Farm on the Gettysburg Battlefield

Joseph Sherfy purchased a fifty-acre farm along the Emmitsburg Road about a mile south of the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania in 1842. At the time of the battle, the farm included the famous Peach Orchard to the south of Wheatfield Road as well as both Big and Little Round Tops and the Devil’s Den.

Image: Photograph taken from the air above Cemetery Ridge, year unknown

Image: Photograph taken from the air above Cemetery Ridge, year unknown

Sherfy Farm buildings (upper left) and the Peach Orchard (lower right)

There were surely many peach orchards in America on July 2, 1863, but General Daniel Sickles’ troops defended these fields so valiantly that it will be forever known as The Peach Orchard.

Sherfy Family

Joseph and Mary Sherfy were pacifist members of the Church of the Brethren and Joseph served as a minister. In 1863, Otelia Sherfy and her sisters, Mary, and Anna were 18, 16, and 13 years old, respectively. The girls were considered too young to join a faith community that practiced adult baptism, as were their brothers Raphael, John, and Ernest.

Sherfy had planted much of his land in peach trees, and by the eve of the Civil War, he was selling his peaches fresh, dried, and canned. The business supported Joseph, his wife Mary, and their six children.

On the fateful morning of July 1, 1863, Joseph Sherfy and his sons drove their livestock to the southeast side of the Big and Little Round Tops, successfully hiding their animals from both armies. Joseph and Mary then sent their children to a farm behind Union lines, but they remained at the farm.

As the troops of the Union I Corps rushed north along the Emmitsburg Road, they found a large tub of water beside the road. Reverend Sherfy was working hard to keep the tub filled from his well while Mary baked bread, which the soldiers consumed as soon as it was cool enough to eat.

Battle of Gettysburg: July 1

On the morning of July 1, 1863, General John Reynolds commanded the I, III, and XI Corps of the Army of the Potomac, plus General John Buford‘s cavalry division. Buford had occupied Gettysburg and set up light defensive lines north and west of the town and then held off the approach of two Confederate infantry brigades on the Chambersburg Pike until the infantry arrived.

On a personal note, General Reynolds must have been happy with his life. While on duty in California in the late 1850s, he had fallen in love with Kate Hewitt. Since Reynolds was a Protestant and Hewitt was a Catholic, she kept their engagement a secret, even from her parents. The couple had made a pact before the Civil War. If John were killed while serving in the military, Kate would become a nun.

That first morning at Gettysburg, Reynolds met with Buford and then accompanied some of his soldiers into the fighting at Herbst’s Woods. The troops of the Iron Brigade began arriving and Reynolds was supervising their placement in the line of battle when he suddenly fell from his horse. Command immediately passed to General Abner Doubleday.

Reynolds had died instantly from a head wound. Eight days after attending Reynolds’ funeral, Kate Hewitt applied for admission to the Sisters of Charity Convent in Emmitsburg, Maryland – approximately thirteen miles southwest of Gettysburg.

Battle of Gettysburg: July 2

Around mid-day, as Union troops prepared a major advance from Cemetery Ridge to the Emmitsburg Road, an officer ordered the Sherfys to leave the farm for their own safety. They reunited with their children at a friend’s farm a few miles behind Union lines.

Fighting had shifted south of Gettysburg. Union troops remained on Cemetery Ridge while the Confederates held a long, low crest called Seminary Ridge. The Emmitsburg Road ran parallel to these two positions in a shallow valley, leaving the Sherfy Farm between the two armies.

Peach Orchard

At 1:30 p.m., ignoring orders from army commander General George Meade, General Daniel Sickles advanced his line to the Emmitsburg Road to take advantage of what he deemed to be ground better suited for defense. Sickles’ troops then occupied Sherfy’s now-famous Peach Orchard, one of the highest elevations on the battlefield, but they also formed a salient, which was vulnerable to attack from the south and west.

General Robert E. Lee ordered General James Longstreet‘s newly arrived corps of infantry to attack the Union’s exposed left flank. Confederate plans called for

Around 4:30 p.m. General John Bell Hood launched an assault on Sickles’ thin battleline. Hood’s men swept over Sickles’ troops in Devil’s Den and made their way toward a rocky hill known as Little Round Top. Seeing this movement, the Federals’ chief engineer General Gouverneur K. Warren worked feverishly to rush troops to save Little Round Top for the Union. Two brigades of the V Corps arrived just in time to halt the Rebel advance and secure the Union left.

