Civil War Nurse from New York

Image: Sophronia Bucklin

Image: Sophronia Bucklin

Nurse at Camp Letterman General Hospital

Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

Born in New York State in 1828, Sophronia Bucklin was a seamstress before the war, but put aside her needle and thread to nurse wounded Union soldiers. In her memoirs, In Hospital and Camp: A Woman’s Record of Thrilling Incidents among the Wounded in the Late War (1869), Bucklin recorded her experiences. Eager to do her part for the war effort, Bucklin offered her services as a nurse:

The same patriotism which took the young and brave from workshop and plow, from counting rooms, and college hall… lent also to our hearts its thrilling measure, and sent us out to do and dare for those whose strong arms were to retrieve the honor of our insulted flag. Because we could not don the uniform of the soldier, and follow the beat of the stirring drums, we chose our silent journeys into hospitals and camps, and there waited for the wounded sufferer, who would escape from vital breath, from before the belching flames which burst forth amid lurid clouds of battle.

Beginning in 1862, Sophronia Bucklin worked at hospitals and camps in Virginia, Maryland, Washington, DC and Pennsylvania. She experienced some initial stage fright:

I had been eager to lend myself to the glorious cause of Freedom, and now, on the threshold of the hospital in which gaping wounds, and fevered, thirsty lips awaited me, telling their ghastly tales of the bloody battle, my cheek flushed, and my hand grew hot and trembling. Weak flesh and timid heart would have counseled flight, but a strong will held them in abeyance, and the doors opened to receive me.

Bucklin’s strong will came into play when dealing with doctors, too many of whom, she believed, took out their frustrations and fatigue on nurses. She learned not to back down, and she succeeded in having one doctor dismissed for sexual harassment.

Bucklin at Gettysburg

The great battle ended on Friday, July 3, 1863. Sophronia Bucklin arrived the following day, Saturday, July 4, the first of some forty Union nurses, working for the U.S. Sanitary Commission. She recorded her first impressions of Gettysburg after the battle:

On Saturday we entered the battle town. Everywhere were evidences of mortal combat, everywhere wounded men were lying in the streets on heaps of blood-stained straw, everywhere there was hurry and confusion, while soldiers were groaning and suffering… They lay like trees uprooted by a tornado.

Stripped of cattle and sheep – stores and houses robbed, still the people of Gettysburg stood nobly by their defenders. The women brought forth their contributions of bandages and lint, and poured out with unsparing hand their hidden delicacies, such as wines and jellies, like oil upon the sea of suffering humanity.

One third of the soldiers who marched into Gettysburg did not march out. Many still lay suffering in the hot sun or pouring rain, often unable to reach their canteen or food.

When she asked for directions to the Lutheran Theological Seminary, where a hospital had been established, Bucklin was told that she was not needed there. The patients from the hospital at the Seminary were soon to be brought out to the field. Bucklin worked in this environment for the first two weeks.

Caring for the Wounded

The first mention of establishing a general hospital at Gettysburg was contained in a circular from the Headquarters of the Army of Potomac dated July 5, 1863. The focus of the circular dealt with troop movements and accompanying supplies for the pursuit of General Robert E. Lee‘s retreating forces; however, care of the wounded was systematically covered in general terms.

Assistant Adjutant-General Seth Williams indicated, “The medical director will establish a general hospital at Gettysburg for the wounded that cannot be moved with the army.” Jonathan Letterman, medical director for the Union Army of the Potomac, appointed members of his command to comply with the circular.

Field Hospitals

Dr. Henry Janes, surgeon for U.S. Volunteers, was left in charge of the various field hospitals at Gettysburg. Most of the these hospitals were in churches, schools, private homes and at the farms scattered over the surrounding countryside of Gettysburg.

Janes and his staff faced a daunting challenge as they began moving the wounded from the field hospitals. Union field hospitals were clustered south and southeast of the town, generally between the Hanover and Taneytown roads. Confederate field hospitals were spread out – northeast, north, west and southwest of Gettysburg.

The wounded at the field hospitals in Janes’ charge totaled 20,995: 14,193 Union and 6,802 Confederate. If the soldiers had recovered sufficiently enough to travel, they were moved to the railroad depot and then transported home or to more permanent military hospitals in large cities in the east.

Camp Letterman General Hospital

The new hospital, named after medical director Jonathan Letterman, was situated east of Gettysburg along the York Pike, on elevated ground that was part of the George Wolf farm. A large stand of trees, provided fresh air, cooling breezes and shade. The railroad was nearby, which facilitated the movement of the wounded to the railroad cars. A natural spring provided a good supply of clean, fresh water.

