Women at the U.S. Treasury Department

Image: Lady Clerks Leaving the Treasury Department at Washington

This illustration was published February 18, 1865, in Harper’s Weekly.

During the Civil War, the Department of the Treasury in Washington, DC hired women workers to fill clerical positions vacated by men who had left to fight with the Union Army. Until that time, clerking was strictly a male occupation. Believing women were particularly well-suited for the task, the Treasurer of the United States assigned them to hand-cut paper money, usually printed in amounts of four bills per sheet.

Backstory

Prior to 1790, the ground now covered by magnificent public and private buildings and known as the City of Washington, was part of a Maryland plantation. That year, at the request of President George Washington Congress passed an act creating the District of Columbia, an area of 100 square miles in Maryland and Virginia. The Virginia portion included the city of Alexandria, which was ceded back to that State in 1846, and the District now occupies about sixty-five square miles.

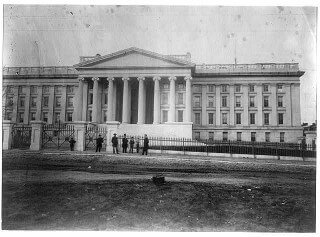

Treasury Building

The Treasury Department has been located next to the White House since the federal government moved from Philadelphia to Washington, DC in 1800. However, the first two Treasury buildings burned to the ground, and at the time of the Civil War, the new one was still uncompleted. On a trip to the United States, British novelist Anthony Trollope described the building:

These public offices stand with their side to the street, and the whole length is ornamented with an exterior row of Ionic columns raised high above the footway. This is perhaps the prettiest thing in the city, and when the front to the north has been completed, the effect will be still better. The granite monoliths which have been used, and which are to be used, in this building are very massive.

Civil War

In the early days, when its spaces were still being designed and built, men were the only employees of the Treasury Department. With the outbreak of the war in 1861, male treasury clerks were formed into a militia unit and the building was prepared to be the last bastion of the Union government in the District. It served as a fortification against any potential Confederate attack. The nation’s finances were also protected. More importantly, the financial requirements of the war required an expansion of the Department’s responsibilities.

Image: South entrance to the Treasury building in Washington, DC during the war

Image: South entrance to the Treasury building in Washington, DC during the war

Treasurer of the United States

During the Civil War, Francis Spinner served as Treasurer of the United States (1861-1875), an official in the Department of the Treasury who was charged with the receipt and custody of government funds. Many of his employees resigned to join the Union Army – just as a revolution in the country’s money system began: To help finance the Civil War, the government was printing greenbacks for the first time. The new notes had to be cut and counted, and Spinner clamored for more clerks. In an article for The Home Magazine Treasurer Spinner wrote:

When I became Treasurer of the United States, I hunted around for a chance to carry out what were called my peculiar ideas in regard to women. It was not long before an opportunity presented itself. When a banker, I had found that my wife and daughters could trim bank-notes faster and more neatly than my clerks or I could, so I used to let them do that work for me… I went to [Salmon P. Chase], then Secretary of the Treasury… and said to him that these young men should have muskets instead of shears placed in their hands, and be sent to the front, and their places be filled by women, who would do more and better work.

At first, the women did use scissors to cut the long sheets of money. Machines were later introduced to do the cutting, and female clerks were assigned to count the currency. In this position, the women worked alongside the men, but they were paid an annual salary of $600, half that of the lowest-paid male clerk.

Most sources state that women first worked for the federal government in the 1860s, but that is false. According to The Numismatist magazine of May 2010 and Treasury Department archives, “two females [were] hired in early 1795 at the fledgling Philadelphia Mint.” Many women were working at the United States Mint in San Francisco by the 1850s, where they produced gold and silver coins. In the Adjusting Room, they carefully weighed the circular blanks, called planchets, and prepared them to be stamped into coins. They rejected those that did not meet the weight requirement and filed down those that were too heavy.

