She Found Her Place Among the Lowly

Image: Sallie Holley (left) and her lifetime companion Caroline Putnam

Sallie Howland and the Civil War

Sallie Holley, abolitionist and educator, spent her entire adult life working to free African Americans from bondage, and then teaching the former slaves how to improve their lives.

Early Years

Sarah Holley was born February 17, 1818 in Canandaigua, New York. Sallie, as she was called, was one of twelve children born to Myron and Sally House Holley. Her father was a minister and a Canal Commissioner, who worked to create the Erie Canal. His antislavery beliefs greatly influenced Sallie. After her father’s death in 1841, Holley taught school in Rochester for a short time.

While visiting a sister in Buffalo in 1843, Sallie Holley was impressed by a lecture given by former slave and abolitionist Frederick Douglass. Years later Douglass remembered meeting Holley for the first time. John White Chadwick included part of Douglass’ recollection in his biography A Life for Liberty: Anti-Slavery And Other Letters Of Sallie Holley:

An Anti-Slavery Convention was appointed to be held in Buffalo, New York … in the year 1843. The abolition question was then so unpopular that no church or public hall could be obtained in which to hold the meetings; so we went into an old deserted warehouse, without door or windows, and began with an audience of six or seven men who stood about the open front of the building. I continued for six days to speak in this place to an audience (which at last crowded the house) of the common people, who came in their common clothes.

On the third day of our motley meeting, made up entirely of men, I observed with some amazement, as well as pleasure, a stately young lady, elegantly dressed, come into the room, leading a beautiful little girl. The crowd was one that would naturally repel a refined and elegant little lady, but there was no shrinking on her part. The crowd did the shrinking. It drew

in its sides and opened the way, as if fearful of soiling the elegant dress with the dirt of toil.This lady came daily to my meetings in that old deserted building, morning and afternoon, until they ended. The dark and rough background rendered her appearance like a messenger from heaven sent to cheer me in what seemed to most men a case of utter despair. The lady was Miss Sallie Holley, and this story illustrates her noble, independent, and humane character. She was never ashamed of her cause nor her company.

In 1847, a Unitarian minister gave Holley $40.00 for expenses and encouraged her to attend Oberlin College. When her money was depleted, she worked at various jobs on campus. There she met Caroline Putnam, who would become her lifelong friend and constant companion.

Career in Activism

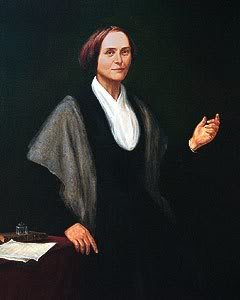

During her time at Oberlin, Sallie Holley’s choice of career was influenced by another lecture – this time by abolitionist Abby Kelley. After graduation in 1851, Holley became an agent of the American Anti-Slavery Society. The Society was founded in 1833 by William Lloyd Garrison and Arthur Tappan; by 1838 it had 1,350 local chapters and approximately 250,000 members. Notable female members included Lydia Maria Child and Lucretia Mott.

In addition to her work with the Society, Holley lectured regularly. One of her journals includes a list of places where she gave speeches in New York, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Maine, and Delaware. Caroline Putnam often accompanied her on the abolitionist speaker circuit. During this time, Holley also wrote for Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator.

Although she admitted to a fear of public speaking that never disappeared, Holley was an engaging speaker who drew large crowds. It was rare for a woman at that time to publicly advocate a cause, she endured the stigma that sometimes caused acquaintances to cross the street rather than speak to her.

