Heroism and Sacrifice at Trostle Farm

In July 1863, the Trostle Farm south of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania was owned by Peter Trostle, but it was occupied by his daughter-in-law Catherine and her nine children. Her husband Abraham was incarcerated in the lunatic asylum. The Annual Report of the Board of Commissioners stated that: “Abraham Trostle has been confined and chained to his room for five years.”

In July 1863, the Trostle Farm south of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania was owned by Peter Trostle, but it was occupied by his daughter-in-law Catherine and her nine children. Her husband Abraham was incarcerated in the lunatic asylum. The Annual Report of the Board of Commissioners stated that: “Abraham Trostle has been confined and chained to his room for five years.”

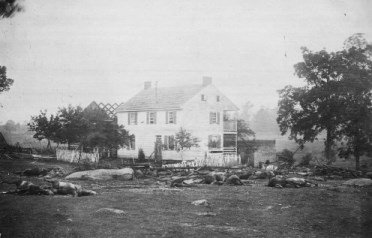

Image: Dead horses at Trostle Farm

This photo of the Catherine Trostle house was taken on July 6, four days after the fighting raged around her farm.

The 134 acre farm was described as having: a newly built wood-frame house, a spring house, a large Pennsylvania style bank barn, a wagon shed addition, a corn crib and an apple orchard. Adjacent to the buildings was a narrow lane that ran east to west. The farmhouse and the barn were likely used as field hospitals.

Trostle owned most of the land bordered by Plum Run to the east, Emmitsburg Road to the west, and Wheatfield Road to the south. In the summer of 1863, Abraham Trostle was busy dismantling an earlier log house and building a large brick summer kitchen. The orchard near the house and the rich fields yielded enough apples, corn, wheat and rye to support the family quite well. On July 2 the Trostles were abruptly forced from their home when the fighting broke out nearby.

9th Massachusetts Artillery Battery

The 9th Massachusetts Battery was organized in the summer of 1862, and left Boston for Washington, DC on September 3, 1862. The unit spent the fall and winter of 1862-1863 in various positions on the outskirts of Arlington, Virginia, where they were drilled extensively in field artillery tactics. In April 1863, they marched to Centreville, Virginia, where they remained until the Gettysburg Campaign.

Their commander was 22 year-old Captain John Bigelow of Brighton, Massachusetts. On June 15, still encamped at Centreville, the men of the 9th Massachusetts were swept up with the Army of the Potomac as they headed northward. The men of the 9th were new to marching and it was difficult going.

By June 30, 1863, the 9th Massachusetts Battery was in Taneytown, Maryland, about 14 miles from Gettysburg. They camped there until the morning of July 2, reaching Gettysburg about mid-day on July 2. As part of the III Corps Artillery Reserve, the 9th was placed behind the lines near the George Spangler Farm [link], ready to be called when needed. There they watered their horses, ate and rested for a few hours.

Around 4pm, as General James Longstreet‘s Confederates began to assault the Union III Corps, a message came from the commander of the III Corps artillery brigade, requesting two batteries to come to his aid near the Peach Orchard. The men of the 9th were soon moving along a lane past the Trostle Farm, through a gate, and across a field toward the Wheatfield Road.

Though Bigelow had prior combat experience at Malvern Hill (near Richmond) and Fredericksburg the previous year, this would be the first time the men of the 9th Massachusetts Battery had taken part in a battle. As they approached their destination, there was heavy fighting all around them, and the sights and sounds were unnerving to many of the novice artillerymen.

Captain Bigelow later described the scene:

A spirited military spectacle lay before us; General Daniel Sickles was standing beneath a tree close by, staff officers and orderlies coming an going in all directions; at the famous Peach Orchard angle on rising ground along the Emmitsburg Road, about 500 yards in our front, white smoke was curling up from… the deep-toned booming of [Union] guns… while the enemy’s shells were flying over or breaking around us.

Danger on Wheatfield Road

The 9th Massachusetts deployed under Confederate artillery fire along the Wheatfield Road, facing southward about halfway between the Peach Orchard and the Wheatfield. They took into battle 110 men, 6 twelve-pound Napoleons and 88 horses. Bigelow directed their missiles at the enemy’s batteries posted along the Emmitsburg Road, and they soon slowed their fire. When several units of rebel infantry were seen forming less than half a mile to the south, the 9th turned their guns and began shelling the Rose Farm and Woods.

Meanwhile the 9th was left exposed to the withering fire of CSA General Joseph Kershaw, who had sent two of his Southern regiments against Bigelow’s front and left, and William Barksdale’s Mississippians were soon coming in on the right. Bigelow’s men did not have time to limber up their guns, so they pulled them to the rear with might and muscle as they retreated northward – loading, firing and pulling the guns as they went.

Captain Bigelow noticed a new threat coming toward them:

Glancing toward the Peach Orchard on my right, I saw that the Confederates [Barksdale’s brigrade] had come through and were forming a line 200 yards distant, extending back, parallel with the Emmitsburg Road, as far as I could see… [His superior] Colonel McGilvery rode up at this time, and told me that [all of Sickle’s] men had withdrawn and I was alone on the field, with no supports… limber up and get out.

Bigelow quickly realized that if he carried out that order without infantry support:

Every saddle would have been emptied in trying to limber up… No friendly supports of any kind were in sight; but Johnnie Rebs in great numbers. Bullets were coming into our midst from many directions and a Confederate battery added to our difficulties…

So they continued, with the men dragging some of the heavy guns across the pastureland south of the Trostle house and barn. As man and beast struggled with their heavy loads, gunners rammed charges down the muzzles as they ran, stopping briefly to fire the guns toward the oncoming rebels. As they reached the Trostle farmyard, they had just enough time to limber up the guns and start toward the rear at a gallop.