Government Girls

Within the Treasury Department, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing prints currency and postage stamps for the federal government. In April 1862, the Bureau hired its first female employee, Miss Jennie Douglas, to cut and trim the new greenback currency and prepare it for circulation. She performed her duties quickly and skillfully. Within a few months, she had earned a reputation as the Bureau’s best and most proficient note-cutter, proving that women were well-suited for work previously done by men only.

Image: Women working in the bronzing or sealing room at the Treasury Department

Image: Women working in the bronzing or sealing room at the Treasury Department

In a matter of weeks, the Bureau hired seventy more women as currency cutters. They worked a 10- to 12-hour day and were paid about $600 a year, about one-third the wages earned by men doing the same job. Droves of widows or mothers of men wounded or killed in the Civil War were employed at the Treasury Department in Washington, DC. To get the jobs, however, the women needed connections. Many secured their positions by personally appealing to President Abraham Lincoln. It is said that he never refused such a request; he simply tore a strip from a piece of paper and penned: “Give this lady employment. Abraham Lincoln.”

Grace Bedell was a girl from New York who had written to Lincoln in 1860 urging him to grow a beard, which he did. After her father had lost most of his property, Bedell contacted the president again four years later. In 2007, a letter was discovered by the Lincoln Archives Digital Project in 2007, in which Bedell wrote: “I have heard that a large number of girls are employed constantly and with good wages at Washington cutting Treasury notes and other things pertaining to that department. Could I not obtain a situation there?” It is not known whether or not Bedell worked at the Treasury.

In her book, Women in the Civil War (1966), Mary Elizabeth Massey wrote that “the ‘government girls’ were to become a permanent part of the Washington scene.” Union officer William Doster wrote in his diary:

A notable feature on the streets of the capital is the female Government employees; especially the Treasury girls. They are generally young and of good families – for it takes some influence to get into a department. There are many black sheep among them, however. They get $600 a year which is little when board is hard to get at $30 per month, and an ordinary room costs $20 per month.

Construction on the Treasury Department building continued during the Civil War. Journalist Noah Brooks wrote in 1863:

Work on the Treasury extension is going on rapidly, and already one or two bureaus have been moved into their new quarters. The old system of many small rooms has been abolished, and each department or bureau is put in one great room by itself, well provided for light, ventilation, and comfort, and the whole being under the immediate supervision of the chief clerk or controller of the bureau. The private rooms and office of the Secretary of the Treasury are truly palatial in style and finish. The walls are richly decorated in gold and colors, the passages paved with tessellated marble and the floors are to be covered with rich carpets of appropriate design.

As the War continued over four years, more women were hired to assist in the production of currency and various clerical positions. At the time, male clerks had a salary of $1,200 annually while women were paid $900 a year for doing the same work. Nevertheless, women became a significant segment of the workforce at the Treasury due to the initiatives undertaken by Treasurer Francis Spinner, who served from 1861-1875 across the terms of Presidents Abraham Lincoln, Andrew Johnson and Ulysses S. Grant.

Construction of the west wing of the Treasury building was finally completed in 1864. The 1864 Stranger’s Guide-book to Washington City reported:

This is a noble structure, and is situated on Fifteenth street, just south of the State Department. Pennsylvania avenue is here cut off, but continues again above the State Department, and thence runs west to Georgetown. The Treasury building is of granite; over 460 feet in length and 266 feet wide. The east front has colonnade of Ionic columns, 300 feet long. These columns are 42 in number. Projecting porticos decorate the north and south ends of the building. A more imposing structure than this cannot be found in the city. The granite of which it is constructed is from Dix Island, on the coast of Maine. Prior to 1855 the building occupied by the Treasury Department was 336 feet long, with a depth at the centre of 190 feet, but at that time projections, which gives it its present length, were added. There is also a portico about the centre of the east front. The building is not yet fully completed according to the plan of the architect, but workmen are continually employed upon it.

