Civil Unrest and Activism in the Confederate Capital

Image: North Carolina Emigrants: Poor White Folk, by James Henry Beard

During the Civil War, refugees like these traveled to Richmond hoping for a better life, but they only added to the overcrowding and lack of provisions that already existed there.

A group of working-class women gathered in Belvidere Hill Baptist Church in the Oregon Hill section of Richmond, Virginia on the evening of April 1, 1863. A few had traveled from the outskirts of the city to attend this meeting of working class women. One of the leaders, Mary Jackson, was a peddler and another woman sewed tents to support her family. The women decided to meet the following morning and demand food at reasonable prices from Virginia Governor John Letcher.

Backstory

By the spring of 1863 Richmond’s population had swelled to more than 100,000 – more than the city’s resources could support- resulting in high rents and exorbitant costs for the daily necessities of life. This economic burden affected the working class most – their wages could not keep pace with inflation. No one but the upper class could afford essentials like flour and sugar. The harsh weather in the winter of 1863 made the transport of food and fuel into the city almost impossible, which only added to an already volatile situation.

Discontent on the Home Front

The Confederate Army had won a great victory at Fredericksburg, Virginia in December 1862, but the performance of the military did not affect the lives of the citizens as much as the government’s domestic policies did. The influx of tens of thousands of refugees into Richmond had created a deficit of housing in the city and raised the prices of goods. Inflation had undermined the value of Confederate currency and made it difficult for civilians to provide for themselves and their families. By 1863, most citizens remarked that they found it almost impossible to get enough to eat.

On March 26, 1863, the Confederate Congress passed the Impressment Act, which allowed the government to seize food and fuel to support armies in the field. This new law, combined with rampant inflation and plummeting morale, caused citizens to begin hoarding supplies; within a short week, food and other daily needs were becoming scarce.

The women who met at the Belvidere Hill Baptist Church on the night of April 1 were desperate for a solution to the food shortage problem in the city. Mary Jackson, a 34-year-old mother of four who worked as a peddler, quickly became a leader, energizing the crowd with reports of the unbridled greed being practiced by speculators and merchants. They decided to take their demands to Governor John Letcher the next morning. The women promised to meet at Capitol Square the next day to seek a meeting with Virginia Governor John Letcher. Before they disbanded, Mary Jackson suggested that the women bring weapons to defend themselves – hammers, hatchets, whatever they had at home.

On the morning of April 2, 1863, these frustrated women gathered in Capitol Square around 9 o’clock and demanded to speak to Governor Letcher. They were greeted instead by his aide, Colonel Bassett French, who told them that Letcher was too busy to be disturbed. Rather than have them escorted away, French left the armed women, some with bayonets visible on their belts, angry and milling about the Capitol grounds. Most unusual.

As the crowd multiplied and decibels increased, Governor Letcher eventually appeared in Capitol Square and addressed the women, now numbering in the hundreds, now numbering in the hundreds. In answer to their first demand, he informed them that he could not mandate that goods be sold to them at reasonable prices. He ordered the women to disperse. When they refused to comply, he threatened to order the Public Guard to shoot into the crowd.

Angered by Governor Letcher’s speech, the women rushed out of Capitol Square and toward the business district. In his book A Rebel War Clerk’s Diary at the Confederate States Capital (1866), J. B. Jones wrote about that morning:

This morning early a few hundred women and boys met as by concert in the Capitol Square, saying they were hungry, and must have food. The number continued to swell until there were more than a thousand. But few men were among them, and these were mostly foreign residents, with exemptions in their pockets. About nine a.m. the mob emerged from the western gates of the square proceeded down Ninth Street, passing the War Department, and crossing Main Street, increasing in magnitude at every step, but preserving silence and (so far) good order. Not knowing the meaning of such a procession, I asked a pale boy where they were going. A young woman, seemingly emaciated, but yet with a smile, answered that they were going to find something to eat. I could not, for the life of me, refrain from expressing the hope that they might be successful…

The Riot

Dissatisfied with Letcher’s response, the women marched out of Capitol Square and headed toward Ninth Street and the city’s business district. The group rapidly transformed into an angry mob of rioters. Most carried weapons, which ranged from clubs and axes to knives and pistols. As they walked, they attracted hundreds – possibly thousands – of followers. The mob continued to increase in number as they proceeded down Cary Street, loading carts they stole along the way with shoes, cornmeal, flour, and other foodstuffs. They entered stores run by the speculators and emptied them of their contents.

Threadbare Garments

The rioters were accused of taking clothing, shoes and jewelry, items that were not necessary for their subsistence, but that was not always the case. By April 1863, many women were clothed in threadbare fabric that barely sufficed to cover their bodies. Shoes were also an almost unheard of luxury. Thus, the looting of clothing and shoe stores during the Richmond Bread Riot did not constitute rampant thievery as many of the accounts portrayed. Instead, the women seized goods which were a necessity for their survival and for their standing as respectable women. The trials of many participants confirmed the importance of clothing in Richmond society.

Image: Richmond before the war

Image: Richmond before the war

Looting Stores

The mob then began knocking down the doors of a Confederate commissary and government warehouses, seizing bacon, hams, flour and clothing. When they turned into Main Street, they found that the owners had closed and locked down their shops, but they broke in the plate-glass windows, demanding silks, jewelry and other expensive items. Streets became so crowded, it was impossible to determine the actual number of rioters; the average estimate was 5500 participants.

