Sharpsburg Resident During the Battle of Antietam

Teresa Kretzer is remembered for hanging a huge American flag over Main Street during the Civil War, much to the chagrin of her Secessionist neighbors. When the Southern army arrived she saved the flag she and her neighbors had made by hiding it in the ash heap behind the family smokehouse.

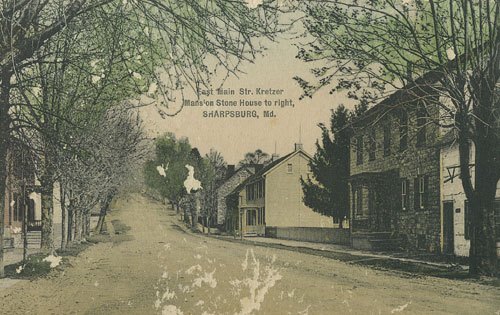

Image: Main Street in Sharpsburg, Maryland in 1862

At the time of the Civil War, Sharpsburg was a rural village with rutted dirt roads; a place where many people kept cows and chickens in their back lots and tended big gardens. In September 1862, fighting from the Battle of Antietam (also known as the Battle of Sharpsburg) spilled into the town’s streets.

In the days leading up to the Battle of Antietam in September 1862, Confederate General Robert E. Lee [link] concentrated his invading army outside Sharpsburg, Maryland. Victorious at the Second Battle of Bull Run in August, Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia hoped to garner new recruits and supplies in Maryland, a slave-holding state that had remained in the Union. However, Union General George B. McClellan closely pursued his rival.

Clifton Johnson interviewed Sharpsburg-area residents about their Civil War experiences in 1913, including Teresa Kretzer, and published them in his book Battlefield Adventures (1915). The excerpts below are from that source:.

Sunday, September 14

We were all up in the Lutheran Church at Sunday school on the Sunday before the battle [September 14] when the Rebel cavalry came dashing through the town. … they nearly worried us to death asking for something to eat. They were half famished and they looked like tramps – filthy and ragged. I was twenty years old then. My father was a blacksmith, and we lived in this same big stone house on the main street of the town. …

Image: Lutheran Church in Sharpsburg

This church illustrates the extent of the Union offensive during the Battle of Antietam.Most of us in this region favored the Union, and the ladies had made a big flag out of material that the townspeople bought. For a while we had it on a pole in the square, but some of the Democratic boys cut the flag rope every night. So we took the flag down and hung it on a rope stretched across from our garret window to that of the house opposite. When we heard that Lee had crossed the Potomac … a lady friend of mine and I put it in a strong wooden box, and buried it in the ash pile behind the smokehouse.

Tuesday, September 16

Although an immediate Union attack on the morning of September 16 would have had an overwhelming advantage in numbers, McClellan’s trademark caution and his belief that Lee had as many as 100,000 men at Sharpsburg caused him to delay his attack for a day. This gave the Confederates more time to prepare defensive positions and allowed General James Longstreet‘s corps to arrive from Hagerstown and General Stonewall Jackson‘s corps to arrive from Harpers Ferry. Jackson defended the left (northern) flank, anchored on the Potomac, Longstreet the right (southern) flank, anchored on the Antietam, a line that was about 4 miles long.

By Tuesday there was enough going on to let us know we were likely to have a battle nearby. Early in the day two or three Rebels, who’d been informed by some one that a Union flag was concealed at my father’s place, came right to the house, and I met ’em at the door. Their leader said: “We’ve come to demand that flag you’ve got here. Give it up at once or we’ll search the house.” “I’ll not give it up, and I guess you’ll not come any farther than you are, sir,” I said.

They were impudent fellows, and he responded, “If you don’t tell me where that flag is I’ll draw my revolver on you.” “It’s of no use for you to threaten,” I said. “Rather than have you touch a fold of that starry flag I laid it in ashes.” They seemed to be satisfied then and went away without suspecting just how I’d laid it in ashes.

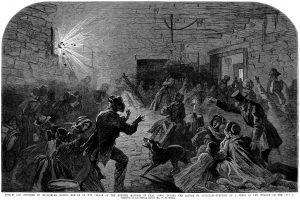

Tuesday afternoon the neighbors began to come in here. Our basement was very large with thick stone walls, and they wanted to take refuge in it if there was danger. There were women and children of all ages and some very old men. Mostly they stood roundabout in the yard listening and looking. The cannonading started late in the day, and when there was a very loud report they scampered to the cellar.

Their neighbors remained in the Kretzer’s cellar until about 10 o’clock the following evening mostly without food. Some of the women brought food for their children. With shells flying hither and yon, no one ventured up to the Kretzer kitchen to cook. Luckily, a spring in the cellar provided clean drinking water.

Leslie’s Illustrated Magazine

Wednesday, September 17

At dawn, General Joseph Hooker‘s corps mounted an assault on Lee’s left flank. Attacks and counter-attacks swept across David Miller’s Cornfield and around the Dunker Church. At the Sunken Road, repeated Union assaults eventually pierced the Confederate center, but the Federal advantage was not continued.

In the afternoon, Union General Ambrose Burnside‘s corps entered the action, capturing a stone bridge over Antietam Creek (which would soon be named Burnside’s Bridge in his honor). Burnside planned to maneuver around the Confederate right flank, converge on Sharpsburg and cut Lee’s army off from Boteler’s Ford, their only escape route across the Potomac.