Continuing through the last half of the 19th century, increasing numbers of women were employed at the United States Treasury Department. Treasurer Spinner was one of the first senior government officials to realize that the wartime problems of increasing workload and labor shortages could easily be solved by hiring women

In 1909, Treasurer of the United States Francis Spinner, who first employed women in the Treasury Department, was memorialized with a statue erected in his honor in his hometown of Herkimer, New York. The monument was a gift from the women employees who worked under Spinner. His famous signature adorns the pedestal as it did the Civil War greenbacks. Inscribed in the base of the pedestal is a quote by Skinner: “The fact that I was instrumental in introducing women to employment in the government gives me more satisfaction than all the other deeds of my life.”

In 1909, Treasurer of the United States Francis Spinner, who first employed women in the Treasury Department, was memorialized with a statue erected in his honor in his hometown of Herkimer, New York. The monument was a gift from the women employees who worked under Spinner. His famous signature adorns the pedestal as it did the Civil War greenbacks. Inscribed in the base of the pedestal is a quote by Skinner: “The fact that I was instrumental in introducing women to employment in the government gives me more satisfaction than all the other deeds of my life.”

Image: Monument to U.S. Treasurer Francis Spinner

First official in the Treasury Department to hire women

Showing his signature on the Civil War greenbacks

By sculptor Henry J. Ellicott

Confederate Treasury Girls

Excerpt from the book The World of the Civil War: A Daily Life Encyclopedia:

The Treasury Department of the Confederate States of America was also the earliest and largest employer of women. Female treasury workers, popularly called Treasury girls, earned high wages for signing and cutting Confederate currency. The job required excellent penmanship, which was usually acquired by educated, upper-class women. Many of the women who became treasury girls had never worked outside of the home. As husbands, brothers, and fathers left for the front, upper-class women who had relied on male family members for income were forced to work for pay.

Women fought hard to secure these positions because they were among the highest-paid in the Confederacy. Although they were paid only half the salary of male clerks, they still made $65 a month. At the time, Confederate privates earned only $11 a month, female workers at the Georgia Soldiers Clothing Bureau were paid between $24 and $48 a month, and female arsenal workers only made about $30 a month. Treasury girls worked from 9:00 a.m. until 3:00 p.m. for five days a week, which meant that they worked less than male clerks in comparable positions.

Treasury girls worked as either note clippers or signers. Note clippers trimmed the Confederate bills while signers carefully signed each note. Supervisors expected workers to complete more than 3,000 bills a day without any errors; they were docked 10 cents for every damaged bill, imperfect signature, or blotted spot of ink. Accounts from the girls indicate that some of them worked to maintain their lifestyles rather than to avoid starvation, and they often enjoyed the freedom and independence that came with their new jobs.

Treasury girls were criticized for the work they performed outside the domestic sphere. Diarist Mary Boykin Chesnut was horrified by the notion of women working outside the home. She vowed never to submit to such degradation:

Survive or perish – we will not go into one of the departments. We will not stand up all day and cut notes apart, ordered round by a department clerk. We will live at home with our families and starve in a body. Any homework we will do. Any menial service – under the shadow of our own rooftree. Department – never!

The Confederate Treasury Department was located in Richmond until April 1864, when Treasury Secretary Christopher Memminger moved the Treasury Department to Columbia, South Carolina, and hired new clerks to replace those who had remained behind in Richmond. However, the Department was forced to leave Columbia in a hurry – just before Union General William Tecumseh Sherman‘s troops took control of the city on February 17, 1865. The Treasury Girls returned to Richmond, which they also had to evacuate, just before Union General Ulysses S. Grant’s forces took the city on April 2, 1865.

Image: Former Customs House held the offices of the Confederate Treasury Department

Image: Former Customs House held the offices of the Confederate Treasury Department

Richmond, Virginia

Many men returned from the war and reclaimed the jobs that had been filled by women, including clerkships like those held by the Union government girls and the Confederate treasury girls.

SOURCES

The Lady Clerks of the Treasury Department

Mr. Lincoln’s White House: The Treasury Building

U.S. Department of the Treasury: Treasury’s West Wing

The Numismatist, May 2010: Some Women Behind Our Money

Washington Post: Civil War gave birth to much of modern federal government

U.S. Department of the Treasury: Treasury spearheads hiring initiatives during the Civil War