African American Abolitionist and Women’s Rights Activist

Sojourner Truth was a nationally known feminist and social reformer. During the Civil War, she helped recruit black soldiers for the Union Army. After the war, she tried to secure land grants from the federal government for former slaves, a project she pursued for seven years, meeting with President Ulysses S. Grant to discuss the subject.

Sojourner Truth was a nationally known feminist and social reformer. During the Civil War, she helped recruit black soldiers for the Union Army. After the war, she tried to secure land grants from the federal government for former slaves, a project she pursued for seven years, meeting with President Ulysses S. Grant to discuss the subject.

Image: Sojourner Truth Monument

Florence, Massachusetts

Truth lived in Florence (a village of Northampton) from 1843-1857. She came to Florence to join the Northampton Association of Education and Industry, a utopian community dedicated to equality and justice. After the Association disbanded, she remained in Florence, bought her first home, dictated her autobiography to Olive Gilbert and became a nationally known advocate for women’s rights and the abolition of slavery.

Early Years

She was born Isabella Baumfree in Ulster County in upstate New York in 1797, one of thirteen children. Her family belonged to a wealthy man from Holland. She spoke low Dutch until she was about 10 years old, and always spoke with a Dutch accent. She never learned to read or write.

When she was a teenager, Isabella was sold to a Mr. Dumont, who forced her to marry another slave named Thomas. Together they had five children: Diana, Peter, Hannah, Elizabeth, and Sophia. Dumont sold her son Peter into slavery in Alabama, and Isabella escaped from Dumont with her infant daughter, Sophia. They were taken in by a Quaker family named Van Wagener. With their help, Isabella won a lawsuit, and Peter was returned to her.

In 1828 the state of New York abolished slavery, and Isabella was legally free. In 1829, she moved to New York City, where she worked as a housekeeper and became deeply involved in religion. Her mother had already endowed her with a deep, abiding Christian faith. Soon after being emancipated, Isabella had a vision in which God spoke to her, leading her to develop a “perfect trust in God and prayer.”

In 1843 God told her to travel about the country to tell the truth; Isabella Baumfree became Sojourner Truth. With little more than the clothes on her back, she began walking through Long Island and Connecticut, speaking to people about her life and her relationship with God. She was a very tall woman, with a deep rich voice and a dignified manner, and people began to listen. She believed a woman could do any job as well as a man. Some people wondered if she really was a man dressed in women’s clothing.

After several months of traveling, some friends encouraged her to go to the Northampton Association in Massachusetts, a utopian community dedicated to the betterment of human life. There she met free thinkers like William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick Douglass and David Ruggles. Douglass described her as

“a strange compound of wit and wisdom, of wild enthusiasm and flintlike common sense.”

When the association broke up in 1846, Truth remained in Northampton. With the help of a friend, she moved for the first time into her own home. She dictated her memoirs, and they were published in 1850 as The Narrative of Sojourner Truth: A Northern Slave. She began to speak about abolitionism and women’s rights on the lecture circuit. Over the next decade she traveled and spoke widely. A Quaker gentleman, Henry Willis, invited her to speak in Battle Creek, Michigan, on October 4, 1856. Truth moved to Michigan in 1857 and continued her advocacy activities.

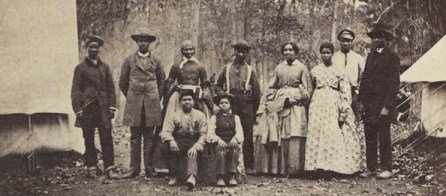

During the Civil War, when President Abraham Lincoln announced the Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863, thousands of slaves from Virginia and Maryland fled to Washington, DC, seeking freedom. The government was unprepared for such an influx, and there was no place for them to live, very little food, and no jobs.

Freedman’s Village was established by the federal government on the grounds of the Custis and Lee estates, what is today Arlington National Cemetery, the Pentagon and the Navy Annex building. The village was a collection of 50 one-and-a-half story houses. Sojourner Truth moved to Washington, DC, and began working with former slaves, who were provided with medical care and training for jobs, such as blacksmithing.

After the Civil War, Sojourner Truth continued to lecture about women’s rights, prison reform, and addressed the Michigan Legislature against capital punishment. She was not afraid to speak her mind. She took women to task for the way they dressed, trussing themselves up in corsets and wearing high heeled shoes and hats trimmed with goose feathers, looking like they were ready to take off and fly like birds.

In 1869 she gave up smoking her clay pipe. A friend asked her how she expected to be admitted to heaven with her smoker’s bad breath. She replied, “When I goes to Heaven I expects to leave my bad breath behind.” This was typical of her witty remarks.

Sojourner Truth died at her home in Battle Creek on November 26, 1883, surrounded by family and friends. It was reported that her funeral service was attended by 1000 people.

In 1886, a friend asked the public for donations to erect a marker at Truth’s grave. The marker deteriorated over time and was replaced several times. An historical marker was put on her grave in 1961 by the Sojourner Truth Association.