Even after the Thirteenth Amendment freed all slaves on December 18, 1865, Holley continued working for their benefit by collecting clothing and lecturing. Word spread of a plan to discontinue the American Anti-Slavery Society, and Holley offered her opinion, which was published in the National Anti-Slavery Standard in 1868:

It is heartless, cold-blooded, worldly apathy, that can object to the name or the work of an Anti-Slavery Society. Since this New Year began, three Negroes were seized in Tennessee, bound over logs, and beaten nearly dead, because they voted the Republican ticket. Three thousand black men in Mississippi petition Congress to send them to Liberia. In their touching language, “The white people have all the land, all the money, all the education. Many of the planters refuse to pay us all together, and they work generally to prevent the education of our children.” And you tell me there is no need of an Anti-Slavery Society?

In 1868, Caroline Putnam volunteered to educate former slaves in remote Lottsburg, Northumberland County, on the Northern Neck of Virginia, about an hour and a half east of Richmond. After she lost her struggle to preserve the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1870, Sallie Holley joined her there at the age of 52.

Image: Beginnings of Black Education

Credit: Virginia Historical Society

Holley School

When Putnam expressed her wish to establish her own school where she might have more autonomy, Holley purchased the property on which the school would be built. Putnam named the school for her in appreciation. The operation of this school became Holley’s life’s work – and Putnam’s as well – teaching reading, writing, and vocational skills to African Americans.

Through the coming decades they lived at the Holly School, as Caroline named it, leaving one at a time for an annual trip North to visit family and friends and to beg funds and supplies from them. In a letter dated August 3, 1875, Holley describes the school and the home she had built for them:

Nothing could be more bare and blank, and hopeless than our material surroundings were to begin with. But upon a two-acre strip of this desolete land, … we have succeeded in building a cheerful Teacher’s Home, and a spacious, airy, pleasant new schoolhouse. We have made flower-borders, strawberry-beds, melon-patches, grape-arbors, and fruit trees to blossom and flourish, to the admiration of all around us.

There are seven hundred people in this town. Our school keeps [open] from Christmas to Christmas, without vacation, the year round. … Most of our scholars are intermittents, for they have to work nearly all summer in these immense cornfields. But by keeping the doors of school ever open, hundreds have learned to read and write.

When we first came, they did not know a letter of the alphabet or the names of the days of the week; and could not count on ten fingers or name the State they lived in. And the ignorance of these white Virginians, too, is appalling – a striking illustration of the truth of what the great [William] Wilberforce said: “No man can put a chain around his brother’s neck and God not put the other end of the chain about his own.”

These women were so dedicated to this work their lives became a self-imposed exile and martyrdom. White Southern communities ostracized Northerners who moved South to establish schools for the freedmen and freedwomen. Only letters and visits from their Northern friends and vacations relieved their isolation.

Image: Sallie Holley and Caroline Putnam, seated in front

Image: Sallie Holley and Caroline Putnam, seated in front

With the staff and students of the Holley School at Lottsburg, Virginia, circa 1890

To stave off the sense of isolation, Sallie Holley regularly traveled to New York City in January to visit friends, attend cultural events, and enjoy society once again. During one of these visits she became ill with pneumonia and died on January 12, 1893 at the age of seventy-four.

Caroline Putnam lived until 1917, and in her will she deeded the school and property to a board of trustees.

Legacy

Headed by Robert J. Diggs, the all-black board continued the educational legacy of the Holley School. In the first year after Putnam’s death, Holley School became a public institution; the land was leased to the Northumberland County School Board. However, Diggs and the other board members retained the deed and took responsibility for the continued operation of the school, which was by then segregated.

By the 1920s the black community of Lottsburg had outgrown the original building, and they raised money and provided the labor to construct the four-room schoolhouse that now stands, though it is no longer in use. The cornerstone bears the date 1869, when the land was purchased, as well as the year 1933 when present structure was completed.

The Holley School continued to operate for decades, instilling the principles of learning and discipline in its students. Some of those who were educated there later returned and worked as teachers at the school, continuing the legacy of academic achievement.

SOURCES

Holley Graded School

Sallie Holley (1818-1893) – PDF

Sallie Holley: Inspiration From Our History

Connecticut Historical Society: A Bright Star in the Family Constellation