Barksdale’s Charge

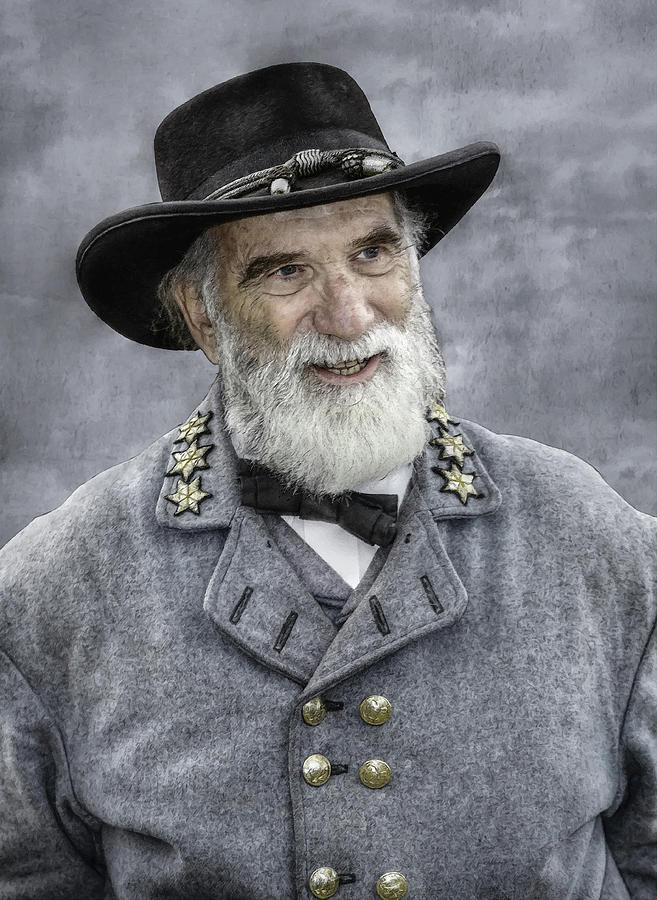

General William Barksdale’s position in the line placed him at the very tip of the salient in the Union left flank anchored at the Peach Orchard. At about 5:30 p.m., Barksdale’s men burst from the woods in an assault that has been described as one of the most awep-inspiring spectacles of the war. A Union colonel was quoted as saying, “It was the grandest charge that was ever made by mortal man.” Although he ordered his subordinate commanders to walk during the charge, Barksdale himself rode on horseback “in front, leading the way, hat off, his wispy hair shining …”

Barksdale’s Mississippi Brigade smashed into the brigade manning the Peach Orchard. Barksdale was wounded in his left knee during the charge, followed by a cannonball injury to his left foot, and finally was hit by a bullet to the chest, knocking him off his horse. He told his aide, “I am killed! Tell my wife and children that I died fighting at my post.” His troops were forced to leave him for dead on the field, and he died the next morning in a Union field hospital at the Joseph Hummelbaugh Farm.

Image: Barksdale’s Charge

Image: Barksdale’s Charge

Sherfy Barn and House in the background

Barksdale at left center holding his hat

By Don Troiani

Prisoner at Sherfy Farm

In the late afternoon of July 2, fierce fighting occurred in the Sherfy Farmyard as Union sharpshooters fired from the house and the cellar. Captain Alanson Nelson of the 57th Pennsylvania had a hair-raising experience at the Sherfy Farm. When a Confederate brigade launched an attack on the house, Nelson realized he was cut off from his unit.

Disdaining the idea of becoming a prisoner of war, Nelson chose flight instead of fight. When he emerged from the house, he saw a group of Confederates in the Sherfy yard not fifty feet away. He later wrote, “I took the chance, and made a dive past them, then firing began.” Nelson concluded that either he moved too quickly or the Confederates were poor shots “for they never touched me.”

The second day’s fighting came to an end; Longstreet’s Corps had failed to take Little Round Top; both sides regrouped for the following day.