Graphic Description of Violence

In a letter from Hal Tutwiler to Nettie Tutwiler, April 3, 1863:

We have had a dreadful riot here yesterday, and they are keeping it up today, but they are not near as bad today as they were yesterday. But I will begin at the first. Thursday morning I went to the office as usual. A few minutes after I got in, I heard a most tremendous cheering, went to the window to see what was going on, but could not tell what it was about. So we all went down into the street. When we arrived at the scene we found that a large number of women had broken into two or three large grocery establishments, and were helping themselves to hams, middlings, butter, and in fact every thing they could find.

Almost every one of them were armed. Some had a belt on with a pistol stuck in each side, others had a large knife, while some were only armed with a hatchet, axe or hammer. As fast as they got what they wanted they walked off with it. The men instead of trying to put a stop to this shameful proceeding cheered them on and assisted them all in their power.

When they [the women] found that the guards were on Cary st. they turned around & went up on Main street and broke into several stores. In the morning before they began they went up to the Capitol, & Governor [John] Letcher made them a speech, but it was like pouring oil on fire.

After that the Prest. [Jefferson Davis] made them a speech, and while they were engaged in their robbery the mayor of the city [Joseph Mayo] came down to make them another. But it did no good. I think there were fully 5000 persons on Cary st., if not more, besides that many more on Main and Broad. This morning they began again but they were told that if they did not disperse they would be fired on.

One woman knocked out a pane of glass out of a shop window, of which the door was fastened, & put her arm in to steal something, but the shopman cut all four of her fingers off. I was right in the middle of the row all the time. It was the most horrible sight I ever saw…

Have heard how the riot ended this morning. Gov. Letcher told them he gave them five minutes to disperse and if they did not disperse he would have them fired on by the city guards. They immediately began to leave the streets and in a few minutes they were comparatively vacant. The stores have been closed for the last two days.

Virginia Governor Letcher appeared on the scene and gave the mob five minutes to disperse, threatening to use military force if they did not comply. They continued their madness until the Richmond Battalion arrived to protect the city from destruction.

J.B. Jones continues the tale:

About this time President Jefferson Davis appeared and urged the rioters to return to their homes. He told them that such acts would bring famine upon them in the only form which could not be provided against, as it would deter people from bringing food to the city. He seemed deeply moved; and indeed it was a frightful spectacle, and perhaps an ominous one, if the government does not remove some of the quartermasters who have contributed very much to bring about the evil of scarcity. I mean those who have allowed transportation to forestallers and extortioners.

All is quiet now (three P.M.); and I understand the government is issuing rice to the people.

The Aftermath

Authorities arrested forty-three women and twenty-five men who stood trial in Richmond courts during the following months. Several were fined, and others issued jail terms. According to the Richmond City Council minutes, the rioters damaged several businesses. On April 13, 1863 the minutes noted:

Accounts for the property taken by the late rioters in this City, one in the name of J. T. Hicks amounting to the sum of $13,530.00 and one in the name of Tyler & Son amounting to the sum of $6,467.55, were laid before the Council and referred to the Committee on Claims.

The Richmond City Council took several steps to prevent the outbreak of any riots in the future by placing cannon on Main Street and calling Confederate troops into the city.

The Richmond Bread Riot did bring about changes in policies regarding the poor. On April 13, 1863 the Richmond City Council passed An Ordinance For the Relief of Poor Persons Not in the Poor House, which established a free market and provided provisions and fuel. However, the ordinance clearly stated that it would provide relief only to the worthy poor. The unworthy poor were those individuals who had “participated in a riot, rout, or unlawful assembly.”

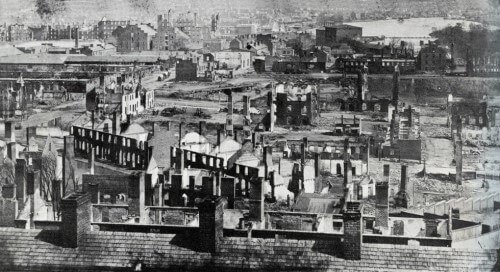

Image: Ruins of Richmond after the war, April 1865

On May 1, 1863, the Confederate government passed an exemption act that “gave Confederate officials another means to alleviate individual cases of poverty.” This act exempted individuals in areas that were “deprived of white or slave labor indispensable to the production of grain or provisions.” Essentially meaning that men who were necessary for the survival of their families were allowed to stay at home and continue farming.

For the most part, these acts did little to increase public morale. The Confederacy had already lost much of its support on the home front. The failure of the elite and the government to provide for its needy citizens contributed to civil unrest throughout the South.

Letters from Home

Another symptom of the Confederacy’s lack of support for the poor was desertion in the ranks of the Confederate Army. Many families of Southern soldiers would have benefited from poor relief. Proper support of soldiers’ families would have decreased desertions and greatly aided the war effort. Phoebe Yates Pember, matron at Chimborazo Hospital in Richmond, believed soldiers’ concerns about their families encouraged desertions. Here she paraphrases the letters she read to soldiers from their families:

Almost all of these letters told the same sad tale of destitution of food and clothing, even shoes of the roughest kind being too expensive for the mass or unattainable by the expenditure of any sum, in many parts of the country. … how hard for the husband or father to remain inactive in winter quarters, knowing that his wife and little ones were literally starving at home – not even at home, for few homes were left. The women refused to continue complying with the outrageous demands which the government placed on its citizens.

SOURCES

The Richmond Bread Riot

Encyclopedia Virginia: Richmond Bread Riot

A Rebel War Clerk’s Diary at the Confederate States Capital. By J. B. Jones

The Richmond Bread Riot of 1863: Class, Race, and Gender in the Urban Confederacy – PDF