal by Rebel troops on a wall over one of the fireplace mantles.

Shortly thereafter, Federal troops also used Landon House as a hospital and seeing the drawings made by the Confederate troops, the Union soldiers added an even larger image of President Abraham Lincoln and signed and dated it September 16, 1862. These drawings are still visible on the walls of the house today.

Advancements for Women

The Civil War empowered some Maryland women to step outside of their traditional nineteenth-century gender roles. However, women’s involvement in the War did not cause a major shift in woman’s sphere, and gender roles remained largely unchanged immediately after the war. Although women had successfully held leadership positions in businesses or in hospitals, many women were forced to relinquish these roles to men who returned from the battlefield.

Most towns and communities in Maryland had formed relief societies or associations during, and women had taken the opportunity to learn organizational and management skills that would stand them in good stead after the war. In Frederick, fifty women established the Ladies’ Relief Association to obtain supplies needed to aid sick soldiers, and the women then made daily visits to hospitals to distribute the food, clothing, blankets and medical supplies.

After the war, some women used their war experiences to organize women’s associations in order to initiate social reforms. However, most women continued to be tied to the home and family, and without the right to vote or hold property, were considered second-class citizens. African American women had gained their freedom, but not much else. It would be decades before larger strides were made.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Landon House

Robert McCartney: Barbara Fritchie Did Not Wave That Flag

Women on the Border: Maryland Perspectives of the Civil War