Battle of Gettysburg: July 3

On July 3, 1863, the final day of battle, the exhausted armies faced each other across a mile of open farmland. The Confederates had assaulted the Union flanks with little success. Therefore, on this day General Lee planned to attack the Union center in the morning, but General Longstreet’s assault did not begin until 1:00. Confederate batteries used the front yard of the Sherfy property as a staging area during the thunderous two-hour artillery bombardment of the Union center.

During the attack, nine brigades of Confederate soldiers marched more than three-quarters of a mile of open ground susceptible to cannon fire from all directions. Three brigades of General George Pickett‘s division under Generals Richard Garnett, James Kemper and Lewis Armistead led the infantry assault of approximately 15,000 Confederate soldiers against some 6,500 Union troops stationed along Cemetery Ridge.

The Rebels managed to punch a hole in the Union center, but the Army of the Potomac sent them in retreat across the farmland over which they had so gallantly charged. The ill-fated attack left more than 6,000 Confederate casualties. Generals Garnett and Armistead died during the charge, and Kemper was severely wounded.

The Ruins: July 6

Nothing could have prepared the Sherfys for what they saw when Joseph Sherfy and his son Rafael returned to their farm on July 6. The house was battle-scarred, particularly the brick walls on the south and west sides, and shell fragments had made several holes in the roof. A cannon ball had damaged a corner of the house, and another remained lodged in an old cherry tree in the yard. Bloodstains and bullet holes marred the house’s interior. A civilian who visited the battlefield wrote:

The rebels had searched the house thoroughly turning everything in drawers etc. out and clothes, bonnets, towels, linen etc were found tramped in indistinguishable piles from the house out to the barnyard. Four feather beds never used were soaked with blood and bloody clothes and filth of every description was strewn over the house.

Artillery maneuvers had left deep ruts in the ground. Battle trash – guns, haversacks, blankets, bits of clothing, harnesses, broken caissons, canteens, paper, and cartridge shells – littered the grounds. The bodies of horses rotted everywhere, moistened by a heavy rain on July 4 and cooked by the summer heat. Soldiers had pulled up or knocked down most of the trees in the new peach orchard, and damaged the mature trees severely.

During the battle, injured soldiers had sought shelter in the Sherfy Barn, which one officer described as “riddled with shot and shell like a sieve from its base to the roof.” The Confederates later set fire to the barn, and approximately a dozen men were too injured to escape and burned to death inside the structure.

A soldier from the 77th New York Infantry who observed it wrote:

As we passed the scene of conflict on the left was a scene more than unusually hideous. Blackened remains marked the spot where, on the morning of the 3rd, stood a large barn. It had been used as a hospital. It had taken fire from the shells of the hostile batteries, and had quickly burned to the ground. Those of the wounded not able to help themselves were destroyed by the flames, which in a moment spread through the straw and dry material of the building. The crisped and blackened limbs, heads and other portions of bodies lying half consumed among the heaps of ruins and ashes made up one of the most ghastly pictures ever witnessed, even on the field of war.

After the Civil War

Although several neighbors moved west after the battle and started over, the Sherfy family cleaned and restored their home, replanted trees, and rebuilt their property to its previous condition. For many years the Peach Orchard was a popular destination for the men who had fought in its fields, and one wall of the house was reportedly covered with photographs of veterans. A visitor in 1865 wrote that their trees loaded with peaches, and Anna selling them out of a basket.

Image: Otelia Sherfy in Hoops

Image: Otelia Sherfy in Hoops

With sisters Mary and Anna

The Sherfy family’s religion Church of the Brethren cautioned that hoopskirts and other fashionable attire were too worldly for their faith. The decision to allow daughter Otelia to wear hoops for this photograph must have been difficult for Joseph and Mary Sherfy.

The Joseph Sherfy Farm House is a contributing feature to the Gettysburg National Military Park Historic District.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: John Reynolds

Stone Sentinels: Sherfy Farm

American Orchard: The Sherfy Peach Orchard

Otelia’s Hoops: Gettysburg Dunkers and the Civil War – PDF

Civil War Trust: Devil’s Den and Little Round Top, July 2, 1863

“I threw down my gun and held up both my hands,” Prisoners of War, Part I