At 3 p.m. Burnside began an advance against the Confederate right with more than 8,000 troops and twenty-two guns for support. An initial assault against the Confederate right pushed them back past Cemetery Hill and to within 200 yards of Sharpsburg, where retreating Confederates caused a panic in the streets.

At a crucial moment in Burnside’s endeavors, Confederate General A.P. Hill‘s division arrived from Harpers Ferry around 3:30 p.m. At 3:40 p.m. General Maxcy Gregg’s South Carolinians attacked the 16th Connecticut in the cornfield of farmer John Otto; their line quickly disintegrated. The 4th Rhode Island came up to help, but they had poor visibility amid the high corn stalks; they were also disoriented because many of the Confederates were wearing Union uniforms they had captured at Harpers Ferry. The Rhode Islanders also retreated, leaving the 8th Connecticut isolated. They were enveloped and driven down the hills toward Antietam Creek.

The IX Corps had suffered casualties of about 20% but still possessed twice the number of the Confederates confronting them. Unnerved by the collapse of his flank, Burnside ordered his men all the way back to the west bank of Antietam Creek, where he urgently requested more men and guns. McClellan was able to provide just one battery. He said, “I can do nothing more. I have no infantry.”

That was a blatant lie. McClellan had two fresh infantry corps in reserve, General Fitz John Porter‘s V Corps with 10,300 infantrymen and General William Franklin’s VI Corps with 12,000 soldiers. However, McClellan, as always, was too cautious, fearing that he was greatly outnumbered and that General Lee might mount a massive counterattack at any moment. Burnside’s men spent the rest of the day guarding the bridge they had suffered so much to capture.

General A.P. Hill’s surprise counter-attack had driven Burnside’s force back and effectively ended the battle. Although outnumbered two-to-one, Lee had committed his entire force, while McClellan sent in less than three-quarters of his army, enabling Lee to fight the Union Army to a standstill.

Teresa Kretzer, September 17

We had two cows and a horse in our stable, and at dinner time [noon] Mother and I went to feed ’em. We climbed up to pull down some hay and found the haymow just full of Rebels a-layin’ there hiding. “Madam, don’t be frightened,” one of ’em said to Mother. “We’re hidin’ till the battle is over. We’re tired of fightin’. We were pressed into service, and we’re goin’ to give ourselves up as soon as the Yankees get here.” And that was what they did. When the Yankees rushed into town these Rebels came through the garden and gave themselves up as prisoners.”

In the evening mother and I slipped down to the stable and did the milking. But afterward we went back to the cellar, for the firing kept up till ten o’clock. Then we came up and snatched what little bit we could to eat. … About midnight we heard the Rebels retreating.

We were overjoyed to know that our men had won – yes, we certainly were happy. Well, the next morning everything was quiet. It was an unearthly quiet after all the uproar of the battle. The people who had taken refuge with us saw that the danger was over, and they scattered away to their homes. Father and I went out on the front pavement. We could see only a few citizens moving about, but pretty soon a Federal officer came cautiously around the corner by the church. He asked Father if any one was hurt in the town and said they had tried to avoid shelling it, and he was awful sorry they couldn’t help dropping an occasional shell among the houses. …

I lost no time now in getting our flag from the ash heap so I could have it where it would be seen when our men marched into the town. I draped it on the front of the house, but I declare to goodness! I had to take that flag down. It made the officers think our house was a hotel, and they’d ride up, throw their reins to their orderlies, and come clanking up the steps with their swords and want something to eat. So I hurried to get it swung across the street, and after that, as the officers and men passed under it they all took off their hats. Their reverence for the flag was beautiful, and so was the flag. …

The trains soon arrived with the hardtack, and there were baggage wagons and ambulances and everything. We had our men here with us quite a while camped in the town woods, and so constant was the coming and going of troops and army conveyances on the highways that we didn’t get to speak to our neighbors across the street for weeks. Those were exciting times, but we felt safe. Of course there were some common, rough fellows among the soldiers, but as a general thing we found them very nice and we became much attached to them. When they went away it left us decidedly lonely here.

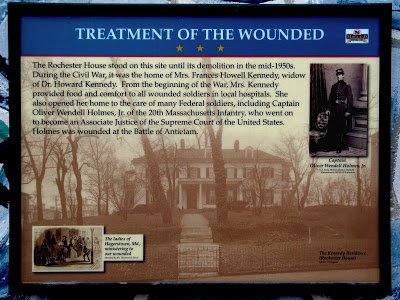

The toll of the Battle of Antietam was horrendous – approximately 22,000 men were dead, wounded, or missing: the highest single-day casualty rate of the Civil War. Homes, barns and other structures for miles around were turned into hospitals, and the diseases carried by the soldiers took a heavy toll on the civilians in and around Sharpsburg.

Historian Stephen Sears wrote:

Of all the days on all the fields where American soldiers have fought, the most terrible by almost any measure was September 17, 1862. The battle waged on that date, close by Antietam Creek at Sharpsburg in western Maryland, took a human toll never exceeded on any other single day in the nation’s history. So intense and sustained was the violence, a man recalled, that for a moment in his mind’s eye the very landscape around him turned red.

In 1932, Theresa Kretzer died at the age of 88 and was buried in Sharpsburg’s Mountain View Cemetery.

SOURCES

History of Sharpsburg

Wikipedia: Battle of Antietam

World History Project: Battle of Antietam

The Bloodiest Day – September 17, 1862

Sites and Stories Blog: Bravest Girl in Sharpsburg

Thank you for the info provided. I have a sketch of burnside bridge with a signature of Ketzer. Would you know who the artist was? First name of course. It seems quite old.