John Bigelow’s 9th Massachusetts Battery holding off William Barksdale’s Confederates at the Trostle Farm Gettysburg, July 2, 1863

Just then, Lt. Colonel Freeman McGilvery rode toward them, telling Bigelow that he had discovered a 1500-yard gap in the Union line along the southern end of Cemetery Ridge. McGilvery intended to patch the broken line with reserve artillery batteries (the infantry had retreated), but he needed time to deploy them, and the 9th Massachusetts was in a perfect position to buy him that time:

Captain Bigelow, there is not an infantryman back of you along the whole line from which Sickles moved out. You must remain where you are and hold your position at all hazards, and sacrifice your battery if need be, until at least I can find some batteries to put in position and cover you. The enemy are coming down on you now.

To Bigelow the task seemed impossible. The exhausted battery was trapped in the angle of two stone walls, making retreat impossible. Bigelow later recalled, “I was very cramped for room and my ammunition was greatly reduced.” Yet the men of the 9th Massachusetts did not hesitate when he ordered them to prepare for action. Bigelow hurriedly posted his guns and ordered all of the remaining ammunition to be piled by each piece for rapid firing.

With the six field pieces loaded and arranged in a semi-circle and horses and limbers pushed into the angle of the stone walls, they were ready not a moment too soon. The Confederates were closing rapidly. Bigelow recalled the harrowing experience:

Waiting till they were breast high, my battery was discharged at them, every gun loaded with double canister and solid shot, after which through the smoke [we] caught a glimpse of the enemy, they were torn and broken, but still advancing. The enemy opened a fearful musketry fire, men and horses were falling like hail… Sergeant after sergeant was struck down, horses were plunging and laying about all around…

The 9th was overrun, melded into the Southern ranks as if they had not been a separate body only moments earlier. Desperate hand-to-hand fighting ensued. Some of the men used artillery rammers and sponge rods as weapons. To keep the cannons from being pulled out, the rebels began shooting the horses, still strapped to their harnesses. A few men fought their way through the throng and pulled two guns to the rear, leaving four in the hands of the enemy.

When the men of the 9th ran out of canister, they began using shell with the fuses cut short so they would burst at close range. Directing the battle from horseback, Bigelow witnessed:

The enemy crowded to the very muzzles [of the guns] but were blown away by the canister. Notwithstanding their insane, reckless efforts, not an enemy came into the battery from its front. The rapid fire recoiled the guns into the corner of the stone wall, which more and more cramped my position.

Canister ammunition began to run low, and Bigelow ordered case shot with the fuses cut short so they would explode in the enemy’s faces. Knowing the end was near, Bigelow ordered his crews to prepare for a retreat and then rode to the stone wall, hoping to make a better opening through which the remaining batteries could escape.

Just then Kershaw’s skirmishers came running down the wall. The battery’s bugler, Charles Reed, called out a warning to his captain. Bigelow could not hear the warning above the melee. Six skirmishers fired directly at him; he was shot twice, still in the saddle. The injured commander gave the order to retreat:

The men abandoned the death trap and made their way to the rear, leaving behind the shattered remains of the battery and a sacrifice of three of four officers, six of eight sergeants, 19 enlisted men, 88 horses and four of their six guns.

Bigelow’s horse had also taken two bullets; as it staggered, the captain slowly slid out of the saddle and fell near the wall. Charles Reed came forward and offered his help, but he was told to save himself. With deadly missiles still flying, the bugler disobeyed orders and helped the captain to the rear, narrowly escaping being taken prisoner. Bigelow survived his wounds; Reed earned a Medal of Honor for his heroic actions.

The 9th Massachusetts Battery had fought until it seemed useless to continue. They had given McGilvery approximately 30 minutes, enough time for him to get his artillery into place. The Confederates took one more of the Union batteries, but soon retreated. McGilvery’s patched-together line of fieldpieces from various commands filled the gap in the Union line, and was instrumental in halting the final Confederate advance toward the Union center on July 2, 1863.

The following day, the remains of the 9th Massachusetts Battery were posted in Ziegler’s Grove at the base of Cemetery Hill. Lieutenant Richard Milton, the only officer still standing, was now in command. With only two guns, the battery was lightly engaged during Pickett’s Charge.

The Aftermath

When the Trostle family returned to their home, they were unprepared for the carnage that greeted them. The house was wrecked, crops and fences gone, household articles and farm utensils broken. Both the house and barn sustained shell damage. Captain Willard Smith noted in a dispatch to Washington that prisoners had buried 30 Confederates and more than 100 horses with the assistance of citizens, the horses being among the last of the dead to be enterred.

Image: The Trostle Barn

Image: The Trostle Barn

Catherine Trostle submitted a claim to the federal government for damages totalling $3188, a huge sum in those days. She also noted that 16 dead horses were left by the door of the house and probably 100 lay around the farm.

This is an excerpt from that claim:

27 acres wheat destroyed $600.00

9 acres Corn $360.00

8 acres Oats $80.00

4 acres Barley $50.00

1 acre Potatoes $50.00

32 acres Grass $650.00

20 tons of Hay out of the barn $300.00

The Compensation Law of July 4, 1864 provided reimbursement only for civilian property damaged or destroyed by Union forces, not those victimized by Confederates or as a result of battle. Therefore “the losses sustained by the claimant in this case are in the nature of damages and are, therefore, not entitled to consideration.”

In January of 1899, the Trostle heirs sold the farm to the National Park Service for $4500.

SOURCES

9th Massachusetts Artillery Battery

9th Massachusetts Battery at Gettysburg

Stone Sentinels: The Trostle Farm on the Gettysburg Battlefield

NPS.gov: Unsung Heroes of Gettysburg: We Saved the Line from Being Broken