The hospital included a cook house, dining tents, operating tents, tent quarters for support staff and surgeons, quarters and tent stations for the U.S. Sanitary Commission and U.S. Christian Commission, the dead house, embalming tent and hospital graveyard. It soon became a model of a clean, efficient and well-managed medical care facility.

The new hospital consisted of more than four hundred hospital tents placed in rows about ten feet apart. A tent held up to ten patients. When the weather cooled in the fall, each tent was heated by a Sibley stove. Each medical officer was assigned to care for forty to seventy patients.

After Dr. Henry Janes consolidated the patients from the field hospitals and sent those who were sufficiently recovered on the cars, he had approximately four thousand-two hundred soldiers who were too ill to travel. They were moved to Camp Letterman beginning on July 20, 1863.

A line of stretchers, a mile and a half in length, each bearing a hero, who had fought nigh to death, told us where lay our work, and we commenced it at once. I washed agonized faces, combed out matted hair, bandaged slight wounds, and administered drinks of raspberry vinegar and lemon syrup, while Mrs. Caldwell wrote letters to those who were waiting in dread suspense for news of their soldier, little knowing that he lay stretched on a narrow bed, weak with loss of blood…

She was not exactly thrilled about caring for Confederate soldiers:

More than half the wounded men in the hospital were rebel soldiers, grim, gaunt, ragged men – long-haired, hollow-eyed and sallow-cheeked… It was universally shown here, as elsewhere, that these bore their sufferings with far less fortitude than our brave soldiers who had been taught, in sober quiet homes in the North, that while consciousness remained, their manliness should suppress every groan, and that tears were for woman and babes.

Bucklin was thankful that the Sanitary Commission had brought food and hospital supplies because the Union medical supplies were stuck in a very long line of wagons:

…for Government stores could not be obtained, and in view of the host of wounded, the ordinary hospital supplies were as a drop of water in the depths of the cool, silent well… In this open field, our supplies were [soon] landed from Washington. Whole car loads of bread were moulded through and through, while for a time we were sorely pinched for the necessaries of life.

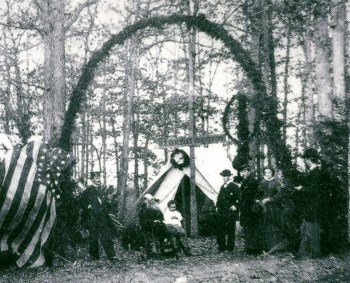

Image: U.S. Sanitary Commission Tent

Image: U.S. Sanitary Commission Tent

Camp Letterman, Gettysburg

Child on lap of old man in front of tent

Woman stands in cluster of people on right

By August 7, 1863 all of the corps and field hospitals had been closed, and only Camp Letterman remained in operation, with more than three thousand patients at that time. Union and Confederate wounded were both treated at the camp by army doctors and personnel of the United States Christian Commission and the United States Sanitary Commission, but many died from their wounds or infection.

Sophronia Bucklin was an efficient and dedicated nurse, and a compassionate friend to her patients. As the days passed, her heart softened toward the Confederates:

With the same care from attendants, and the same surgical skill, many more of the rebels died than of our own men – whether from the nature of their wounds, which seemed generally more frightful, or because they lacked courage to bear up under them, or whether the wild irregular lives which they had been leading had rendered the system less able to resist pain, will always remain a mystery with me… Notwithstanding their hostility to us Northerners, I had much respect for them…

By the end of August 1863, the patient population had dropped to 1,600 and fell to 300 by late October, with only 100 on November 10, 1863. Union medical officers closed Camp Letterman November 20, 1863, the day after President Abraham Lincoln dedicated the Soldiers’ Cemetery with one of the best known speeches of all time, the Gettysburg Address.

Nurse Bucklin recalled that:

…[as] the hospital tents were removed – each bare and dust-trampled space marking where corpses had lain after death-agony was passed, and where the wounded had groaned in pain. Tears filled my eyes when I looked on that great field, so checkered with the ditches that had drained it dry. So many of them I had seen depart to the silent land…

When the war ended, Bucklin returned to New York State and resumed work as a seamstress. She was a proud member of a national organization that honored her sisters in war, the Woman’s Relief Corps of the Grand Army of the Republic. She never married.

What she saw at Gettysburg, Sophronia Bucklin would never forget. Nor would she forget the soldiers who died there. In 1869, she published an account of her experiences entitled In Hospital and Camp: A Woman’s Record of Thrilling Incidents Among the Wounded in the Late War. She died in 1902, at age 74.

SOURCES

Civil War Journal: Camp Letterman

Sophronia Bucklin Nurses the Wounded at Gettysburg

Sophronia E. Bucklin: Sanitary Commission Nurse at Gettysburg